Poor little Mercury is getting even smaller.

Astronomers have discovered a large valley on Mercury that provides further evidence for the planet's shrinkage — an odd phenomenon that has been the topic of debate for decades. NASA created a video overview of Mercury's 'Great Valley' here.

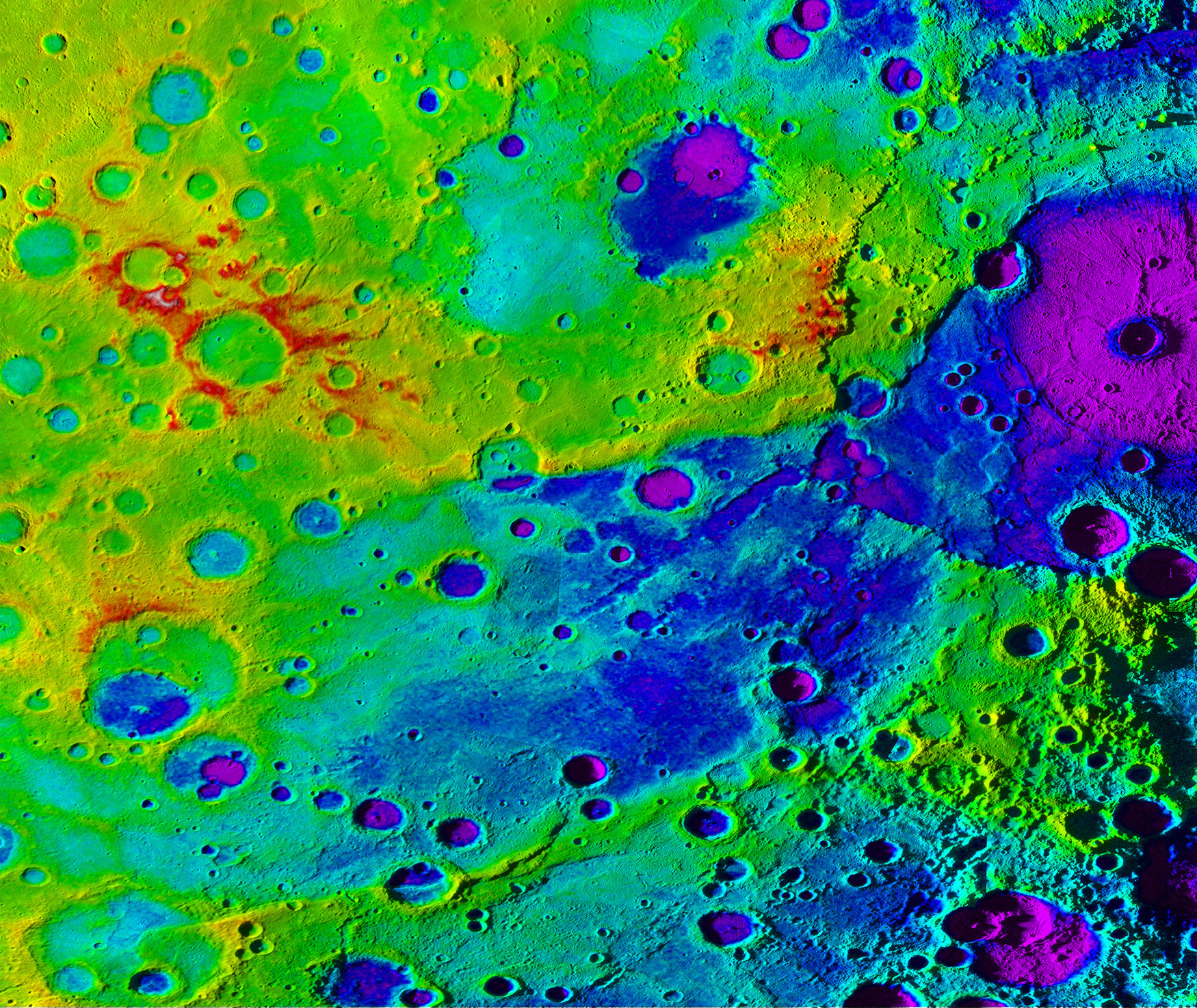

This newfound feature is about 620 miles long, 250 miles wide and 2 miles deep (1,000 by 400 by 3.2 kilometers), making it larger than Arizona's famous Grand Canyon and deeper than the Great Rift Valley in East Africa, scientists said. [10 Strange Facts About Mercury (A Photo Tour)]

"Unlike Earth's Great Rift Valley, Mercury's great valley is not caused by the pulling apart of lithospheric plates due to plate tectonics; it is the result of the global contraction of a shrinking one-plate planet," Tom Watters, a senior scientist at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., said in a statement.

Watters is lead author of a study published in Geophysical Research Letters that describes Mercury's great valley. He and his colleagues spotted the feature in images captured by NASA's MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft, which orbited the planet from March 2011 through April 2015.

Mercury is 3,032 miles (4,880 km) wide, and the vast majority of the planet's volume is taken up by its metallic core, which is estimated to be about 2,500 (4,000 km) wide. That core has been cooling slowly since Mercury (and the other planets) formed nearly 4.6 billion years ago, and the little world has been shrinking as a result.

The aforementioned debate involves the extent of that shrinkage. Observations by NASA's Mariner 10 spacecraft, which flew by Mercury three times in the mid-1970s, suggested that the planet has contracted by 1.2 to 2.5 miles (2 to 4 km) since its formation — significantly less than researchers' models had predicted.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But MESSENGER got a better look at Mercury, and its meticulous work allowed scientists to up the shrinkage estimate to 8.7 miles (14 km) or so. This higher number reconciled theory with observation.

As Watters noted, Mercury's crust is composed of a single plate (unlike Earth's, which consists primarily of seven large, interlocking plates). As Mercury has cooled, the rocks in this plate have been pushed together, thrusting some of them upward in cliff-like formations called scarps.

Two large, parallel scarps bound Mercury's great valley. But the valley's floor lies below the surrounding terrain, suggesting that the valley also formed via another process called "long-wavelength buckling," NASA officials said. Basically, the valley floor sagged downward as nearby rocks were pushed up.

"There are similar examples of this on Earth involving both oceanic and continental plates, but this may be the first evidence of this geological process on Mercury," Watters said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.