The potentially Earth-like planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system may not be so conducive to life after all, two new studies report.

Intense radiation and particles streaming from their host star have likely taken a huge toll on all seven of these worlds, even the three that apparently lie within the "habitable zone," where liquid water could theoretically exist on a planet's surface, according to the new research.

"Because of the onslaught by the star's radiation, our results suggest the atmosphere on planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system would largely be destroyed," Avi Loeb, co-author of one of the studies, said in a statement. [Meet the 7 Earth-Size Planets of TRAPPIST-1]

"This would hurt the chances of life forming or persisting," added Loeb, who chairs Harvard's astronomy department and who also works at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

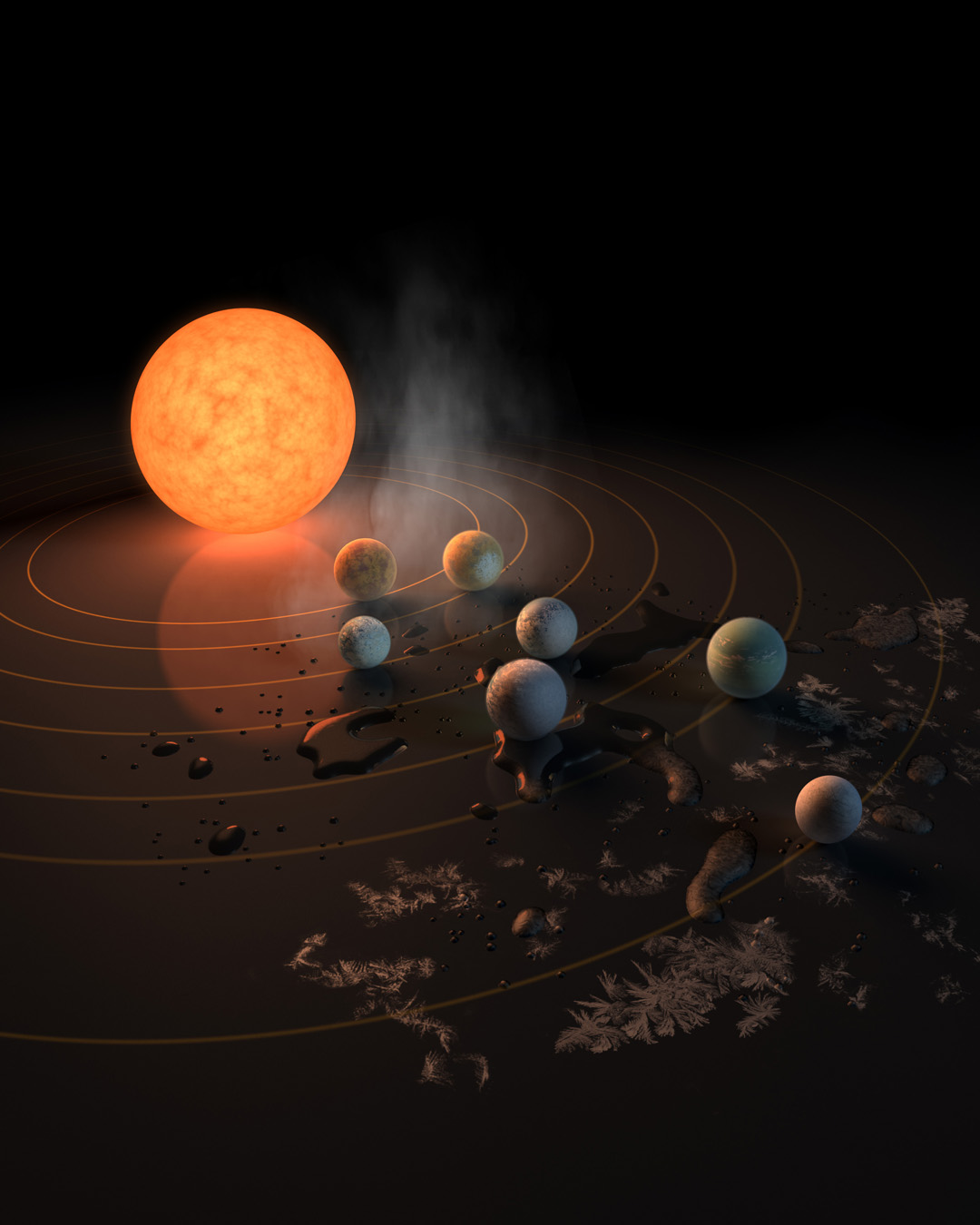

In May 2016, astronomers announced the discovery of three roughly Earth-size planets circling the red dwarf star TRAPPIST-1, which is just 8 percent as massive as the sun and lies about 39 light-years from Earth. Further observation revealed that the star hosts seven rocky planets, three of which seem to orbit in the habitable zone (HZ).

But just being in the habitable zone doesn't necessarily make a planet habitable; there are many more factors involved, stressed Loeb and the study's lead author, Manasvi Lingam of Harvard.

One of these factors is stellar radiation. TRAPPIST-1 is quite dim, so its habitable zone is very close-in; even the most far-flung TRAPPIST-1 world orbits a mere 5.6 million miles (9 million kilometers) or so from the star. (For comparison, the innermost planet in Earth's solar system, Mercury, lies 36 million miles, or 58 million km, from the sun on average.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Because of this proximity, the TRAPPIST-1 planets are likely barraged by radiation, Lingam and Loeb said. Their modeling work suggests that these worlds receive far higher ultraviolet (UV) fluxes than Earth does — so much, in fact, that the exoplanets' atmospheres may have been stripped away.

The same reasoning holds for Proxima b, a potentially Earth-like world that orbits a red dwarf just 4.3 light-years from Earth.

"Earth-sized planets in the HZ around M-dwarfs [another name for red dwarfs] are presumably much less likely to be habitable, conceivably by several orders of magnitude, when compared with the Earth-sun system," Lingam and Loeb wrote in their study, which was published this month in the International Journal of Astrobiology.

The second study, led by researchers from the CfA and the University of Massachusetts in Lowell, reached similar conclusions. Modeling work by this team suggested that the stellar wind — the stream of particles flowing constantly from a star — exerts pressures on the TRAPPIST-1 worlds that are 1,000 to 100,000 times greater than the solar wind exerts on Earth.

But it gets worse. Because the TRAPPIST-1 system is so tightly packed, the star's magnetic field has likely connected with those of the planets, allowing stellar-wind particles to flow directly onto the worlds' atmospheres, the researchers found. This has probably caused atmospheric degradation, and the worlds may even have lost their air entirely.

"The Earth's magnetic field acts like a shield against the potentially damaging effects of the solar wind," study leader Cecilia Garraffo of the CfA said in the same statement. "If Earth were much closer to the sun and subjected to the onslaught of particles like the TRAPPIST-1 star delivers, our planetary shield would fail pretty quickly."

The Garraffo-led study has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters; you can read it at the online preprint site arXiv.org.

While these results aren't great news for people hoping that life exists in the TRAPPIST-1 system, they don't rule out the possibility, researchers insisted.

"We're definitely not saying people should give up searching for life around red dwarf stars," Garraffo's co-author Jeremy Drake, also from the CfA, said in the same statement. "But our work and the work of our colleagues shows we should also target as many stars as possible that are more like the sun."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.