Vast cosmic voids are far from empty — they're hiding something dark

You could swim through the deepest voids and encounter a single hydrogen atom in an entire football field's worth of space.

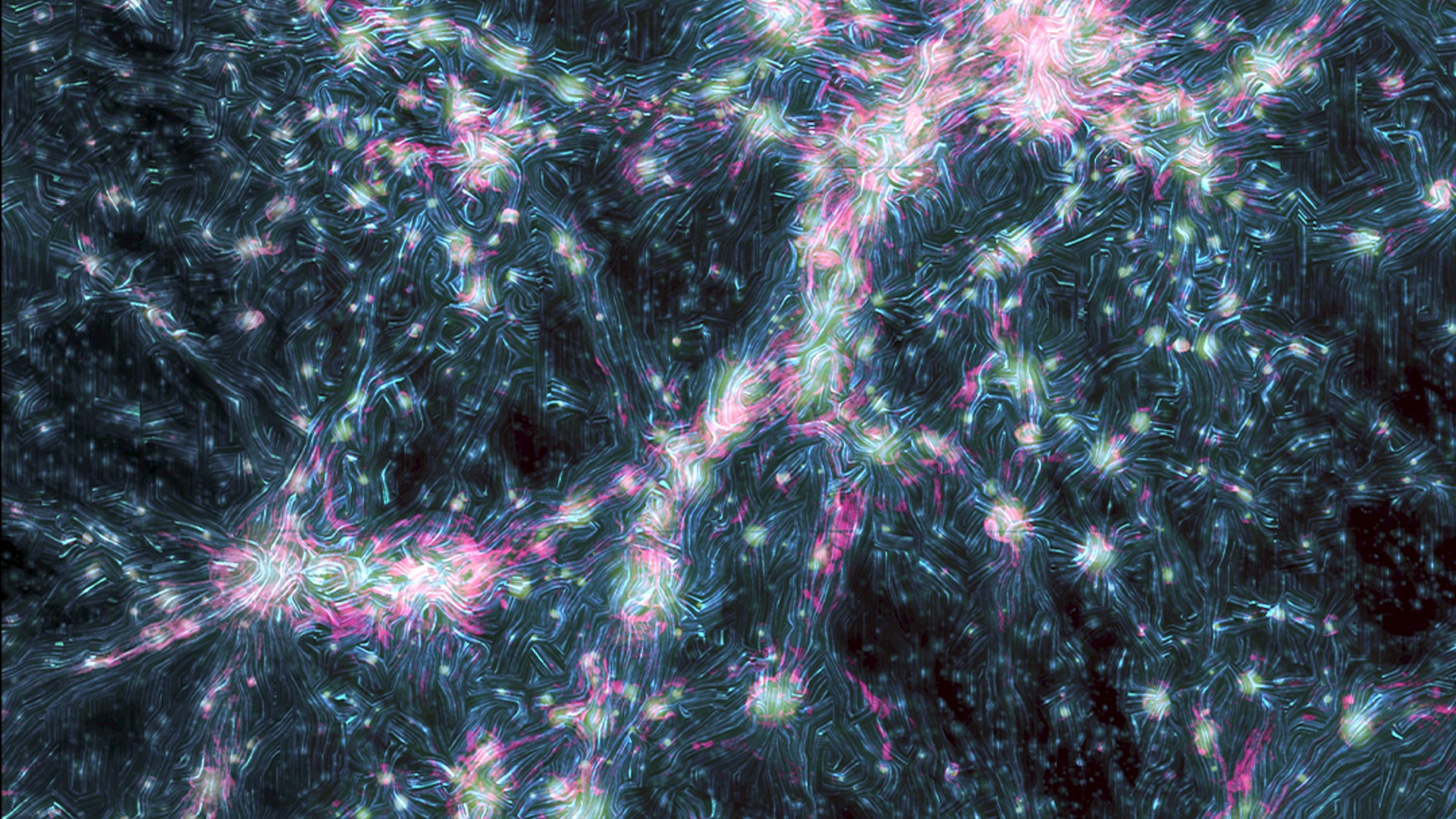

At the very largest scales, galaxies are not scattered around randomly. Instead, they form a pattern called the cosmic web. In fact, this is the largest pattern found in nature, with galaxies clumping together to form clusters, stringing themselves along filaments that stretch tens of millions of light-years on a side, and extending along broad walls that separate vast regions of the universe from each other.

These are the cosmic voids. The smallest voids are about 20 million light-years across on a side, and the largest ones go for hundreds of millions of light-years. They are the true cosmic deserts. But just like deserts on Earth, they're not entirely empty. So what's in these cosmic voids?

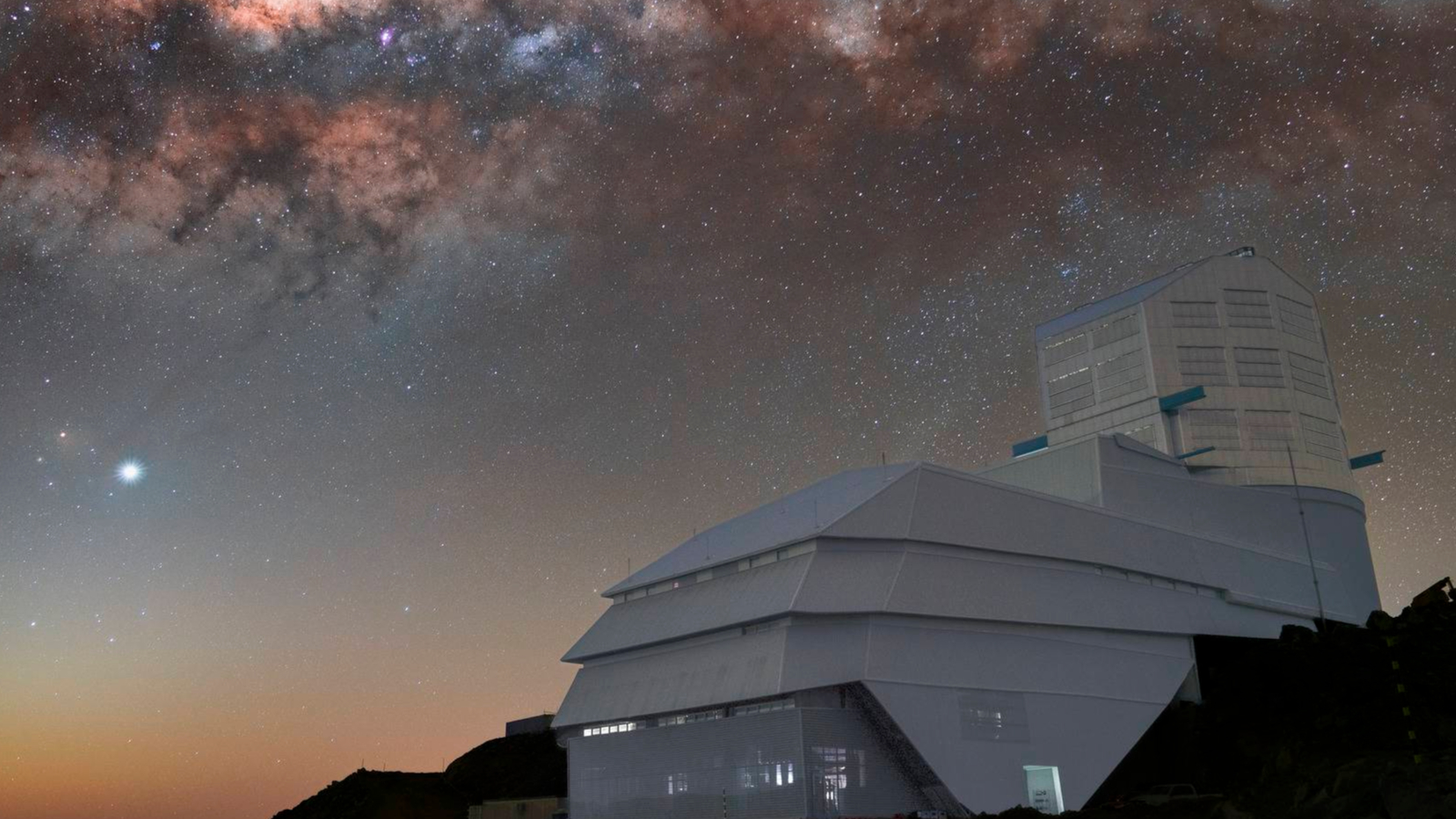

Within the voids, sophisticated observations can detect faint hints of structures, like small, dim dwarf galaxies dotting the vast expanses. Computer simulations reveal that there is even more to the story.

In addition to normal matter, there's dark matter. We can only see high-density clumps of dark matter because those have enough gravity to pull in normal matter that turns into stars and galaxies to illuminate our observations. And in the voids, there simply isn't enough density of dark matter, so nothing really lights up.

But computer simulations show that there are filaments and tendrils of dark matter crisscrossing the voids like a faint echo of the grand cosmic web, repeating itself in miniature.

Yet there are regions deep within the cosmic voids where not even dark matter penetrates. These are the lowest-density regions of the entire universe.

Still, if you work hard enough and are patient enough, you will detect an occasional bit of matter. The overall average density of the universe is roughly one hydrogen atom per cubic meter, and in the deepest corners of the voids, the average density is over 100 times less than that. So you could swim through the deepest voids and encounter a single hydrogen atom in, say, an entire football field's worth of space.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

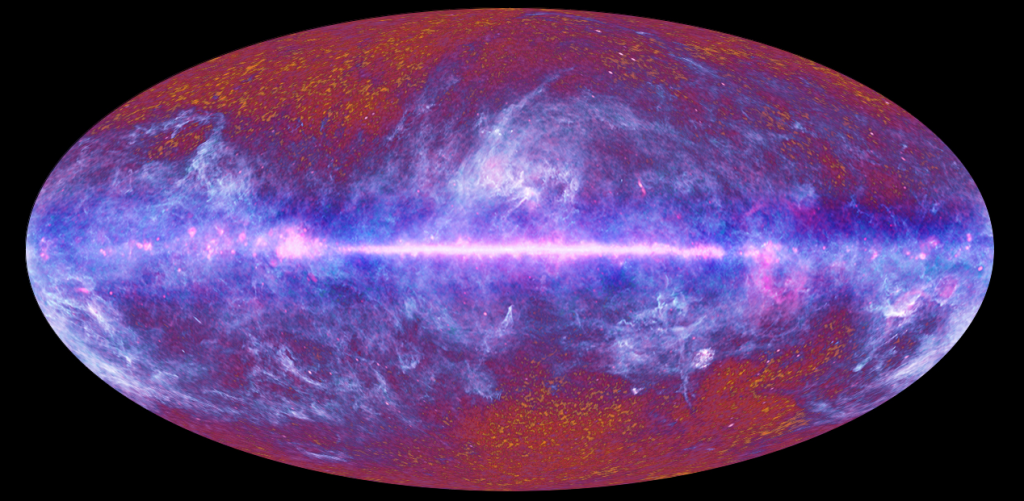

There is something else that fills up the voids: radiation. The cosmic microwave background — the leftover light from when the universe was only 380,000 years old — soaks the entire cosmos, filling every cubic centimeter. It makes up the vast majority of the radiation in the universe. No matter where you go, you can't escape the cosmic microwave background.

But that radiation is very old and very deeply redshifted into the microwave bands. It carries essentially no energy, so it barely counts.

That leaves one other component of the deepest parts of the voids. It's a very weak component, but it is a critical one for the universe: dark energy. Dark energy accounts for roughly 70% of the total energy density of the cosmos, but in most of the dense structures, like galaxies and clusters, you never know it's there.

Deep in the voids, however, dark energy takes over. It's the only thing left. This means that although the voids lack matter, they are filled to the brim with dark energy. And it's in the voids that dark energy is doing its work of tearing the universe apart.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.