Can Plants Grow from Clippings on the Space Station? Student Project Will Find Out

What started out as an after-school science-club project is now an important experiment aboard the International Space Station.

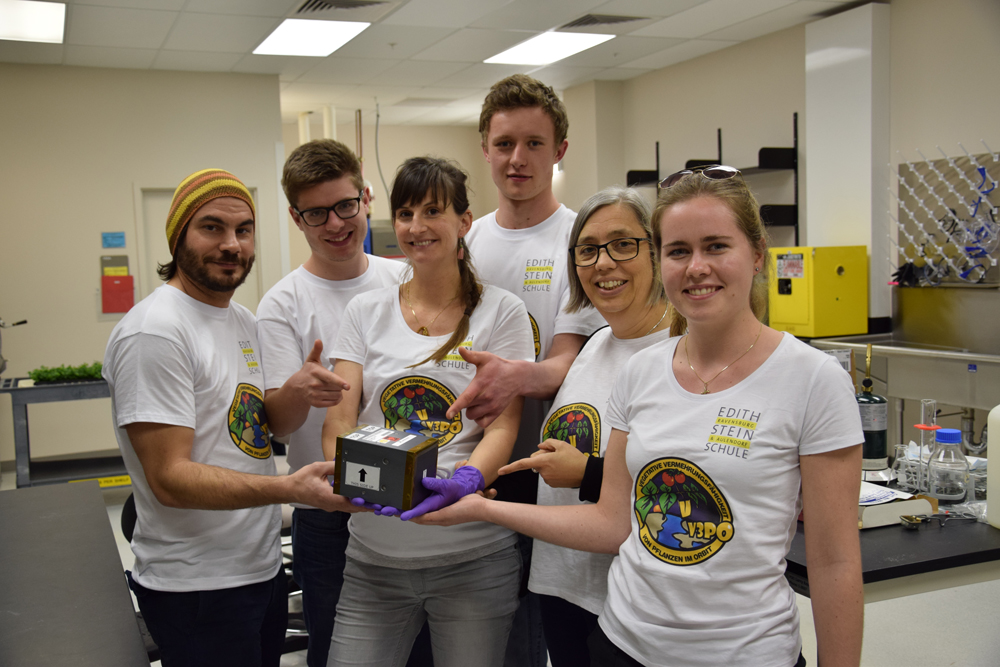

Astronauts have grown plants from seeds in microgravity before, but three students at the Edith-Stein School Ravensburg & Aulendorf in Germany wondered whether plants could also grow from cuttings. If proven possible, it would be a key development that would help astronauts quickly grow food in space. The students raised money through crowdfunding and industry sponsors to develop their experiment, called V3PO, to fly to the space station.

Maria Koch, Raphael Schilling and David Geray, who started the project about three years ago as 16-year-old students, traveled to Kennedy Space Center in Florida to watch the launch, which was delayed a day before finally lifting off Feb. 19. [Plants in Space: Photos by Gardening Astronauts]

The team was disappointed when the launch was called off with just 13 seconds to go, but were elated the next day when it finally flew, said Sebastian Rohrer, head of fungicide early biology at the German chemical company BASF's crop protection division and a scientific adviser to the students. "We kind of were staring at the skies and couldn't really believe it that it's now really happened," he told Space.com by phone from near the launch site.

"Everybody was standing there, mouths open, and didn't really know what to do, but then we started shaking hands and cheering — and from there, it kind of erupted," he added.

BASF was one of the major sponsors of the students' project, and the company also provided materials and equipment for the students to use.

On Feb. 23, the space station crew installed the NanoRacks module with the experiment, which activated lights and a video feed to document the plants' fate. The whole space-borne package will return to Earth along with SpaceX's Dragon spacecraft in about two weeks, and in the meantime monitoring images are sent down daily.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The V3PO team chose a small, decorative plant called Ficus pumila (commonly called the creeping fig) for the experiment. The plant is compact enough to fit in the two compartments of the tiny box sent to space; each compartment measures 1.6 by 1.2 by 1.8 inches (4 by 3 by 4.5 centimeters). It also can withstand the temperature changes inherent in a flight through space; the plants were cooled to 4 degrees Celsius (7.2 degrees Fahrenheit) beforehand to make sure they wouldn't grow until they were in microgravity. Four cuttings of the plant, along with a nutrient gel, were placed in each chamber.

When the experiment lands back on Earth, the students will re-create the atmospheric conditions the plants went through, to see how Earth-bound plants fare in the same circumstances, the students and teacher, Brigitte Schuermann, told Space.com by phone (through a translator).

On Earth, pieces cut from the plants' stems can shoot out their own roots and grow into new plants — a behavior that can be used to replicate crops such as tomatoes on Earth. If the little plant cuttings can grow roots without the help of gravity, they could pave the way for easier food growing on long trips through space, like those astronauts will experience when traveling to Mars someday, the students said.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.