Europe's Daring Mars Mission Prepares for Touchdown

Mars, we've got our eyes on you. Next week, a European spacecraft will make a challenging entry into the Martian atmosphere to deploy a lander on the surface. Called Schiaparelli, the little lander is expected to demonstrate future landing technologies while doing at least a few days of observations on Mars. This is the first half of a two-part mission; the second half of ExoMars will be composed of a sophisticated "biosignature"-hunting rover that will launch to the Red Planet in 2020. But first, the trailblazing Schiaparelli will lead the way, testing key technologies behind a successful landing on Mars. Here are some of the milestones during Schiaparelli's descent:

1) Separation

The first major milestone for the landing has already passed. Last week, the European Space Agency sent commands to Schiaparelli to prepare for it landing. Commands were sent up in two rounds -- hibernation wake-ups and science work on Oct. 3, and the command sequence for landing on Oct. 7. The goal is for Schiaparelli to work autonomously as it gets ready for landing; as it takes an average of 40 minutes' round trip to send commands between Earth and Mars, any lander must make it to the surface on its own.

RELATED: Europe's Next Mars Mission Spies Red Planet

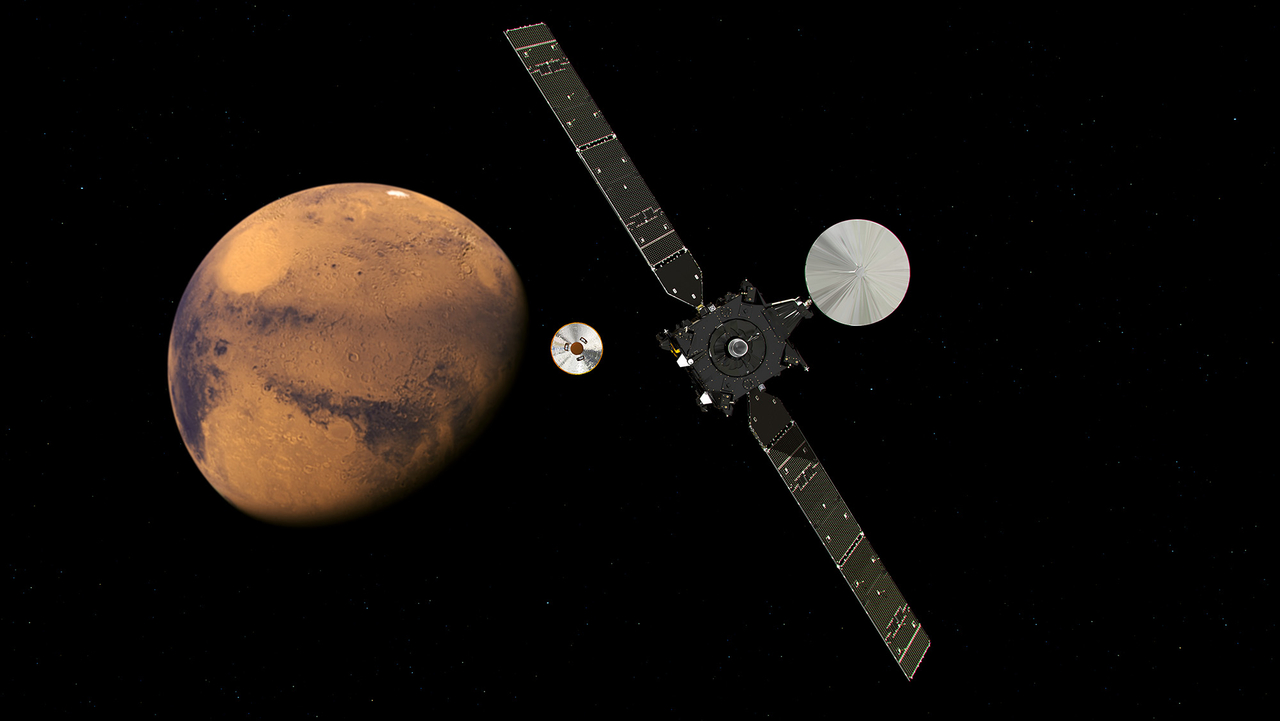

Schiaparelli has been riding on the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) for the past several months, but soon it will be time for each of the spacecraft to go their separate ways. On Oct. 16 (Sunday), Schiaparelli will separate from its carrier craft in preparation for the descent. On Oct. 19, Schiaparelli will make a descent to the surface while the TGO arrives in Mars orbit.

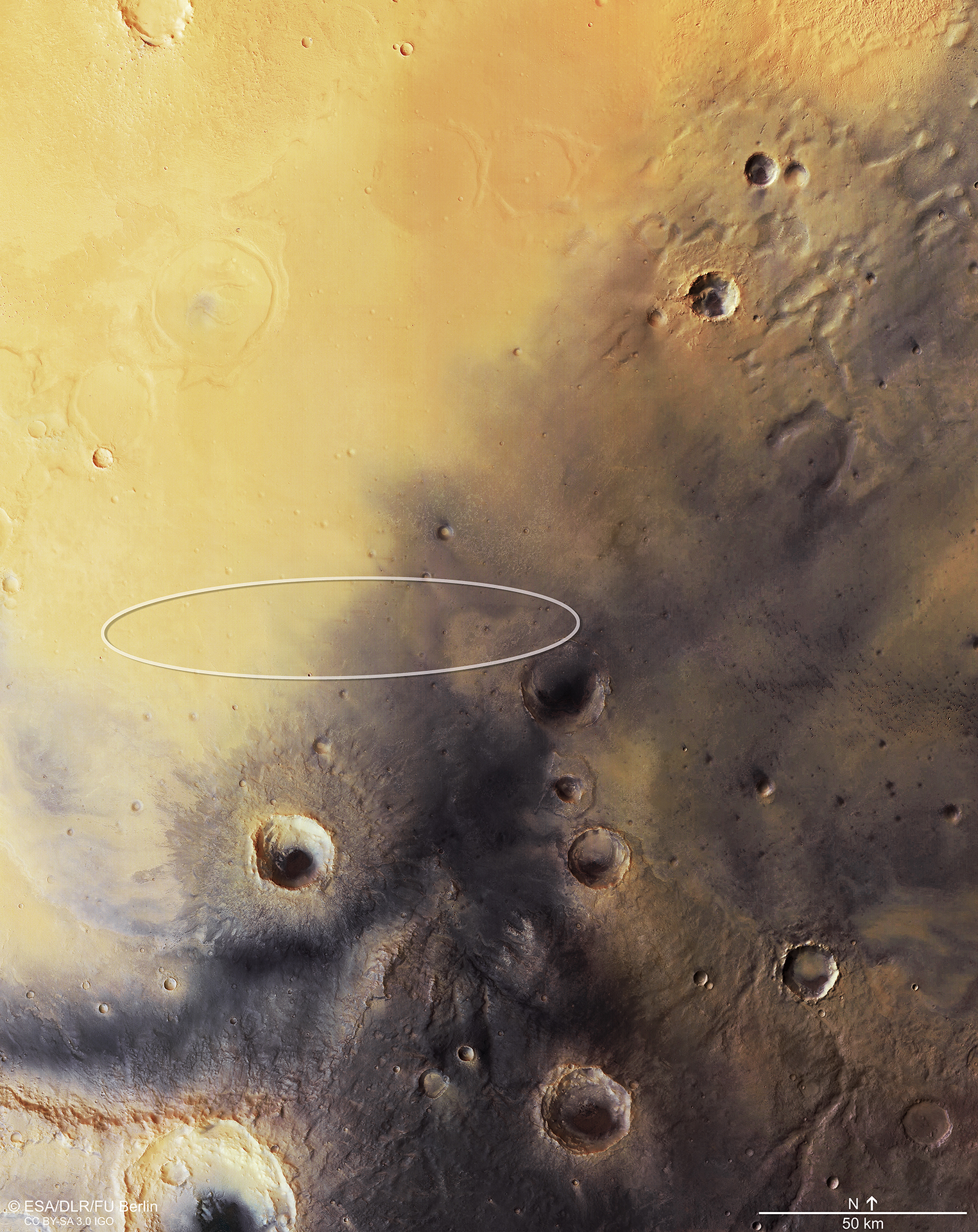

2) The Landing Zone

Once Schiaparelli leaves its host spacecraft, it will make a run at this landing site (circled) in Meridani Planum. The landing demonstrator is expected to land in a flat, smooth region just west of Endeavour crater, which NASA's Spirit opportunity rover is currently exploring. The region just to the south of Schiaparelli's landing site shows a number of grooved channels. The European Space Agency says they were likely carved by water. Also visible in the picture is Bopolu crater, a newer impact site within the much larger Miyamoto crater.

RELATED: Europe's Mars Life-Detection Mission Postponed

While Schiaparelli works below, the Trace Gas Orbiter will continue a separate mission to look at Martian atmospheric gases -- particularly methane, which could be a sign of geological or biological activity. Finding methane on Mars has been a historically difficult endeavor, with different spacecraft and telescopes measuring different abundances. Even the Curiosity rover spotted an increase int he gas, but the spike was not repeated at the same seasonal time as the mission continued into another Martian year.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

3) 13,000 mph to Zero in 6 Minutes

Schiaparelli will ride in a protective shell for most of the journey down to the surface. It's needed to protect delicate spacecraft components from the challenging entry -- traveling at 13,000 miles per hour! -- into the Martian atmosphere, which is thinner than Earth's but still thick enough to burn up a spacecraft riding down in the wrong orientation. As the spacecraft makes the descent, command sequences will have to work precisely to get the science package down safely for further observation. It will only take six minutes from entry into Mars' upper atmosphere to landing.

RELATED: Curiosity to Help Europe's ExoMars Zero-in on Mars Life

Mars has traditionally been a challenging planet for NASA, ESA and other agencies. In 2003, ESA attempted to send down the Beagle 2 lander on the Martian surface. The lander vanished from view and was not found again until high-resolution imagery of its site revealed the craft in 2015. The lander appeared intact, but its solar panels had only partially deployed.

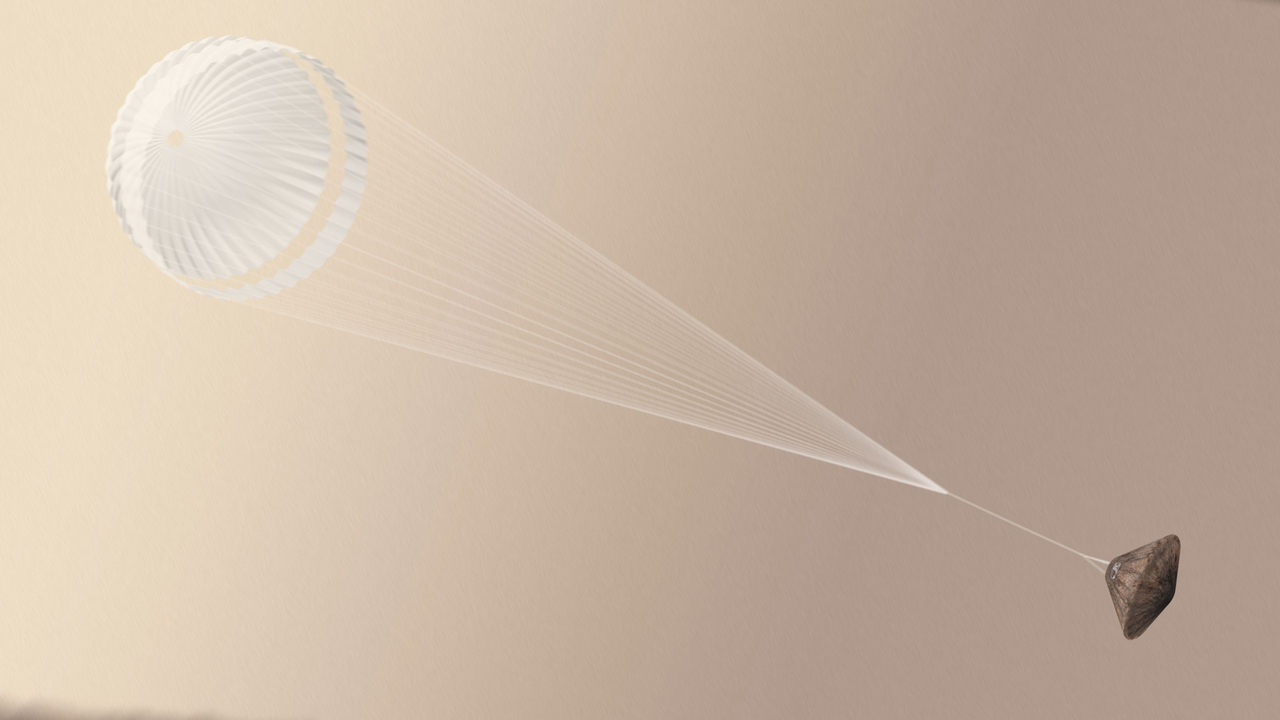

4) Parachute

Mars has a thin atmosphere, but it is thick enough to eventually slow down the Schiaparelli capsule as it falls to the surface. When Schiaparelli is about 11 kilometers (6.8 miles) from the surface and travelling at 1,700 km/h (1,056 mph), a parachute will pop out and slow its descent to a more reasonable 240 km/h (149 mph). At that point, the parachute will be jettisoned as Schiaparelli falls to the surface.

"The parachute is a 'disc-gap-band' type - the type that was used for the ESA Huygens probe descent to Titan [Saturn's moon] and for all NASA planetary entries so far," ESA wrote in a statement.

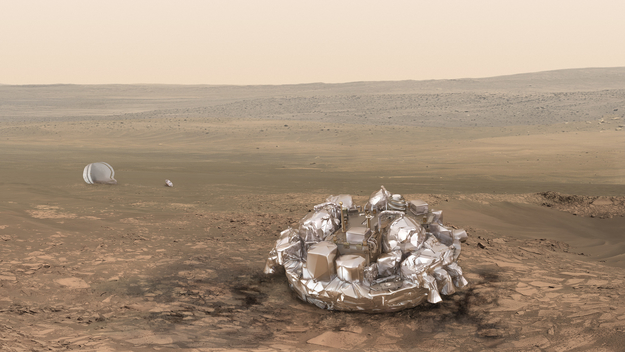

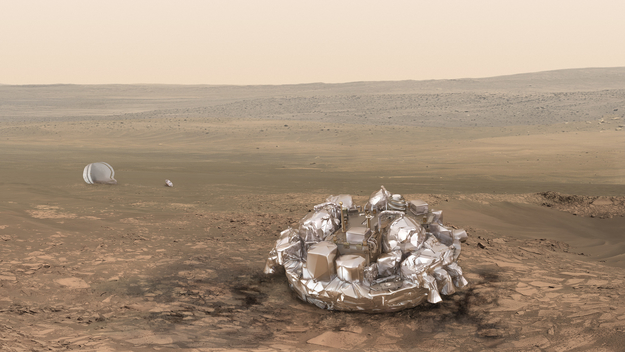

5) Touchdown

After losing the parachute, Schiaparelli will make a complicated descent to the surface. "Commands include ejecting the front and back aeroshells, operating the descent sensors, deploying the braking parachute and activating three groups of hydrazine thrusters to control its touchdown speed," ESA wrote in a statement. "A radar will measure Schiaparelli's height above the surface starting at about 7 km (4.3 miles). At around 2 m (6.5 feet), Schiaparelli will briefly hover before cutting its thrusters, leaving it to fall freely. A collapsible structure under the lander will absorb the shock of impact.

Schiaparelli represents just the beginning for ESA. The agency plans to send its first rover to the surface of Mars in the next phase of the ExoMars mission. Additionally, the technologies tested by Schiaparelli could be used in future missions. The lander is designed to operate for two days on the surface, but it could be longer.

"Schiaparelli also carries a small science package that will record the wind speed, humidity, pressure and temperature at its landing site, as well as obtain the first measurements of electric fields on the surface of Mars that may provide insight into how dust storms are triggered," ESA wrote in another statement.

Originally published on Discovery News.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.