Venus Is About to Leave the Evening Sky: Here's What to Know

We are coming to the end of a spectacular evening showing by the planet Venus.

It seems hard to believe that this "sequined celestial showgirl" has been an evening object since June of last year. But during the summer and then on into the first half of the fall season, Venus remained low in the western twilight and set shortly after sundown. Unless you had a clear, unobstructed view toward the western horizon and looked right after sunset, you probably missed her. And then suddenly, right around Thanksgiving, Venus vaulted high into the sky and by Christmas was being noticed by practically everyone, appearing to hang like a bright holiday lantern above the western horizon.

From early December until now, Venus has been setting 3 hours or more after sunset and currently is still close to the pinnacle of her brightness, outshining the brightest nighttime star (Sirius) by nearly 20 times while casting faint, yet distinct shadows as seen from pitch-black locations. [Constellations and Planets: March 2017 Skywatching Video]

But by the end of this month, Venus will have, rather abruptly, left our evening sky, having made the transition during the final week of March from dusk to dawn visibility.

So, as the current evening apparition of Venus draws to a close and it moves into the morning sky, you might try to answer these questions by making your own observations: On what day will you last see Venus in the evening sky, at or after sunset, with the naked eye? With binoculars? When will you first see Venus in the morning, with and without an optical aid?

Perpetually in view

Later this month, Venus is going to do something out of the ordinary — remain in view right on through its conjunction with the sun. Normally, the planet becomes lost for a time in the solar glare as it sweeps between us and the sun. This time, however, the tilt of Venus' orbit (3.39 degrees different than that of Earth) will carry Venus widely north of the sun from our vantage point here on Earth.

So, for a few days around the time of Venus' "inferior conjunction," it will be possible to glimpse the planet both as an "evening star" low in the west after sunset and as a "morning star" in the east before sunup. Its slender crescent will measure nearly 1 arcsecond across — about 1/30 the apparent width of the moon and large enough to resolve with 7-power binoculars.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Seen from mid-northern latitudes, the ecliptic (the sun's apparent path through the sky) at this time of year is steeply inclined to the horizon in the early evening. Therefore, Venus descends rapidly, losing about 1.5 degrees each day during March. On March 23 at 3 a.m. EST (0800 GMT), the sun and Venus are in conjunction in "right ascension," with the planet 8.6 degrees due north of the center of the solar disk. (Reminder: Your closed fist held at arm's length is about 10 degrees wide.)

On the evening of March 22 and the morning of March 23, viewers in North America will see Venus about equally well in the evening and morning skies, almost 9 degrees to the upper right of the setting sun and about as far to the upper left of the rising sun. From latitude 40 degrees north, Venus will be 5 degrees above the horizon at sunrise and sunset.

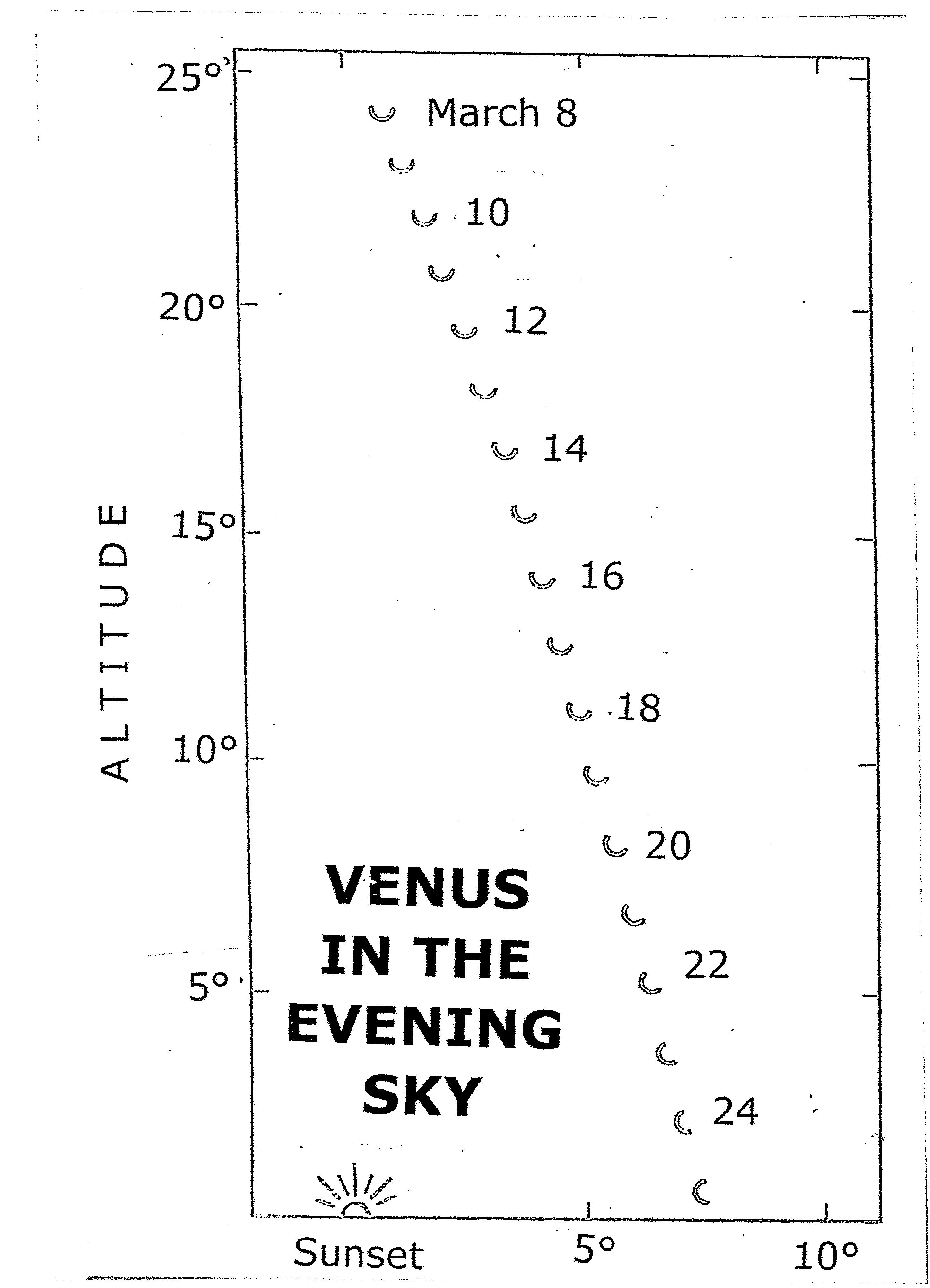

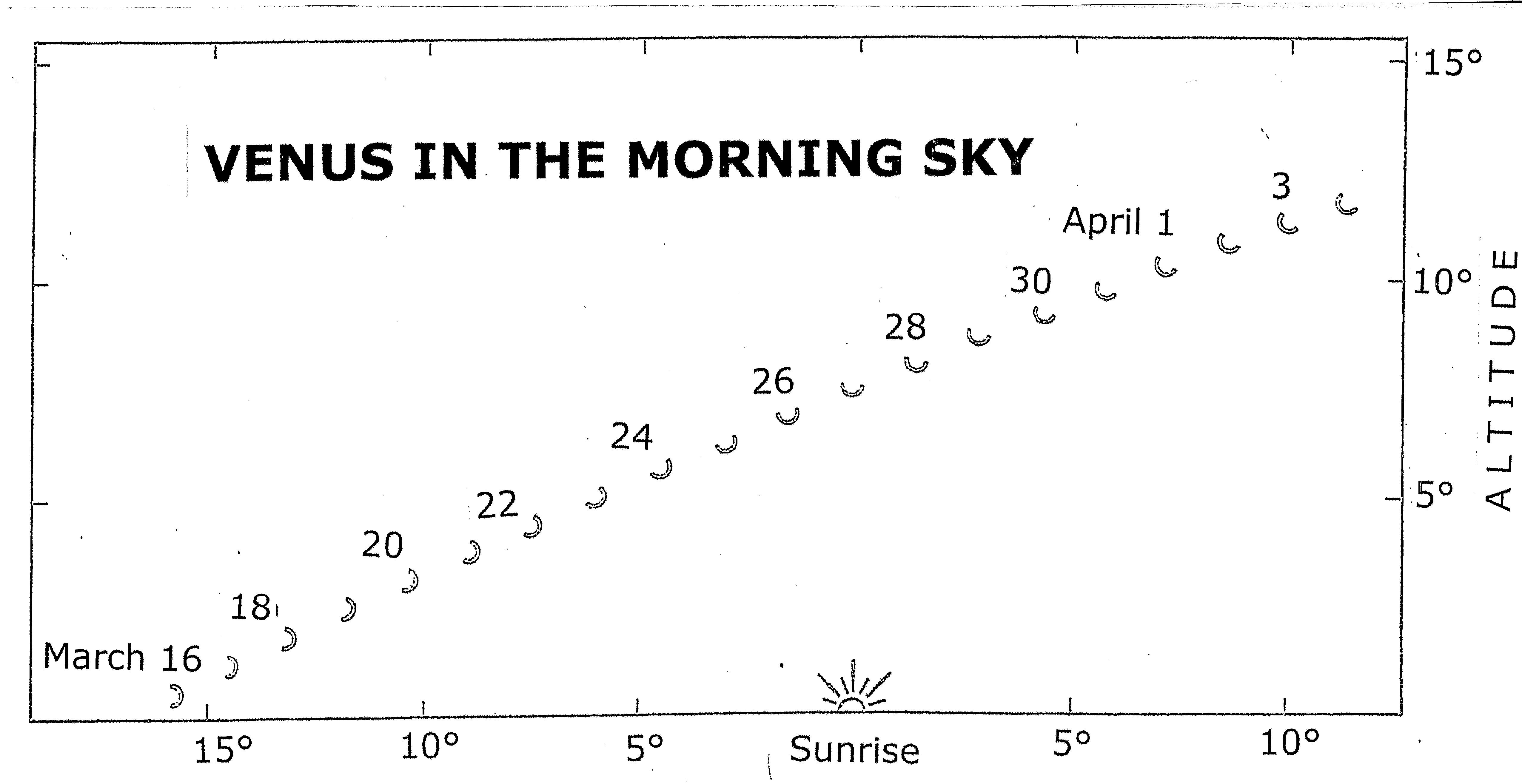

The two diagrams accompanying this story illustrate this effect. Plotted for a North American observer at a latitude of 40 degrees, they show that Venus will be 5 degrees above the horizon at sunset on March 22, yet equally high at sunrise the following morning! Shining at magnitude -4.1, the planet may be seen for a couple of days, centered on these dates, setting after the sun and rising the next morning before it.

From evening star to morning star

Venus passes inferior conjunction on March 25 at 5 a.m. EST (1000 GMT), when its celestial longitude (position along the ecliptic) is the same as that of the sun. Viewed from above the solar system, the planet would appear directly in line with the sun and Earth. Actually, Venus lies well north of the ecliptic plane at the time; we will see it 8.3 degrees north of the center of the sun's disk.

Although thinned to less than 1 percent of the planet's diameter, Venus' illuminated crescent will still be observable with only a slight optical aid. Using binoculars, try to observe Venus immediately after the sun goes down on March 24, by scanning the horizon 7 degrees to the right of the sunset point and about 2 degrees higher.

WARNING: Make sure you don't accidentally aim the binoculars at the sun; permanent eye damage could result. [How to Safely Observe the Sun (Infographic)]

On March 25, Venus sets with the sun and thereafter will no longer be visible in the evening. On what date will it first be possible to find Venus as a "morning star?"

We can refer to a very similar inferior conjunction of Venus almost exactly eight years ago. In 2009, Venus could be first sighted (with binoculars) in the morning sky nearly five days before inferior conjunction! Any sighting by March 19 or March 20 of this year will equal that 2009 feat. However, the planet won't be an easy target. On March 20, it will be about 10 degrees to the left of the rising sun but only 4 degrees higher (seen from latitude 40 degrees north). The ecliptic makes a shallow angle with the morning horizon, so each day Venus gains only about 0.67 degrees in altitude.

From latitude 40 degrees north, Venus will come up ahead of the sun as early as March 15, and from more northerly locations even sooner. By March 27, Venus will stand almost 9 degrees directly above the rising sun, thereafter moving ever farther to the upper right in the dawn sky.

In Part 2 of this Venus skywatching guide, we'll discuss how you can try to safely sight the narrow crescent of Venus during the daytime, when it will appear closest to the sun.

Editor's note: If you capture an amazing photo of Venus or any other celestial sight and want to share it with Space.com for a story or gallery, please send images and comments in to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Fios1 News in Rye Brook, N.Y. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.