Scientists find hints of the dark universe in 3D maps of the cosmos

A new way to study 3D maps of galaxies in the cosmos without compressing the data is revealing new information about the dark universe.

Hidden information in maps of galaxies spread across the universe could soon come forth, thanks to a new way of interrogating the data that preserves the three-dimensional nature of these maps.

The hidden information could be vital in telling us whether the standard model of cosmology is correct, or whether there are deviations from it that could affect our understanding of the "dark universe," which comprises dark matter and dark energy.

The research, led by astronomer Minh Nguyen of the University of Tokyo, utilizes powerful computer algorithms that are able to compare the relative positions of galaxies in a 3D map of the universe with detailed simulations that depict the growth and behavior of galaxies and haloes of dark matter.

Back in the old days, astronomers would conduct galaxy surveys by taking deep space images on photographic plates and then measuring directly on the plates, in two-dimensions, the spatial distribution of the galaxies. They'd try answering questions like "How close are these galaxies to their neighbors?" and "How well-aligned are they with one another?"

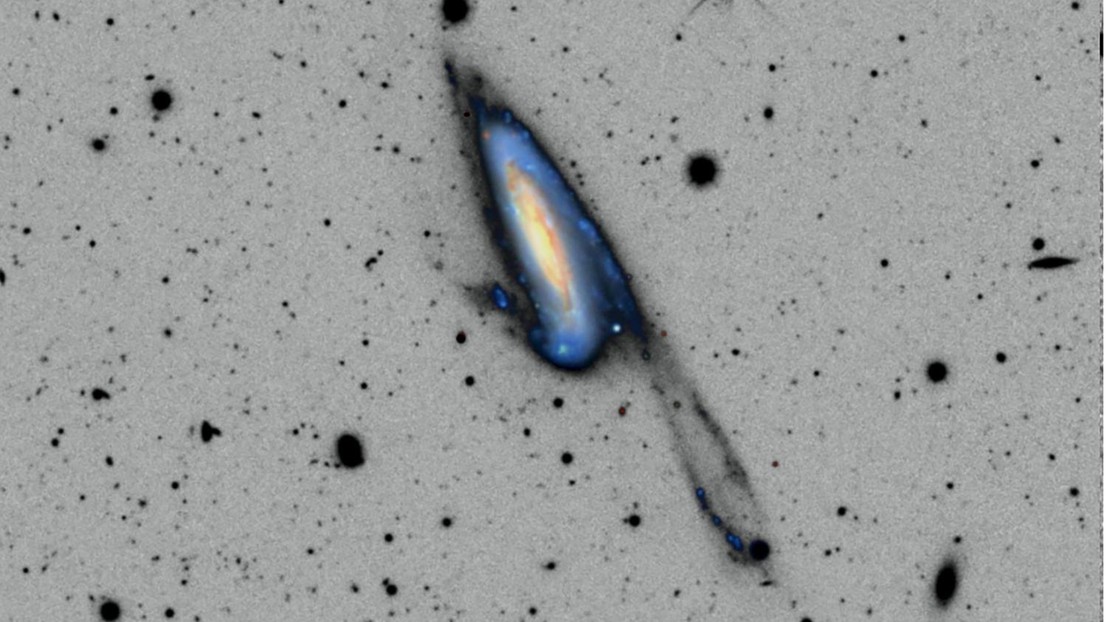

In modern times, a third dimension can be added to these surveys. It's all thanks to multi-object spectroscopy, which measures the redshift of these galaxies, and hence the distance to them in an expanding universe, in an observed volume of space. With such galactic distance measurements, it's actually possible to create a three-dimensional map of the universe.

However, the calculating power required to statistically analyze this three-dimensional galaxy data is fiendish, and so, for efficiency, the 3D data has traditionally been compressed down into what are called "n-point correlation functions," the "n" referring to a number (usually two or three points of data as mentioned above).

That's all well and good in most cases, but there has also been a nagging suspicion that compressing and analyzing the data this way results in information being missed — or hidden. And now, using a technique called "field-level inference" (FLI) in combination with a suite of algorithms in a framework called "LEFTfield" that models galaxy growth and clustering from the early universe to the present day, Nguyen's team has shown that vital information is indeed being suppressed by the compression. The team won third place in the Buchalter Cosmology Prize for this result.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"In field-level inference, we work directly with a 3D map of galaxies," Nguyen told Space.com. The map is represented on the computer by voxels, which are like three-dimensional pixels in a lattice grid. The FLI then depicts in this voxel lattice what it predicts the 3D structure of galaxies and underlying dark matter should look like according to the standard model of cosmology (which describes how large-scale structure in the universe evolves under the influence of dark matter and dark energy).

"With the help of powerful computer algorithms, FLI aims to match those predictions with the observed galaxy position at every point on the 3D lattice," said Nguyen.

N-point functions are popular because they speed up processing time and are more efficient to use, but today's algorithms are sophisticated enough to bridge the gap and enable the full, uncompressed data to be analyzed.

"Fortunately, there are modern computer algorithms that can speed up the exploration, or sampling, of this vast parameter space," said Nguyen.

Nguyen and his colleagues — Fabian Schmidt, Beatriz Tucci, Martin Reinecke and Andrija Kostić of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Germany — initially tested FLI on simulated maps of dark matter haloes, which are vast clouds of dark matter that surround galaxies and galaxy clusters. Think of the haloes as the scaffolding inside which visible matter assembles into galaxies. More recently, as part of "Beyond Two-Point Collaboration," Nguyen and Schmidt applied FLI on simulated galaxies as well, with the results soon to be published in The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.

Their results show a factor of between three and five improvement in detail and accuracy in the FLI analysis compared to two- and three-point correlation functions. This extra detail indicates that there is information that is being hidden in the old way of doing things.

And what can this hitherto hidden information tell us? Large-scale structures in the universe — the great chains of galaxy clusters that span the cosmos — can be traced back to the quantum fluctuations in the big bang that led to over-densities that grew under gravity into galaxies. FLI could reveal asymmetries in these fluctuations that have become frozen in time in the form of the distribution of galaxies, or how anomalies in the gravitational evolution of galaxies in the more recent universe could reveal details about dark matter, or in fact gravity itself.

In addition, "By having access to the entire underlying field of dark matter associated with the observed galaxy field, we might be more sensitive to local effects," said Nguyen. "Such local effects are averaged-over in analyses using n-point functions."

The next step is to put FLI to the test with real data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument at Kitt Peak National Observatory, the Subaru Prime Focus Spectrograph and the European Space Agency's Euclid mission, and in the future the Vera C. Rubin Observatory that should see first light later this year in Chile, as well as the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope that's set to launch in 2027. All will conduct redshift surveys of galaxies to assemble vast 3D maps of galactic distribution.

When it comes to the dark universe and how it has affected the growth of galaxies in large-scale structures across the universe, there's still much that we're, well, in the dark about. But with FLI, it's possible to describe the dark-matter distribution associated with the galaxies in the map.

"That’s quite neat, given that we can’t observe dark matter directly, and is complementary to dark-matter maps constructed from gravitational lensing," said Fabian Schmidt.

Ultimately, galaxy mapping isn't just about pictorially describing the universe; it could ultimately plot the path towards revelations about the origins of everything that we see in the cosmos.

The research was published on Nov. 27, 2024 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

-

Maxmeyes So scientists included in their models dark matter and dark energy, and when they run the models they can see dark matter and dark energy! Seems like circular reasoning. We have had Dark this and Dark that thrown at us for a decade with nothing to show for it or even a vague idea of how big this particle is, to the point where "Dark" is just a euphemism for "Give me research money" Most of the so-called theories have even broken the mass interaction and motion of galaxies problem that Dark Matter was invented to fix. When are they going to get serious about the legitimate alternatives to answer questions of celestial motion that don't require the invention of imaginary particles?Reply -

Helio If models drop DM and DE then astronomers would need to find another label to use to describe observed effects.Reply

The label,: dark matter", first came in 1933 to suggest extra matter would necessarily have to exist in the Coma cluster to explain the fast motions of the galaxies in order to maintain the cluster. But "extra ordinary claims require extra ordinary evidence" (Sagan). So, it stayed on the back burner.

Tons of evidence now demonstrate that DM is not due to observational errors.

DE wasn't hardly even imagined, but in the 1990s there was evidence from two independent sources showing the universe is accelerating. Such a force was envisioned first by Einstein when he added (later deleted) his cosmological constant. Lemaitre a few year later incorporated vacuum energy in his original expansion model (ie BBT). But little is known about what DE actually is, though there are a few dozen theories.

These are both mysteries but observations clearly show they are there.