Titan's Trick Explained: 'Magic Islands' on Saturn Moon May Be Bubbles

Mysterious bright anomalies known as "magic islands" that wink in and out of existence on the seas of Saturn's largest moon, Titan, may be streams of bubbles, a new model suggests.

Such bubbles, each up to more than an inch (2.5 centimeters) wide, might complicate any future missions seeking to explore Titan's seas, to the study's researchers said.

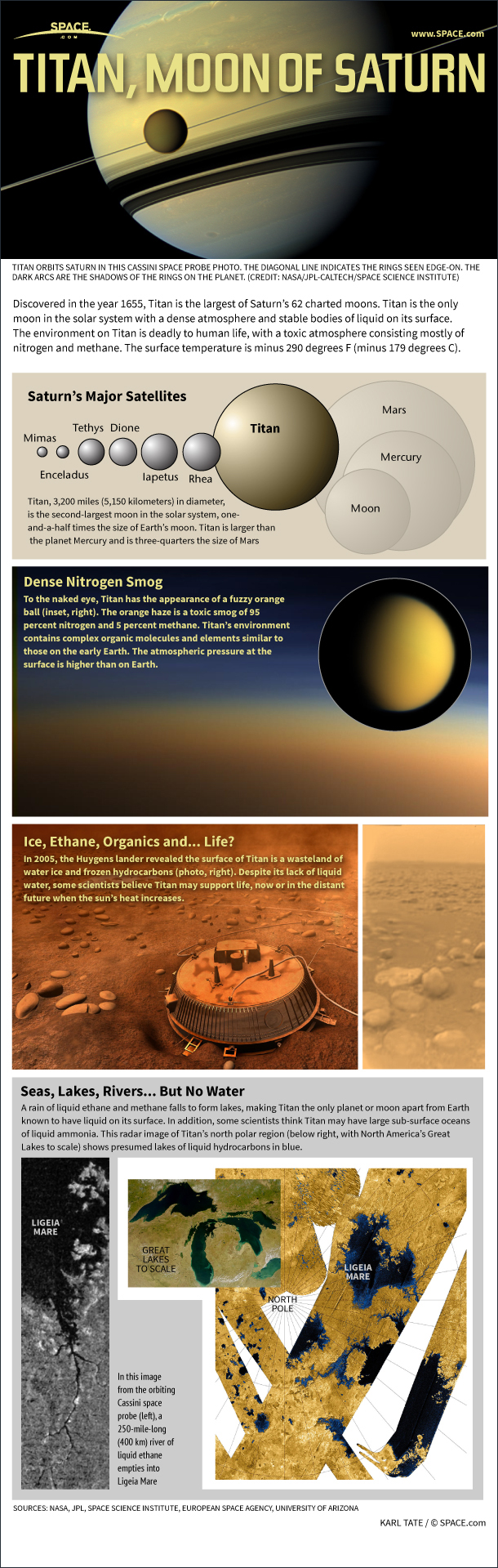

Titan is bigger than the planet Mercury, making the natural satellite the largest of the more than 60 known moons orbiting Saturn. It is also the only extraterrestrial body known to regularly support liquid on its surface, with seas and lakes likely made of nitrogen, methane and ethane, researchers have said. [Titan in Pictures: Amaznig Photos of Saturn's Big Moon]

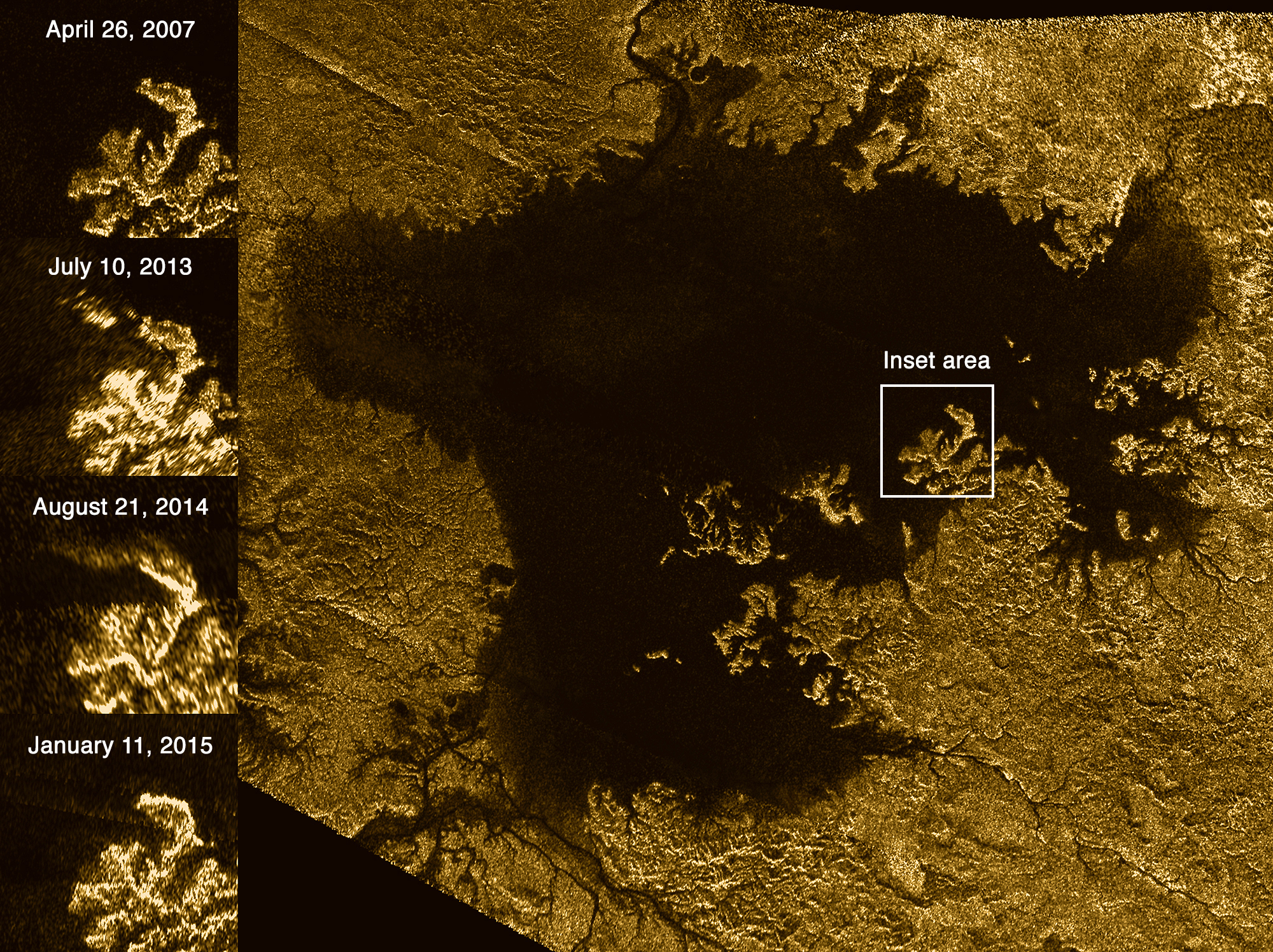

In 2013, using radar aboard NASA's Cassini spacecraft, researchers peered through Titan's thick, hazy atmosphere to analyze the second-largest sea on the moon, Ligeia Mare. Titan's seas and lakes usually appear dark, but Cassini detected bright anomalies in Ligeia Mare that mysteriously disappeared after subsequent observations.

"The physical process behind this strange behavior was, up to now, absolutely not understood," study lead author Daniel Cordier, a planetary scientist at the University of Reims Champagne-Ardenne in France, told Space.com.

Previous research suggested these playfully named magic islands were not alien creatures or spacecraft, but potentially gas bubbles or floating solids. Now, Cordier and his colleagues suggest that these anomalies are due to fizzing in Titan's unstable seas.

To learn more about the magic islands, the researchers developed computer models of how gases and liquids might behave in the frigid seas of Titan. The scientists based their models in part on experimental data previously collected by the oil and gas industry about how similar fluids act under pressure when deep underground.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new findings suggest that on Titan, surface fluids are usually mixtures richer in methane, while deeper fluids are mixtures rich in ethane. Since the surface fluids are in contact with Titan's nitrogen-rich atmosphere, they are rich in nitrogen as well, the study said.

The researchers suggested that wind, tides, or the effects of heating and cooling may force surface mixtures to flow downward. The liquids in these sinking mixtures then separate because of the increased pressure found at lower depths. Nitrogen gas bubbles released by these separating liquids then rise back to the surface. Bubbles are highly reflective to radio waves, and so look bright under radar scans, the researchers said.

The calculations suggest that the bubbles can reach up to 1.8 inches (4.6 cm) in width and likely form at depths of about 330 to 660 feet (100 to 200 meters). This bubbling is only temporary, which explains why the Cassini spacecraft did not always see it, the researchers said.

Cordier noted that if future missions seek to deploy submarines to Titan's seas, "possible instabilities of the liquid at the sea bottom have to be taken into account."

The scientists detailed their findings online Monday (April 18) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us