Brrr! How Much Can Temperatures Drop During a Total Solar Eclipse?

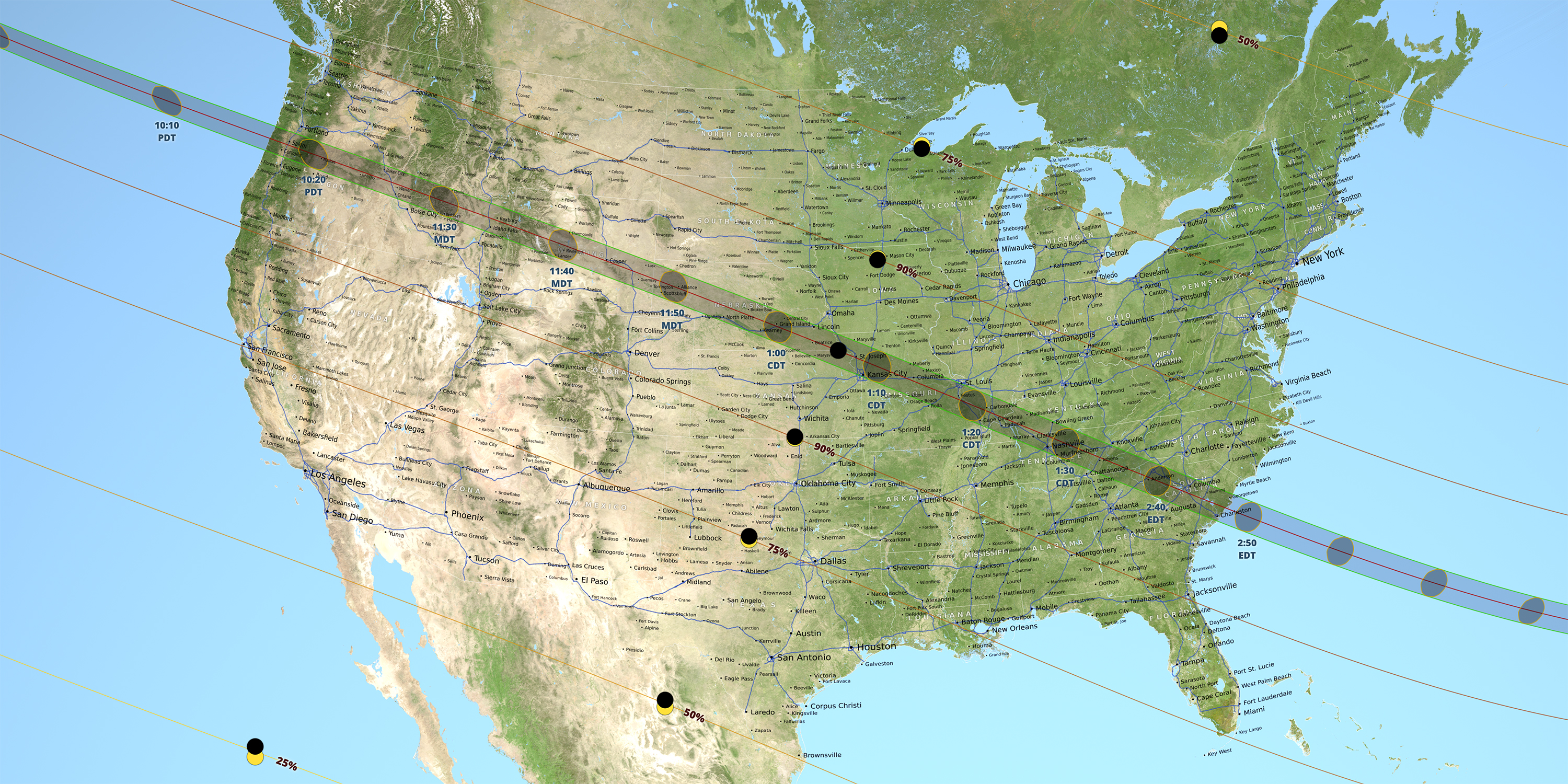

During the total solar eclipse on Aug. 21, 2017, the moon will completely cover the disk of the sun from Oregon to South Carolina. During this period of "totality," eclipse observers will likely report feeling a sudden drop in temperature. Just how much does the mercury drop during this celestial event?

During the total solar eclipse on Dec. 9, 1834, the Gettysburg Republican Banner reported that in some places, the eclipse caused the temperature to drop by as much as 28 degrees Fahrenheit, from 78 degrees F to 50 degrees F (25 degrees Celsius to 10 degrees C). During a total solar eclipse on the Norwegian island of Svalbard in March 2015, temperatures dropped from 8 degrees F to minus 7 degrees F (minus 13 C to minus 21 degrees C).

The change in temperature during a total eclipse will vary based on location and time of year. The temperature change created by the loss of light from the sun's disk will be similar to the difference between the temperature at midday and the temperature just after sunset, except the change will occur more suddenly, which is why this is often one of the very noticeable effects of a total solar eclipse.

Rick Feinberg, head of media relations for the American Astronomical Society, says people can expect an average drop of about 10 degrees F (about 5 degrees C).

There are written accounts of total solar eclipses going back millennia. And yet, there seems to be lacking any long-term, consistent effort to measure many of the local effects of total solar eclipses — such as the drop in temperature — according to Jay Pasachoff, an astronomer at Williams College who studies eclipses.

Pasachoff and his colleague Marcos Peñaloza-Murillo are working to conduct standardized measurements of many of the local effects of total solar eclipses. The pair produced their first publication on this topic in the Aug. 22, 2016, issue of the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, where they reported on the change in temperature in Svalbard in 2015. The entire issue of that journal was dedicated to "eclipse weather," or the study of the various atmospheric effects that take place during total solar eclipses. The two researchers will make more measurements during the total solar eclipse on Aug. 21, 2017, from Salem, Oregon.

Pasachoff and Peñaloza-Murillo measured the temperature at a height of about 5 feet (1.5 meters) above the ground, and found that the lowest daytime temperature occurred 2 minutes after the end of totality. That might be because most of the sun's energy doesn't heat the air directly. The Earth's atmosphere is a good insulator, meaning it doesn't exchange heat easily. Most of the sun's energy warms the ground, which then gradually warms the air; the warm air rises, and cool air settles on the ground, creating a convection cycle of heating. This delayed transfer of heat could explain the slight delay in the cooling of the air during totality.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Total solar eclipses happen, on average, about every 18 months, but they are visible only on a narrow strip of land. (The Aug. 21 total solar eclipse will be visible along a 70-mile-wide path that crosses the continental U.S.) So-called "eclipse hunters" often have to travel to remote parts of the globe to see these cosmic events. That means it could take Pasachoff and Peñaloza-Murillo many years to gather data on "eclipse weather" from a significant number of total eclipses.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter