Mercury Finishes Its Run Across the Sun

Citizen skywatchers, amateur astronomers and scientists alike looked skyward today (May 9) to see Mercury pass across the face of the sun, an event that will not happen again until 2019.

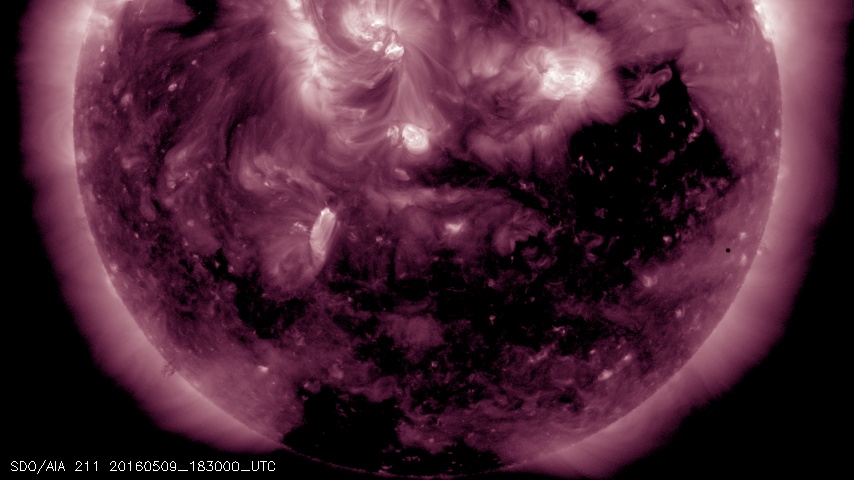

The solar system's smallest planet made a slow passage across the bright solar disc — an event that astronomers call a transit — starting at about 7:16 a.m. EDT (1116 GMT), according to NASA. The planet started on the left side of the sun's disk and took a downward path to the right. Mercury finally exited the sun’s disk at about 2:38 p.m. EDT (1838 GMT). The event was visible from all of North and South America, Europe, Africa, and much of Asia.

From the perspective of Earth, Mercury completes a transit of the sun about 13 times per century. The last transit was in 2006, and the next one will occur in 2019. In addition to being a fascinating event for skywatchers, this somewhat rare celestial event offers a lot of information for scientists. [The Mercury Transit of 2016 in Amazing Photos]

Today's transit of Mercury proved to be an extremely popular event with the general public and scientists alike. Live views of the event as well as programming about the science of the transit were broadcast online by both NASA and the European Space Association (ESA). NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory captured a slew of images of the tiny black spot moving across the massive, illuminated disk.

A live webcast from the Slooh Community Observatory featured views of the transit from observatories at multiple locations around the globe, including the Canary Islands; Prescott, Arizona; Hyères, France; and Las Vegas, Nevada.

Space.com readers sent in photos of the transit taken from Pennsylvania, Texas, New Jersey, Norway, India and Pakistan, among other places. You can see some of those reader photos in our 2016 Mercury transit image gallery.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It's all about perspective

"What happens during a transit is really all about perspective," said Jim Green, NASA's director of planetary science, during a live webcast today, in which NASA scientists discussed the science of the eclipse.

Mercury is the closest planet to the sun and orbits the star every 88 days, which means the planet technically passes "between" the Earth and the sun somewhat frequently. But a transit by Mercury happens only about 13 times every 100 years, because the orbits of the two planets are slightly misaligned. Mercury's orbit is titled by about 7 degrees relative to Earth's, Green said, which means the smaller planet "misses the sun, from our perspective, many, many times."

Images of the transit show Mercury as a very small, very circular black dot slowly moving at an angle across the brilliant surface of the sun. Looking directly at the sun can cause severe eye damage or blindness, so skywatchers must take safety precautions before viewing the star (look here to find out how to safely observe the sun).

One common method for observing the sun is with a pinhole camera, which projects an image of the sun onto a surface. Sunspots or transiting planets can usually be seen this way, but Mercury cannot.

The planet is too small to be seen transiting the sun without some kind of magnification. So it wasn't until the age of the telescope that humans first saw a transit of Mercury. A Mercury transit was recorded for the first time in 1631, by Pierre Gassendi, based on predictions made by Johannes Kepler.

The science of a transit

Humans have been observing transits of Mercury for nearly four centuries, but scientists still find new things to learn from each such event.

For example, during a transit, modern instruments can study Mercury's very thin atmosphere, also known as an exosphere. The body of the planet blocks the light from the sun, but as that light passes through the exosphere, the gases will block or absorb certain wavelengths of light. Mercury is expelling gases, including potassium and sodium, into its exosphere from under its surface.

Planets that transit their parent stars are of great interest to scientists hunting for worlds outside Earth's solar system. With the so-called transit method for hunting exoplanets, scientists studying distant stars can look for a dip in brightness caused by a planet passing in front of its star. Studying the transit of Mercury provides information about how small a transiting planet can be before it becomes impossible to see the object's effect on its star's brightness, NASA scientists said.

The next transit of Mercury will be visible in North and South America, but the following two transits (in 2032 and 2039) will not be visible in much of the Western Hemisphere. A Mercury transit will be visible to this part of the world once again in 2049.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter