'Asteroid Hunters' Look to Defend Earth: Q&A with Author Carrie Nugent

The solar system is much wilder and more chaotic than most people think, and vigilant scientists are all that stand between Earth and a catastrophic asteroid impact, according to a new book on the science of asteroid monitoring and tracking.

"Asteroid Hunters" (Simon & Schuster, 2017), released today (March 14), offers a quick but comprehensive view of what's happening in Earth's solar system, and highlights the many eyes on the sky determined to catalog and track every asteroid and near-Earth object that could potentially pose a threat. Plus, it details the different ways we could turn away an unwanted solar system visitor streaming toward Earth.

Space.com talked with "Asteroid Hunters" author Carrie Nugent, a researcher who works with NASA's asteroid-hunting space telescope NEOWISE (Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer), about the threat of an asteroid impact, how we find them and what we would do if one came knocking. [Near-Earth Asteroids: Famous Space Rock Flybys and Close Calls (Infographic)]

Space.com: What should people know about asteroid monitoring?

Carrie Nugent: We're at a very unique point in human history where we have the capability, for the very first time, to really chart our cosmic neighborhood — the region of space that's closest to Earth — [and] find all the asteroids above a certain hazardous size. It's something astronomers have been working on for generations; it's a very large, coordinated effort.

An asteroid impact is a preventable natural disaster. It's in part preventable because we have the technology, and it's in part preventable because it's predictable. For example, an earthquake — there's been lots of very hard work by very smart people, but you can't pinpoint exactly when they're going to happen, because the system of faults is extremely complicated. But asteroids are physically very simple. The paths they take through space are governed by gravity — and, to a lesser extent, sunlight — and so we can predict where these things are going for hundreds of years. Since we can find them and predict where they're going and move them, we have the ability now to prevent an asteroid impact on a large scale.

It's important to find them now, because any deflection strategy would need a lot of time to prepare. The best way to deflect them, to prepare for this event, is to look for all the asteroids right now.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space.com: Can you walk us through what would happen if a large asteroid of concern were identified?

Nugent: That's something that I interviewed Lindley Johnson about; Lindley Johnson is the planetary defense officer of NASA, which is the coolest title ever.

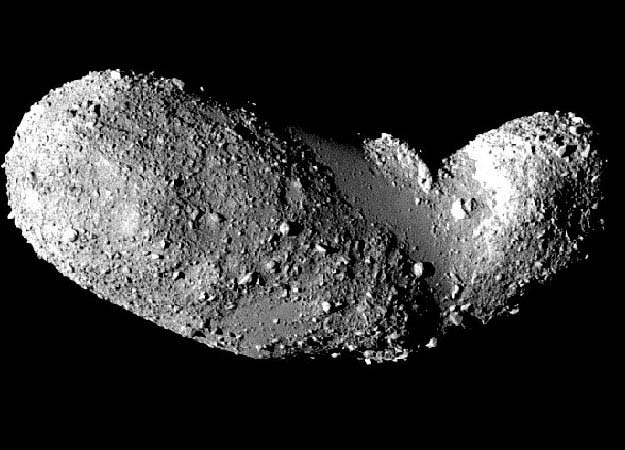

The asteroids are all very different. Some are made out of metal, and so they're very dense; some are made out of rock; and some are loosely held-together groups of rocks, called rubble piles. They have different physical properties; they can reflect a lot of light; they can be very dark; they can spin very quickly. Some make a full rotation in under a minute, and some have rotations that are over 100 hours. They're all very unique, and so what, exactly, you would want to do would depend on the individual asteroid. That's part of the reason why it's so important to find them now, because the response would have to be tailored to the individual event.

[Johnson] told me that the consensus of the scientist community was that there were three main ways being considered right now. The first would be a gravity tractor — so you put something in orbit of the asteroid, and you slowly tug it off its course. Another possibility is a kinetic impactor — so you hit it with something heavy, and it shoves it off its course a little bit; it changes the speed of the asteroid. And then, the last one is what everyone knows from Hollywood movies, which is nuclear detonation. Nuclear is the most flashy and the thing people think of first, but the problem with nuclear is, it's not very controllable.

Those other two methods you could be more precise about; there's more unknowns with the nuclear options than most people would like. To also be clear, it wouldn't be to send asteroid miners to drill and put a nuke in; you'd detonate it on the side and irradiate the surface. Again, the more time we have to figure out the best thing to do, I'm sure we could come up with a really good solution if we had enough time. [Three Ways To Deflect An Asteroid - Former Astronaut Explains (Video)]

Space.com: And certain asteroids would be better handled with specific strategies?

Nugent: If you had a rubble pile and you had enough time, a really nice solution for that may be a gravity tractor because that wouldn't have to touch the surface at all, and you could just tug it off its course [with] gravity. You would need enough time; it would depend on the size… These things have really interesting orbits when they get close to Earth. They're a little bit chaotic, and I mean that in the formal scientific sense of the word "chaotic," in that they're sensitive to initial conditions. The amount you have to move the asteroid isn't just like you have to move it one Earth distance; you could move it a smaller amount as well if you did it at the right time in advance, and you would be cleverly using Earth's gravity to get a positive result. You'd really have to study that individual case.

Space.com: So how many of the asteroids in Earth's neighborhood do we know about?

Nugent: You have to make some sort of size grouping here, because there's rocks of all different sizes out in space. There's things that are over a kilometer across, and there's things that are as small as a pea. You might intuitively grasp that the smaller the object, the more of them there are. Astronomers have divided these things into size classes, and one milestone that was reached relatively recently is that astronomers found over 90 percent of the asteroids 1 kilometer or larger that get close to Earth.

You also divide them into their orbits. We're not so concerned with finding all of the tiny main-belt asteroids between Mars and Jupiter; we want to find the ones near Earth. These are the ones with special orbits as well. … There's another goal that was set by the George E. Brown Jr. Near-Earth Object Act, which was to find over 90 percent of the asteroids 140 meters [460 feet] across and bigger. This is going down one size step to things that are still really big, but slightly smaller. That's the goal we're working towards now, and it's really exciting.

Space.com: It seems relatively common to see small asteroids just before they pass by, like the 3-meter [10 feet] one last week, which researchers saw 6 hours before flyby.

Nugent: Hopefully, we get more and more of these events. In the book, I talk about [the small asteroid] 2008 TC3, which was discovered by the Catalina Sky Survey. And that was awesome because we saw it in the sky, and they were able to track it, predict where it was going to come down over the Sudan and actually watch it come down. A flight diverted, took a slight detour and two Dutch pilots ended up seeing it come down. That's a very cool event. It's scientifically fascinating to be able to study something when it's in space and when it's in the ground.

Space.com: Can you talk about the different telescopes that are looking out for asteroids?

Nugent: There are five major surveys that make the bulk of the discoveries — though there's also small groups who find some, and that's really wonderful. [The main surveys] are LINEAR, in New Mexico; the Catalina Sky Survey; Spacewatch; Pan-STARRS; and NEOWISE. And they all have their different strengths; they work together very well to make a really good map of the sky. Most of these are using telescopes on the ground, and they're very classically what you would imagine: astronomers driving up to telescopes and working the telescopes on these remote mountains.

But the one I work on, NEOWISE, is a little different: It's a space-based infrared telescope. NEOWISE was originally launched as WISE, which was an astrophysics mission meant to observe the most luminous galaxies and coldest stars. But we repurposed it to find asteroids. NEOWISE has two goals: One is to characterize asteroids, figure out how big and how bright they are, really basic information about these bodies; and we also find asteroids. NEOWISE happens to be in infrared, which is really great because some asteroids are really reflective, and by very reflective, I mean that 40 percent of light is reflected, and some asteroids are about as dark as coal. These dark asteroids are hard to see when you're looking at the light reflected off of them because they're so dark, and they're in the blackness of space. But when we look at them in the infrared, they heat up. They emit light in the infrared, so they appear very bright in our images. We tend to find the large, dark asteroids.

Space.com: It's amazing that things like that are out there, still undiscovered.

Nugent: I think that, a lot of times, people have this idea that the solar system is entirely explored, that we have sent spacecraft to every planet, we've taken beautiful pictures of everything and that it's kind of done. You can open a textbook and [say], "Oh, we've mapped this." And it's really interesting to me that we haven't. There's so much left to discover. There are physical bodies, physical worlds that astronauts could visit, that we haven't found yet. Especially, there's these close approaches of asteroids. They pass within geosynchronous orbit sometimes, and they pass within the Earth and the moon. And that area seems very well explored; most people have this idea that we know exactly what's going on there. But because the Earth and the sun and the moon and all the asteroids are constantly moving relative to each other, we actually don't know everything in that region as it moves forward in time.

I think it's really exciting; there's a lot of unknowns, and I think a lot of people are excited to learn that there are new objects being discovered all the time. I happen to have in front of me the [International Astronomical Union's] Minor Planet Center website, and on the right side, they have these running tallies, and these are my favorite things. They break them up into near-Earth objects, and just general minor planets and comets. It says that today, March 6, [in this month], we've discovered 16 new near-Earth objects; this year, we've discovered 330. Last year was 1,893, and all time was 15,839. [As of March 13, those tallies were up to 38 this month, 352 this year, and 15,856 all time.] And the Minor Planet Center is keeping track of every single one, and you can watch that increment; this goes up every single day.

Interview edited for length. You can buy "Asteroid Hunters" at Amazon.com. Nugent also hosts a space podcast, Spacepod.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.