Astronaut's Rare Thunderstorm Photos from Space Reveal Stormy Science

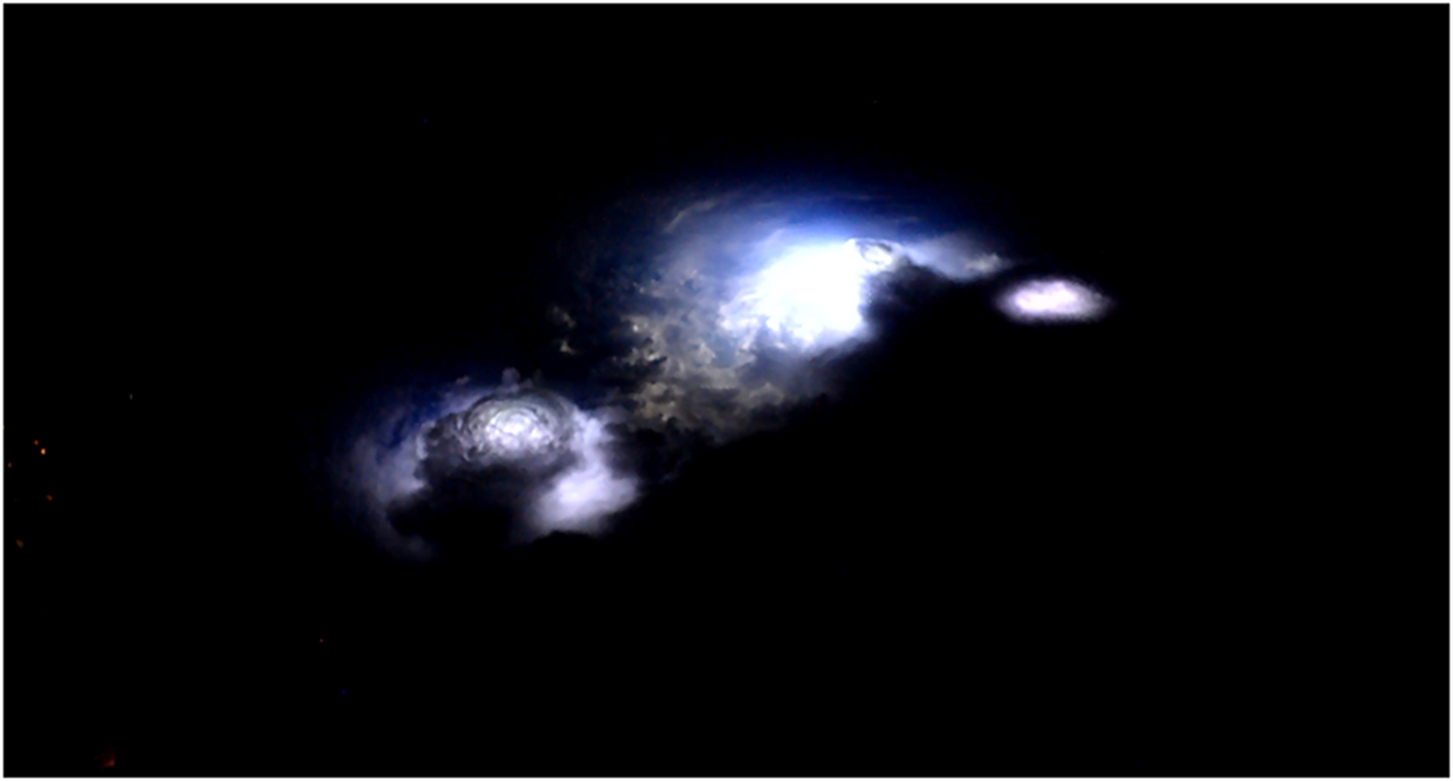

From the unique viewing location of the International Space Station (ISS), Danish astronaut Andreas Mogensen captured what may be the first ever photographs of strange and rarely-seen features of thunderstorms.

Scientists on the Thor experiment used the astronaut's snapshots to observe elusive electrical activity whose existence researchers had long debated. The astronaut's finds included a shot of a pulsating blue jet that stretched 25 miles (40 kilometers), a rare feature that scientists have a hard time studying, said a statement from the European Space Agency (ESA).

"The viewing condition and the resolution of the camera Andreas used surpasses conventional satellite observation," Olivier Chanrion, lead author of a paper about the experiment, told Space.com by email. Chanrion, a researcher at Denmark’s National Space Institute, led Thor, which required an astronaut on board the space station to photograph the hard-to-study upper layers of a thunderstorm. Results showed that powerful electrical discharges occurred at the top of the storms much more frequently than previously observed, the researchers said. [Astronaut Scott Kelly's Awesome Storm Photos from Space]

"The profuse activity Andreas Mogensen recorded from the ISS was new. We did not expect so much blue discharge sparking at the top of a cloud turret," Chanrion said.

Lightning striking again and again

Thunderstorms produce dazzling displays of lightning as seen from the ground, but the clouds shield other activity taking place in their uppermost layers. The electrical activity of these storms can affect the chemistry of the atmosphere, as anyone who has smelled ozone during a storm can attest; the strength of the effect depends on the strength, frequency, and types of electrical discharges.

As Mogensen flew over the Bay of Bengal aboard the station, traveling at 17,900 mph (28,800 km/h), he used the ISS's most sensitive camera to record the thunderstorm. His images were the first to capture pulsating discharges at the tops of storm clouds, the scientists said in a paper describing their research, which was published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

"They show the astonishing variety of forms that electrical activity can take as we continue to discover new varieties of discharges in and above thunderstorms," the researchers wrote.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The images also revealed blue, blob-like discharges in the surface layer of the clouds, stretching anywhere from 2.5 to 5.5 square miles (4 to 9 square kilometers) and occurring about 90 times per minute. This is the first observation of blue surface-discharges with these characteristics, the scientists reported in the paper.

The study also revealed red-colored tendrils created by "sprites" (powerful electric discharges), which last only a few milliseconds. sSprites form from irregularities in Earth's upper atmosphere. Their brief duration makes them difficult to detect, according to study co-author Torsten Neubert, also of Denmark's National Space Institute,.

"The perspective of the ISS means everything, together with a high-resolution, color camera," Neubert told Space.com.

The incredible photographs astounded the scientists, they said, revealing thunderstorm-atmosphere interactions that are not well-understood. The electrical strikes can affect the concentrations of greenhouse gases, playing a significant role in moving gases between the layers of the atmosphere, Neubert said.

"We found the top of the thundercloud much more electrically active than anticipated," Neubert said. "That was a surprise. It means that thunderstorms affect the lower stratosphere more than we thought."

View from above

At any given moment, nearly 1,800 thunderstorms occur somewhere in the world, according to the National Weather Service. While making ground observations of these storms is fairly simple, studying the upper layers can be more challenging. The cloud itself can block activity at the top, absorbing the blue light created by the lightning, Chanrion said.

Thunderstorms "have been observed from aircraft, but usually the aircraft circles around a storm at some distance for safety reasons," Neubert said. "Furthermore, very few aircraft can get to the high altitudes required to look down on storm clouds."

The handful of aircraft that can travel to such high altitudes, whether they are piloted or drones, usually fly in the daylight, when it is harder to spot activity, Neubert said.

Balloons are another option, but they must be launched when the wind is quiet, Neubert said. That usually happens in the early morning, but thunderstorms are more apt to develop over the afternoon, he said.

"One has to be lucky to get the balloon to fly where it is interesting," he said.

Satellites can reach the necessary height, but often lack the necessary resolution to glimpse the details of the cloud structure, he said.

With these challenges in mind, Neubert proposed requesting that the first Danish astronaut on board the space station photograph thunderstorms for the Danish-led experiment. In September 2015, Mogensen captured brief videos of thunderstorms over India that he took in the cupola of the space station, sending them to ground within hours.

But the astronaut didn't rush to the window with his camera when he saw thunderstorms on Earth. The team on the ground had to accurately predict thunderstorms, then coordinate them with Mogensen's schedule at least three days in advance.

"Remember that thunderstorms come and go, and the Thor experiment time has to be when the ISS flies over a thunderstorm," Neubert said. "Most other experiments [the astronauts] do, do not have this complexity."

Thor's incredible images may provide a taste of things to come. The researchers said they still have questions about how common the activity observed in the single storm might be. The experiment was a precursor for ESA's Atmosphere-Space Interactions Monitor (ASIM) experiment, for which Neubert is the lead scientist. He said he expects that ASIM should be installed on the station at either the end of 2017 or the beginning of 2018.

"We hope to convince other astronauts to continue Thor when ASIM is installed on the ISS so we can get supplementary observations," Neubert said.

"It is not every day that you get to capture a new weather phenomena on film, so I am very pleased with the result — but even more so that researchers will be able to investigate these intriguing thunderstorms in more detail soon," Mogensen said in the statement.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd Facebook or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky