Unknown physics may help dark energy act as 'antigravity' throughout the universe

"There are more questions than answers at this point."

Dark energy could have an accomplice that helps it slow the growth of large cosmic structures, such as vast superclusters made up of clusters of galaxies.

A new analysis of astronomical data suggests unknown physics is at work assisting dark energy in acting almost as "antigravity," undoing the work of gravity, which clumps together matter to build vast structures.

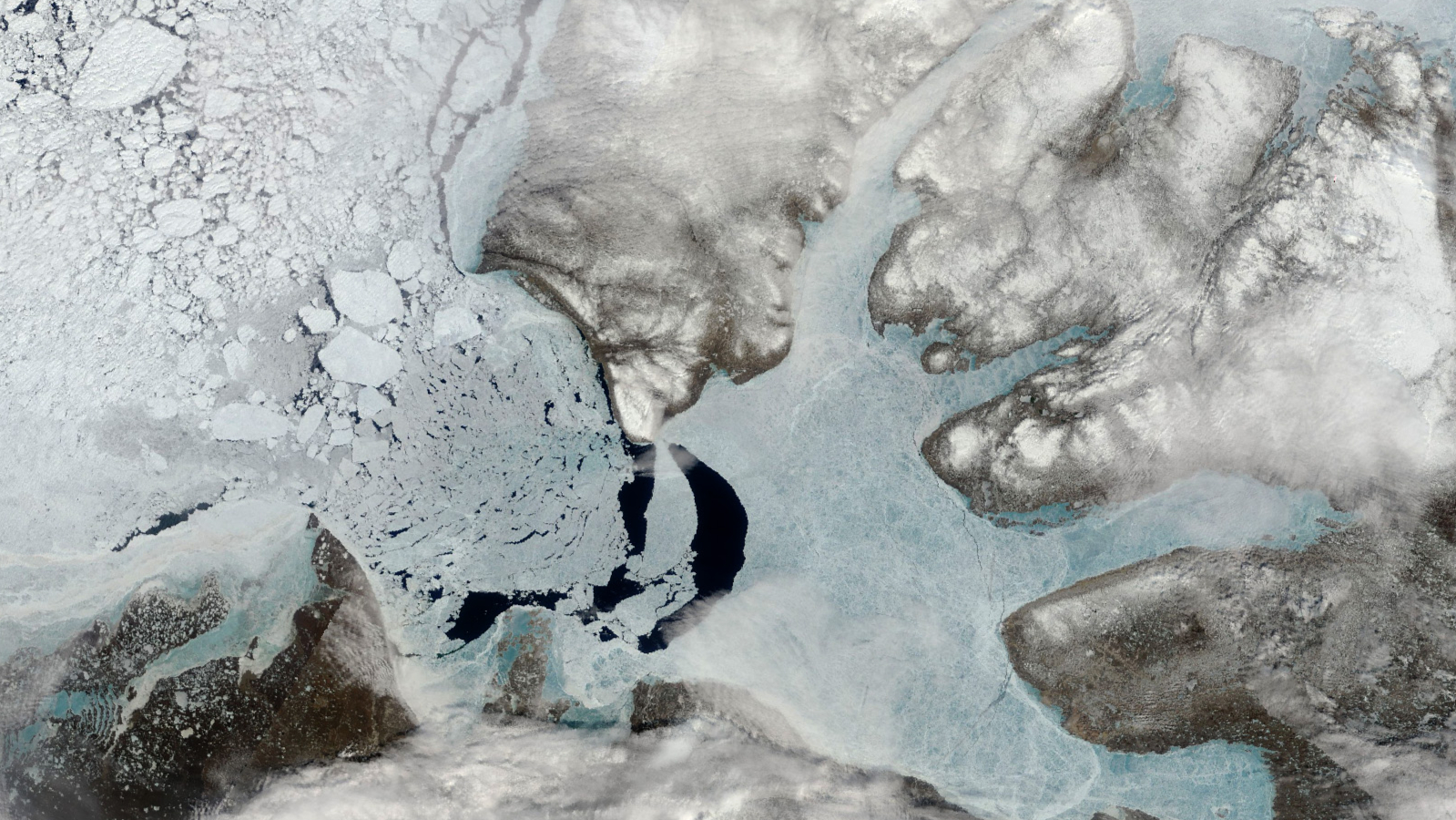

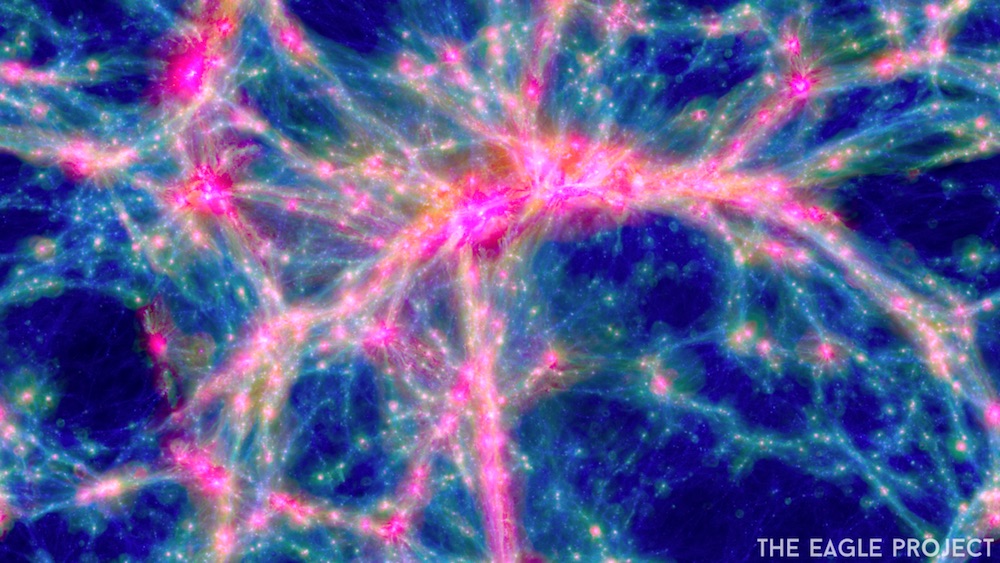

The large-scale structure of the universe refers to vast, interconnected patterns of galaxies, galaxy clusters, and superclusters organized into filaments, voids, and walls that comprise the "cosmic web."

Gravity has shaped this structure over billions of years. The team found that it is forming more slowly today compared to the rate at which it formed in the 13.8 billion-year-old universe's distant past.

Researchers discovered these hints at new physics using data from the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS).

BOSS maps the spatial distribution of luminous red galaxies (LRGs) and black hole-powered quasars to detect variations in matter in the early universe, or "baryon acoustic oscillations," which are "frozen into" a cosmic fossil called the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB).

"We found that structure formation in the late universe, as probed by galaxies in the BOSS survey, seems to be suppressed relative to expectations," team leader and Princeton University researcher Shi-Fan (Stephen) Chen told Space.com. "In fact, our results suggest that the suppression is quite independent of dark energy."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

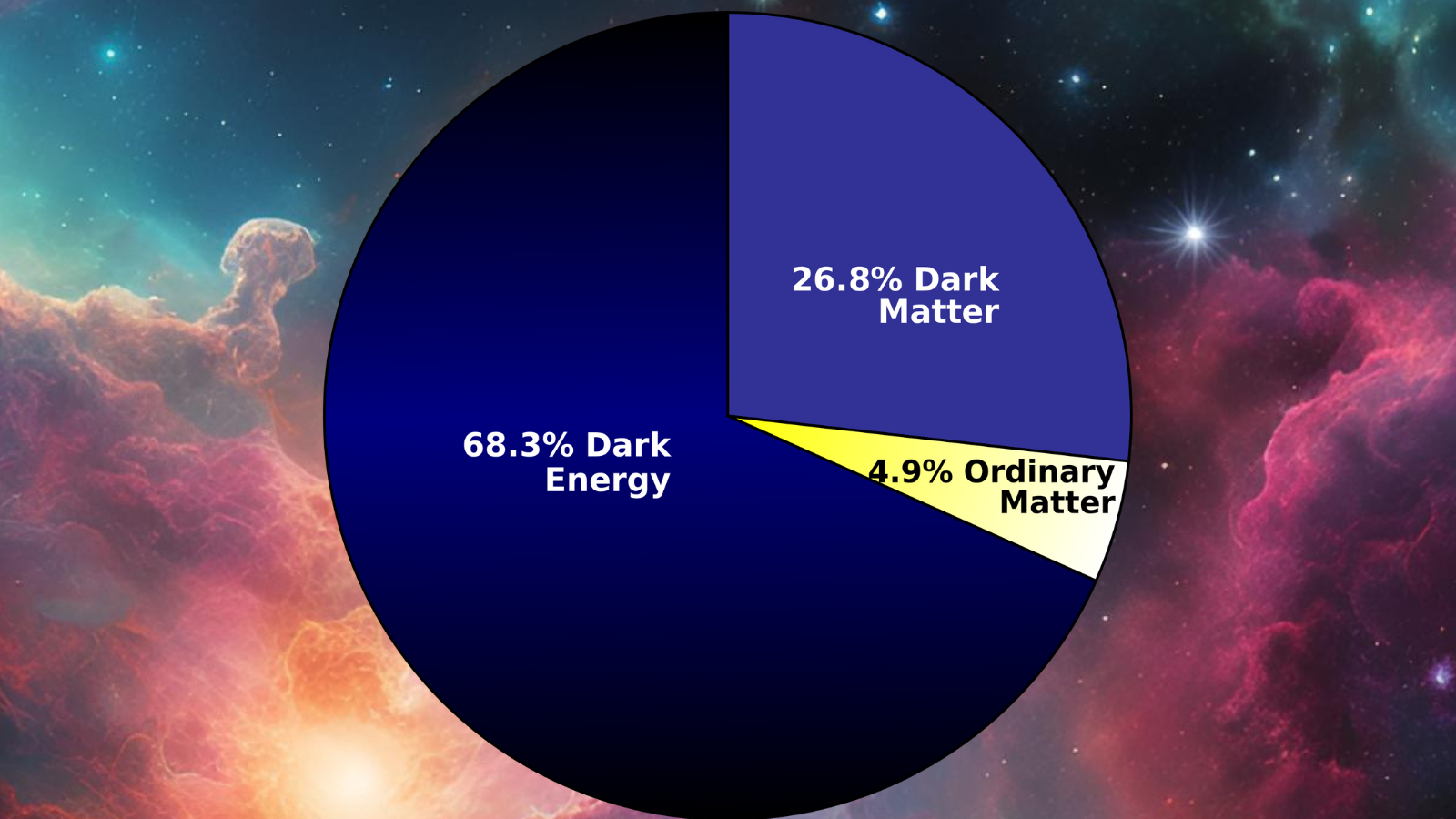

Why dark energy may not be acting alone

Dark energy is the placeholder name for whatever is accelerating the expansion of the universe. Discovered by two independent teams of astronomers in 1998, dark energy is thought to account for around 70% of the cosmos's total matter-energy budget.

The current "best explanation" for dark energy is the "cosmological constant" represented by the Greek letter lambda (Λ) in the so-called standard model of cosmology, also known as the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (ΛCDM) model.

The cosmological constant represents "vacuum energy," or the energy of empty space. This may sound very strange as it is connected to pairs of matter and antimatter particles popping in and out of existence. If a matter and antimatter particle pair is created with equal and opposite energy within a limited space, then the total energy of that space is still zero.

This is akin to the universe's overdraft facility, but rather than lending money, it lends energy. Just like a bank, however, the universe demands this energy to be paid back, which virtual particles do by annihilating each other.

This means that "empty space" can't ever really be guaranteed to be empty.

As crazy as the idea of matter appearing from nothing sounds, we've verified it experimentally. The Casimir effect, observed in labs across the globe, is a very famous example of virtual particles and the quantum fluctuations that create them and thus vacuum energy.

Here's the kicker: if dark energy is the cosmological constant, it should be exactly that, constant. So in the ΛCDM, even though dark energy causes a change in the rate at which the universe expands, the cosmological constant shouldn't change.

Recently, however, anomalies in results from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) caused a stir with cosmologists when they indicated that dark energy is changing over time. Thus, this changing or "dynamical dark energy" is contrary to ΛCDM.

"Recent results from DESI suggest that dark energy may not be a cosmological constant, but rather might evolve over time— we were curious to see if this tension with ΛCDM could be tied to the suppression of structure," Chen said.

If anything, checking DESI findings with data from BOSS has left the team with a larger mystery on their hands.

Dark energy and cosmological constant

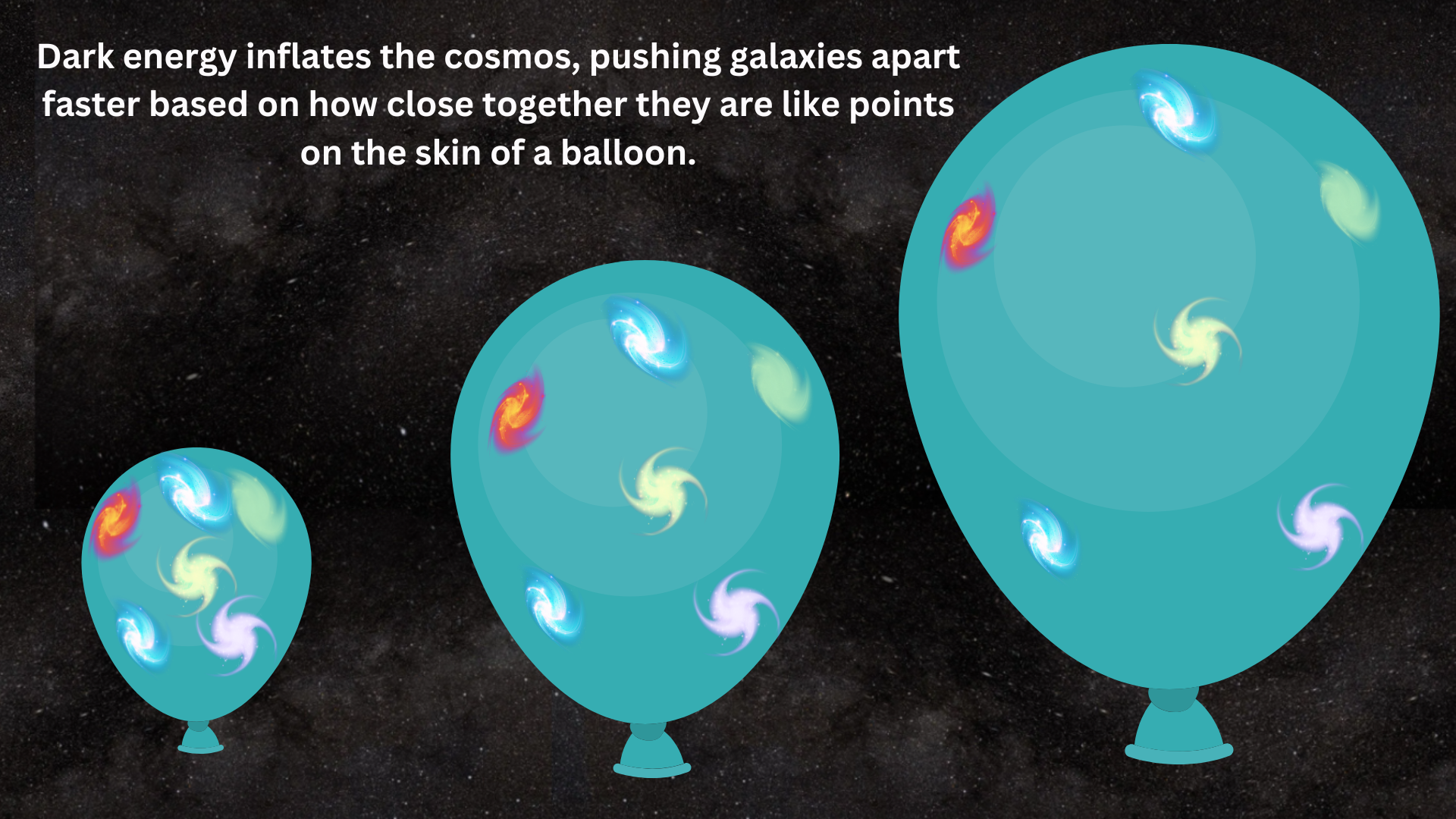

Whatever dark energy is, be it the cosmological constant or something else, the expansion of spacetime works on extremely large scales, so you won't see your coffee cup stretching away from you, and dark energy won't make your journey to work longer each morning (there is another excuse out of the window, sorry).

However, we can see distant galaxies moving away from us at ever-accelerating speeds. We can also see their effects in the BAO fluctuations frozen into the CMB because this fossil light from an event just after the Big Bang is almost evenly spread across the entire universe.

As such, it should come as no surprise that dark energy, as a force pushing apart galaxies, plays a role in stopping large-scale structures like galaxy clusters and superclusters from forming.

What is remarkable about the results obtained by Chen and colleagues is that they show that large-scale structures are even less common today than predicted by both the ΛCDM model of cosmology and when dark energy is allowed to vary. That implies something else, something new, is also at play, the identity of which is unknown.

"Many different theoretical explanations have been given for why the measured amplitude of cosmic structure at late times seems to come in slightly below expectations," Chen said. "At present, there are no conclusive answers."

However, there is one clue regarding the suppression of large-scale cosmic structures. This suppression seems to have kicked in around the same time dark energy came to dominate the universe.

When matter ruled the cosmos

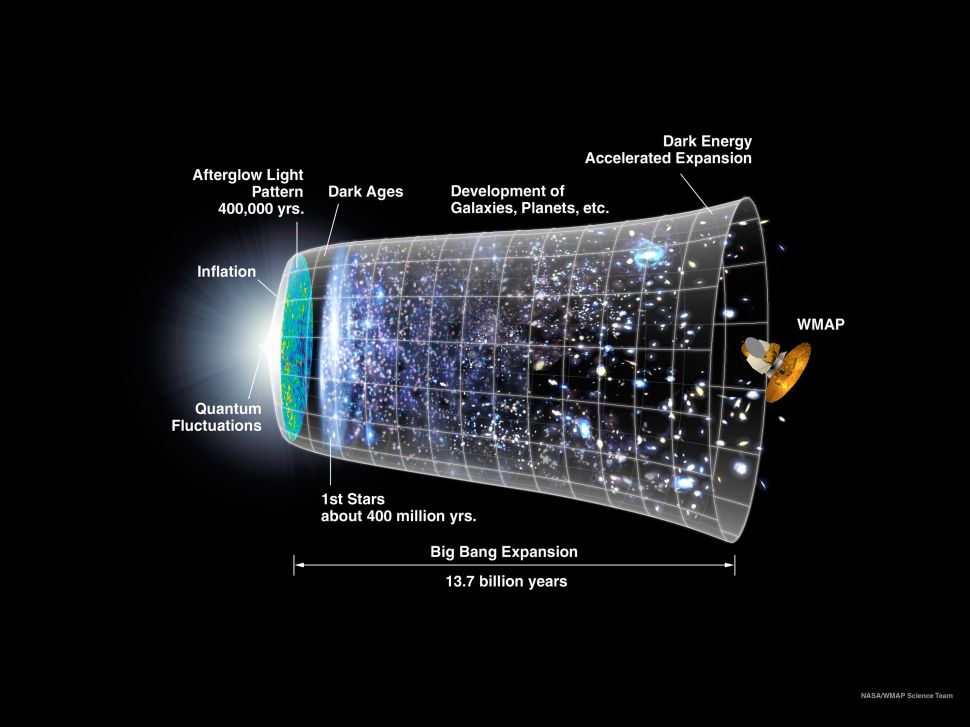

Dark energy may rule the universe now. But this wasn't always the way. Immediately after the Big Bang, the universe was dominated by radiation, driving its rapid inflation.

Around 70,000 years after the Big Bang, the universe had cooled enough to allow gravity to overwhelm radiation pressure. This slowed the initial Big Bang-driven expansion, bringing it to a near stop, and the first aggregates of matter, stars and galaxies were allowed to form.

At around 9 to 10 billion years after the Big Bang, or about 5 to 4 billion years ago, something strange began to happen. The universe started to expand again. Not only that, but this expansion began accelerating, and it is still accelerating today.

This is the beginning of the dark energy-dominated epoch; the problem is that no one knows how the switch from matter to dark energy domination happened.

"The BOSS data probes the universe when dark energy is beginning to kick in, and we think that this suppression cannot have occurred much earlier than that," Chen said.

So while dark energy seems linked to this suppression, this mysterious force still can't solely explain why the formation of large cosmic structures is slowed in the modern universe.

"When combining probes of the peculiar velocities of these galaxies, known as redshift-space distortions, and their cross correlation with the weak lensing of the CMB, we find that the probability of our results occurring due to random chance is 1 in 300,000," Chen said. "That suggests either that there's some unknown physics at work or that there's some unknown systematic error in the BOSS data."

The researcher added that with better data on the horizon, including the first public data on galaxy clustering from DESI released last week, the team will re-apply their methods, compare their results with their current findings, and detect any statistically significant differences.

"I think there are more questions than answers at this point," Chen said. "This research certainly enforces the idea that different cosmological datasets are beginning to be in tension when interpreted within the standard ΛCDM model of cosmology."

The team's research was published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.