2017 Total Solar Eclipse: A Magnet for Scientists ... and Hordes of People

GRAPEVINE, Texas — The 2017 total solar eclipse, which will be visible across the contiguous United States, will be a scientific marvel and a potentially life-changing experience for people who view it. But experts warn that it will also be a logistical nightmare.

The eclipse was a hot topic of discussion Dec. 3 through Dec. 8 at the 229th meeting of the American Astronomical Society. One session at the meeting focused on some of the science that can be done only during an eclipse. During a plenary session talk, NASA heliophysicist C. Alex Young encouraged the scientists at the meeting to spread the word to people who might not be aware that the eclipse will be taking place in the U.S this year.

"Every single person that I've talked to [who has seen a total eclipse] has said it is a life-changing event," Young said during his plenary talk. "This is so much more than a scientific opportunity. This is a human event." ['Great American Total Solar Eclipse' of 2017: A Photo Guide]

But a panel of eclipse experts who spoke to members of the news media also warned that the eclipse will likely create a logistical nightmare. The areas of the country where the eclipse will reach totality (meaning the sun will be entirely covered by the moon) are expected to be congested with people trying to get a glimpse of the incredible sight. Federal agencies, including NASA, are bracing for the event.

A unique science event

It's a miraculous cosmic coincidence that the sun and moon appear to be almost the same size in Earth's sky. The size similarity of the two bodies means that during a total solar eclipse, the central body of the sun is blocked by the moon. When the eclipse reaches totality, it seems as though the world has suddenly changed from day to night, with a fast drop in temperature. With the light from the sun's main body obscured, it's possible for the naked eye to see the sun's corona, a region of intensely hot gas surrounding the main body that is typically overwhelmed by the light from the main body. To eclipse viewers, the corona appears as silvery streaks in the sky.

An instrument called a coronagraph is used to study the sun's corona (and to search for planets around distant stars), and it mimics the moon during a solar eclipse: A telescope or camera looks at the sun, and a coronagraph is placed over the central body of the sun to block the light. It's easy to see these coronagraphs at work in images taken by NASA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) and the Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) twin spacecraft.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And yet, humans can't make a coronagraph that gets as close to the edge of the sun as the moon does during an eclipse, Young said during his talk. (The reason for this has to do with "the optics" of the instruments, he said.) That means scientists can't see as much of the corona using those state-of-the-art instruments as they can during a natural eclipse. NASA has multiple experiments it will be supporting to collect data during the 2017 eclipse to take advantage of this opportunity.

Other safety concerns

The only time it is safe to look directly at the sun is during a total solar eclipse, during totality, when the central body is completely obscured. (Check out this Space.com infographic to learn more about how to view the sun safely.) In addition to eye-safety concerns around the event, Young told the media that federal agencies are concerned about safety in the region of totality.

"There's going to be traffic like we've never seen," Angela Speck, a professor of astronomy at the University of Columbia in Missouri and head of the AAS 2017 eclipse task force, at the media briefing.

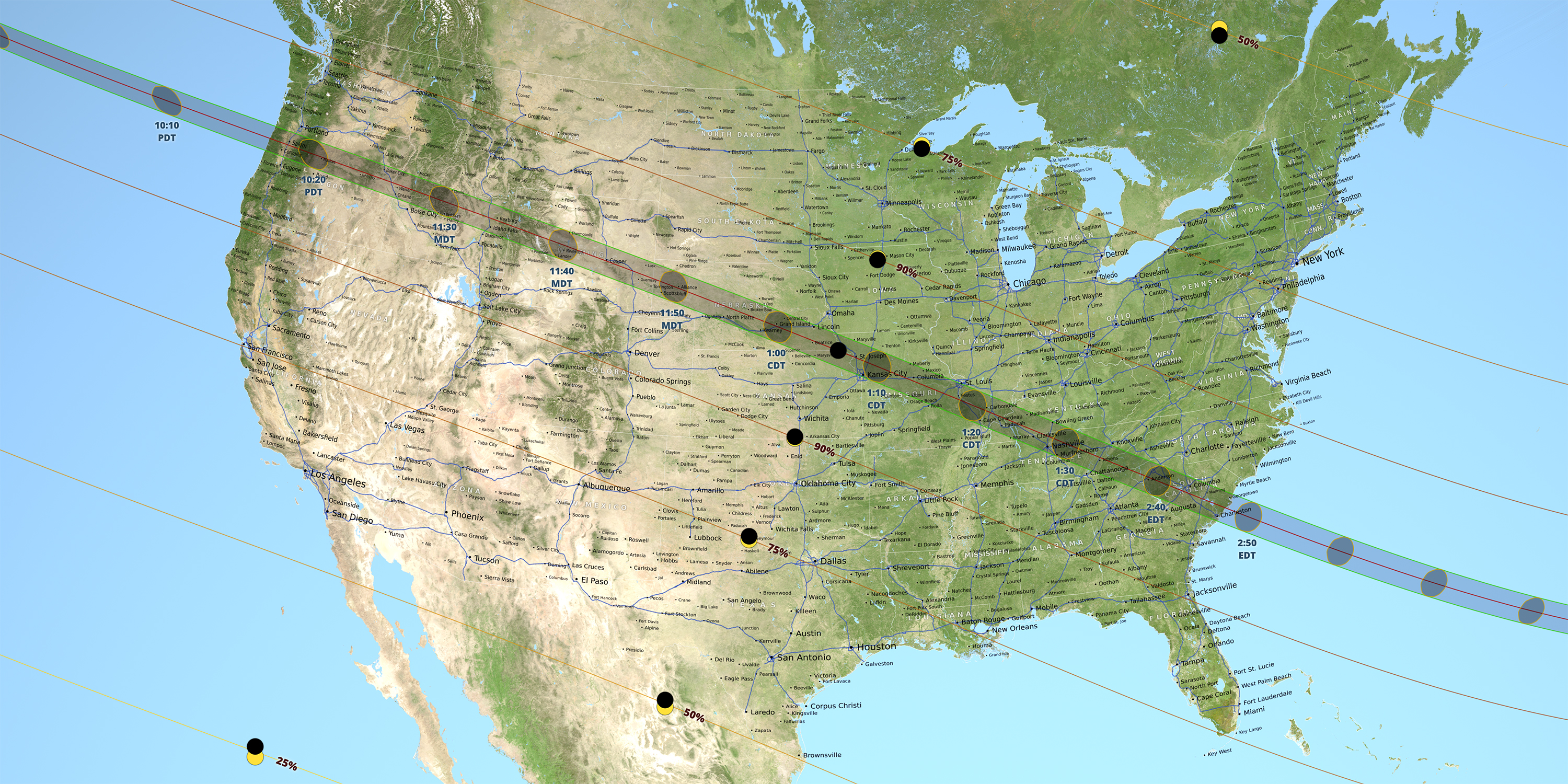

The eclipse's path of totality (the region where the total eclipse will be visible) extends from Oregon all the way to South Carolina, and is 70 miles wide (112 kilometers).

"Basically every single person in U.S. is within a long day's drive [of the path of totality], and there are 88 million people that live within 200 miles, which is a few hours' drive," she said.

If clouds appear over the path of totality as the eclipse approaches, people will most likely try to (quickly) drive to areas with clearer skies, which will create more traffic problems. And there are concerns that go along with any large crowd of people standing outside in the middle of summer: If people get heatstroke or become dehydrated, will there be emergency services available. Where will those people eat, and will there be restroom facilities? These are issues that Speck said her task force is trying to address.

Despite the logistical mayhem that will likely accompany the eclipse, Speck agreed with Young and said the science community should try to get the word out to members of the general public who may not know the event is happening.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Editor's Note: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that a coronagraph is in place on NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO).

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter