Editor's note: This article, originally posted for the May 2016 Mercury Transit, has been updated for the Nov. 11, 2019 transit of Mercury.

This Monday (Nov. 11), Mercury will appear to cross in front of the disk of the sun, and will be visible as a tiny black dot against the bright source of light.

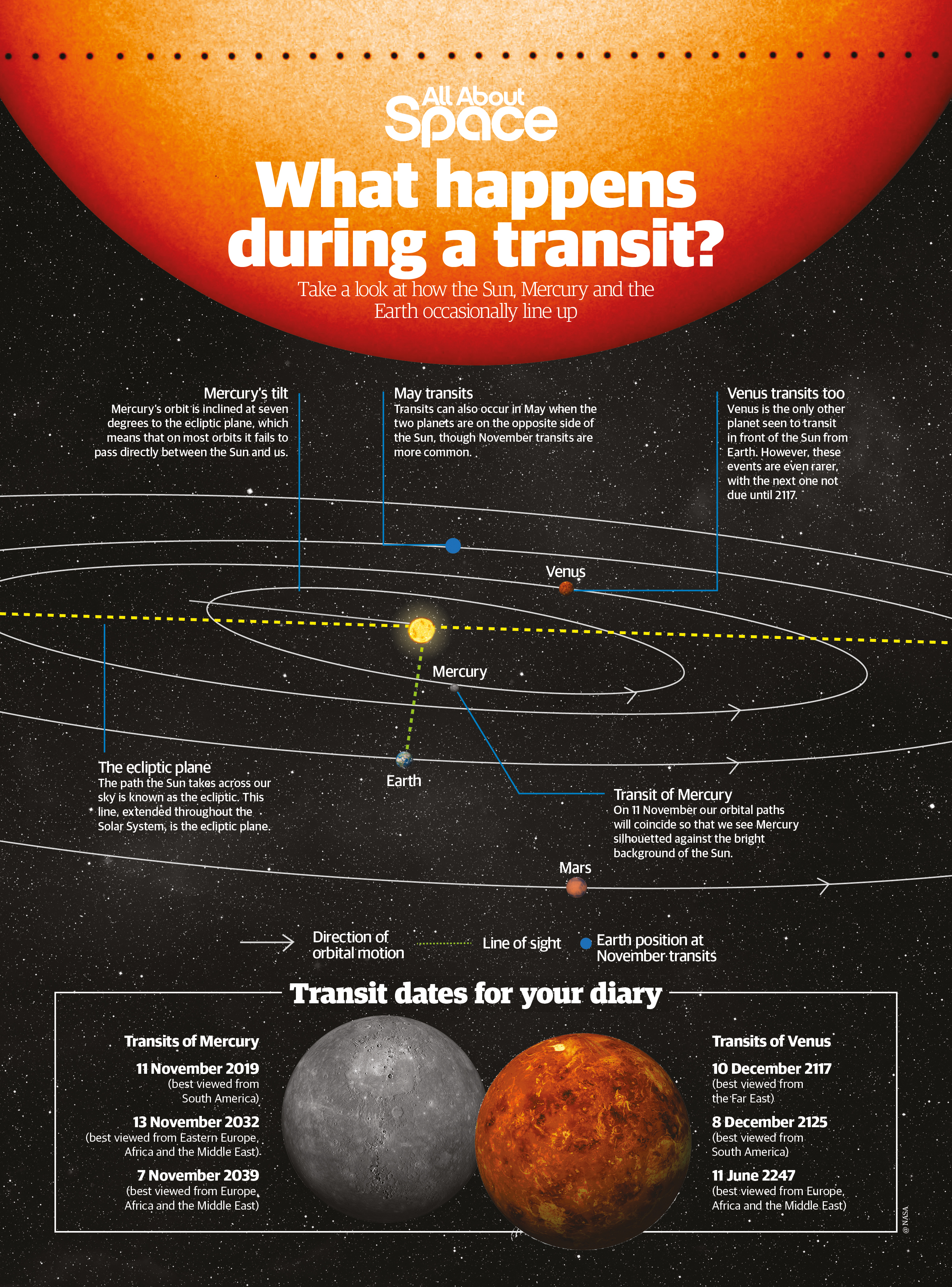

The event, which astronomers call a transit of Mercury, will occur only 14 times during the 21st century. As seen from Earth, only transits of Mercury and Venus are possible, because these are the only planets that lie between Earth and the sun. Transits of Venus occur in pairs separated by about eight years, with more than a century separating each pair.

Transits of Mercury and Venus hold an interesting place in astronomical history, mostly because of the slightly different times when the events occur as seen from different locations on the surface of the Earth. Astronomers noted that, for example, Mercury moved off the edge of the sun's disk at a different time when seen from one geographic location compared to another. This effect is called parallax, and it can be used in astronomy to measure distances.

- Mercury Transit 2019: Where and How to See It on Nov. 11

- How to Watch the Mercury Transit Live Online

- How to Find a Viewing Event Near You

Using parallax during the transits of Venus, astronomers were given the best opportunity available to measure the distance from the Earth to the sun — known as one astronomical unit. Kepler's third law showed that with this one measurement, it was possible to then measure the distance between the sun and other planets, based on how long it took each planet to go around the sun. The distance from the Earth to the sun was poorly known at that time. Astronomer Edmund Halley — of Halley's Comet fame — was the first to realize that transits could be used to measure the astronomical unit.

The transit technique relies on the precise measurement of the exact moment when Mercury or Venus began moving onto or off of the disk of the sun; two centuries ago, measuring those moments with high accuracy was difficult. Nonetheless, elaborate expeditions to observe the transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769 provided astronomers with their first good value for the astronomical unit. Since the 1960's, this method has been completely superseded by radar measurements of the distances to the other planets in the solar system.

Related: Here's Why Mercury Transits Are So Rare

Kepler predicted it, but Gassendi observed it

It was Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) who made the surprising discovery that, in 1631, both Mercury and Venus would transit the sun within less than a month of each other. Mercury would transit the sun on Nov. 7, followed by Venus on Dec. 6. The sight of a planet passing in front of the solar disk had never been seen before, so Kepler and his soon-to-be son-in-law, Jacob Bartsch, issued an "admonition" to all astronomers to be on the watch for these events. Because Kepler himself was uncertain about the exact circumstances (as he was concerned about the accuracy of his own tables), he urged prospective observers to carefully watch the sun a day early and, should nothing be seen, not give up until the day after.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Unfortunately, early November 1631 brought a very stormy and unsettled period of weather to much of Europe. So far, as historians know, only three individuals actually observed the transit of Mercury and only one, Pierre Gassendi (1592-1655), left a detailed account.

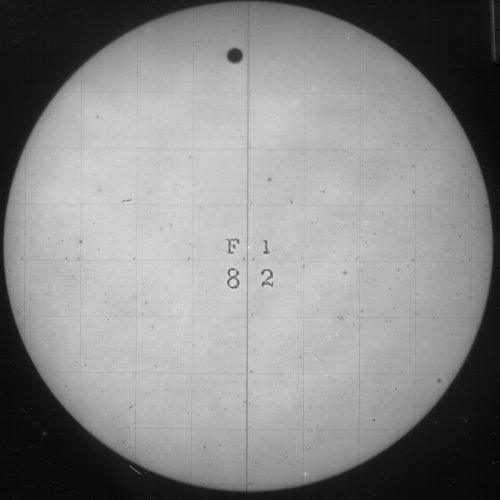

According to Gassendi's writings, he observed the transit from Paris, by means of projecting an 8-inch-wide (20 centimeters) image of the sun from his telescope's eyepiece onto a white screen. At around 9 a.m. local time on Nov. 7, through a scattered-to-broken layer of cloud cover, Gassendi anxiously watched the black dot of Mercury — which was much smaller than he had expected — as it slowly moved across the sun.

Unfortunately, Kepler did not live to witness this event; he died on Nov. 15, 1630, almost a year to the day before the Mercury transit. Despite his fears that his calculations might be off by a day or two, Kepler predicted the transit within 5 hours of it actually taking place — an astonishing feat for that time.

What to expect, and how to observe

Mercury Transit 2019: Here Are the Stages to Watch

Skywatchers must use special sun-viewing lenses to safely observe Mercury's transit.

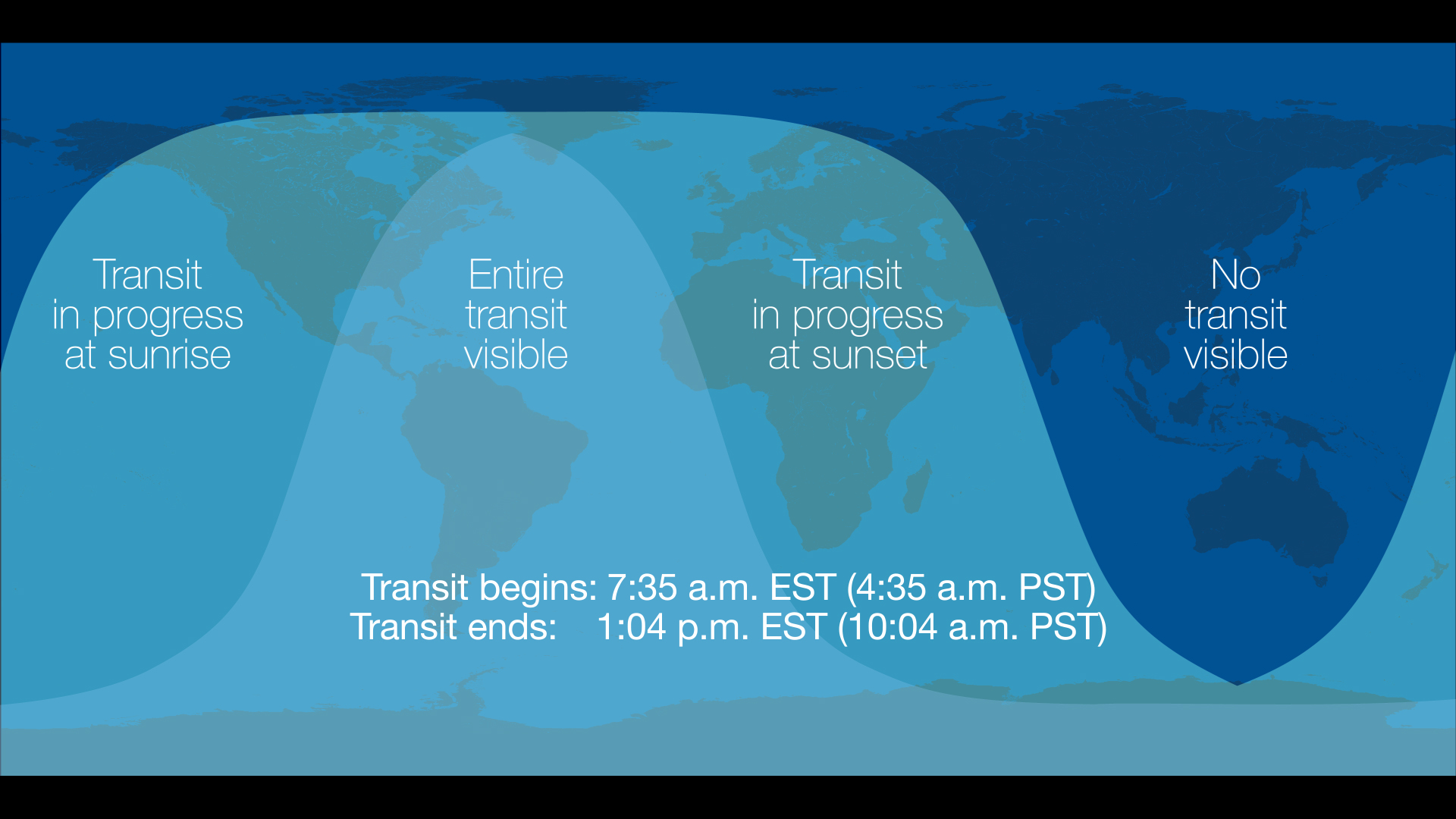

Here's what observers in the United States can expect for the 2019 transit of Mercury on Nov. 11.

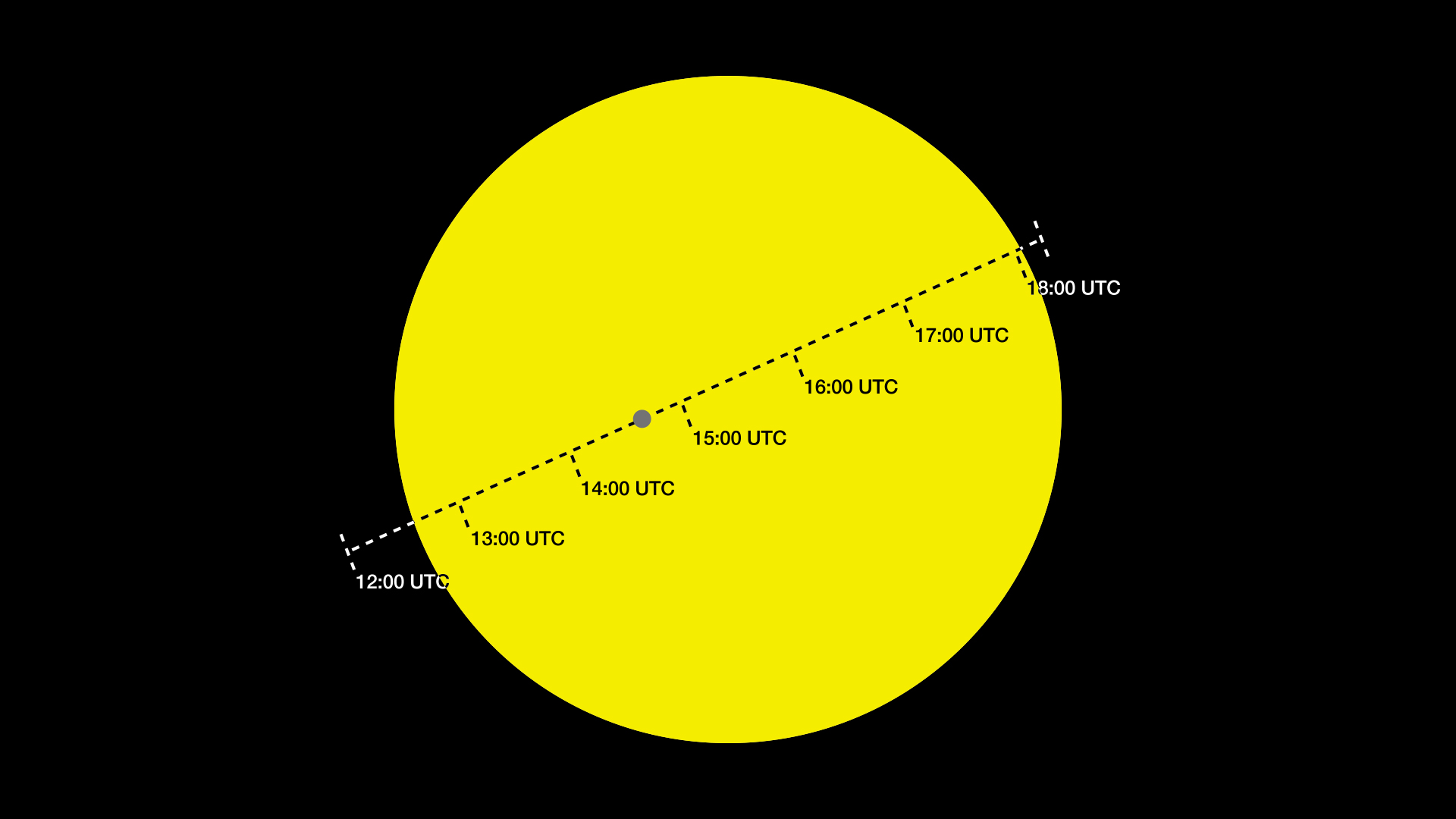

If you draw a line from roughly Lake Charles, Louisiana, to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, anywhere to the left (west) of that line, observers will see the black dot of Mercury on the rising sun. To the right (east) of that line, observers will be able to see the entire 5.5 hours of the transit from start to finish. Mercury will move into the left side of the disk of the sun at 7:35 a.m. EST (1212 GMT), and move to the right. The midpoint of the transit comes at 10:19 a.m. EST (1519 GMT), and Mercury will exit off the right side of the sun at 1:04 p.m. EST (1804 GMT).

Related: The Gear You Need to Safely Watch the Mercury Transit

More: How to Use Mobile Astronomy Apps to View the Mercury Transit of 2019

Skywatchers who have the proper equipment for observing sunspots will also be able to observe the transit of Mercury. (NOTE: Never look directly at the sun without protection. Doing so may result in serious eye damage or blindness. Scientists use special filters on telescopes to safely view the sun.)

The safest way to watch the transit event is to project the sun's image through a small telescope onto a white card or paper. This arrangement permits several observers to simultaneously view an enlarged solar image.

Based on observations made during previous Mercury transits, the planet can be readily perceived with a 2.4-inch or 3-inch refracting telescopes with 50x magnification, while at 150x, Mercury will appear as a round, black dot.

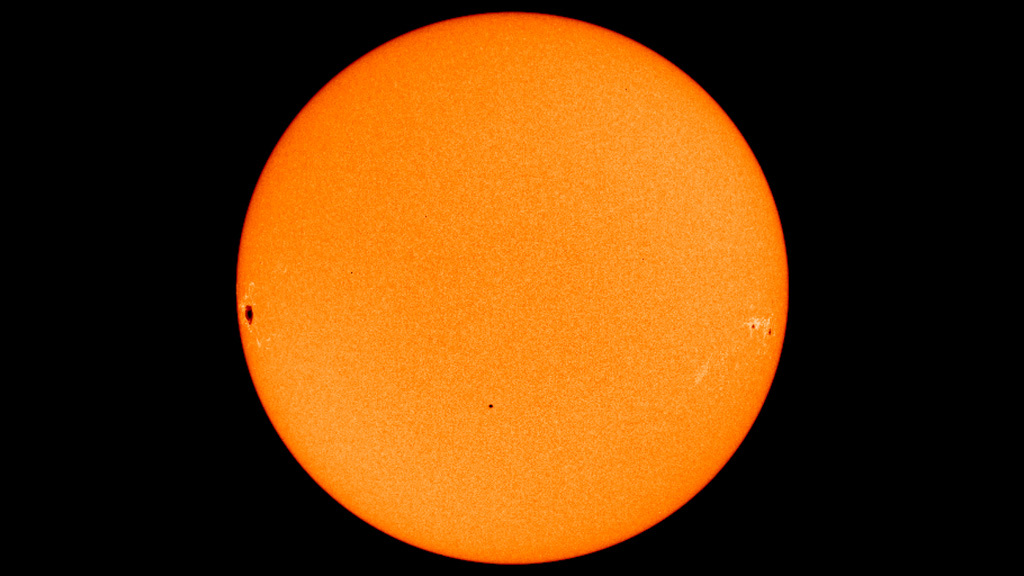

Reflecting telescopes can be similarly used, but with instruments that have larger than a 6-inch aperture, it's best to use a mask to reduce the aperture to 3-inches or less. Training a large reflecting telescope on the sun for long periods can cause a build-up of heat on the mirror or inside the tube, potentially damaging the instrument. Mercury should be readily recognizable as a tiny, sharp-edged dot, having only about 1/194th the sun's diameter. Through the transit, this dot will gradually crawl across the sun's face.

If there are any sunspots on the sun's disk, they will not appear quite as dark against the sun as the jet-black silhouette of Mercury.

Coming attractions

After Nov. 11, the next transits of Mercury will occur on Nov. 13, 2032 and Nov. 7, 2039. However, the Western Hemisphere will be turned away from the sun and in darkness when they occur, rendering both invisible for skywatchers in the Americas.

Not until May 7, 2049, will another Mercury transit be visible from North America!

So keep this in mind: Over the next 30 years, Americans will have only one chance to see Mercury pass across the disk of the sun and that lone opportunity comes this Monday morning, so don't miss it!

Here's to good luck and clear skies!

Editor's Note: Visit Space.com on Nov. 11 to see live webcast views of the rare Mercury transit as shown from telescopes on Earth and in space, along with complete coverage of the celestial event. If you SAFELY capture a photo of the transit of Mercury and would like to share it with Space.com and our news partners for a story or gallery, you can send images and comments in to spacephotos@space.com.

- Teach Your Kids About the Mercury Transit of 2019 with This NASA Guide

- How to Safely Observe the Sun (Infographic)

- Make a Safe Sun Projector with Binoculars (Video)

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. .

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.

-

rod I enjoyed this report and history in astronomy of observing Venus and Mercury transits. The graph showing time from ingress and egress is from left to right. Viewing in a refractor model telescope, the image will be upright but mirror reversed. Right to left :) Tomorrow for me looks party sunny, forecast was better a day or so ago but perhaps I may see some of the celestial event using my refractor telescope.Reply