Voyager 1, Humanity's Farthest Spacecraft, Marks 40 Years in Space

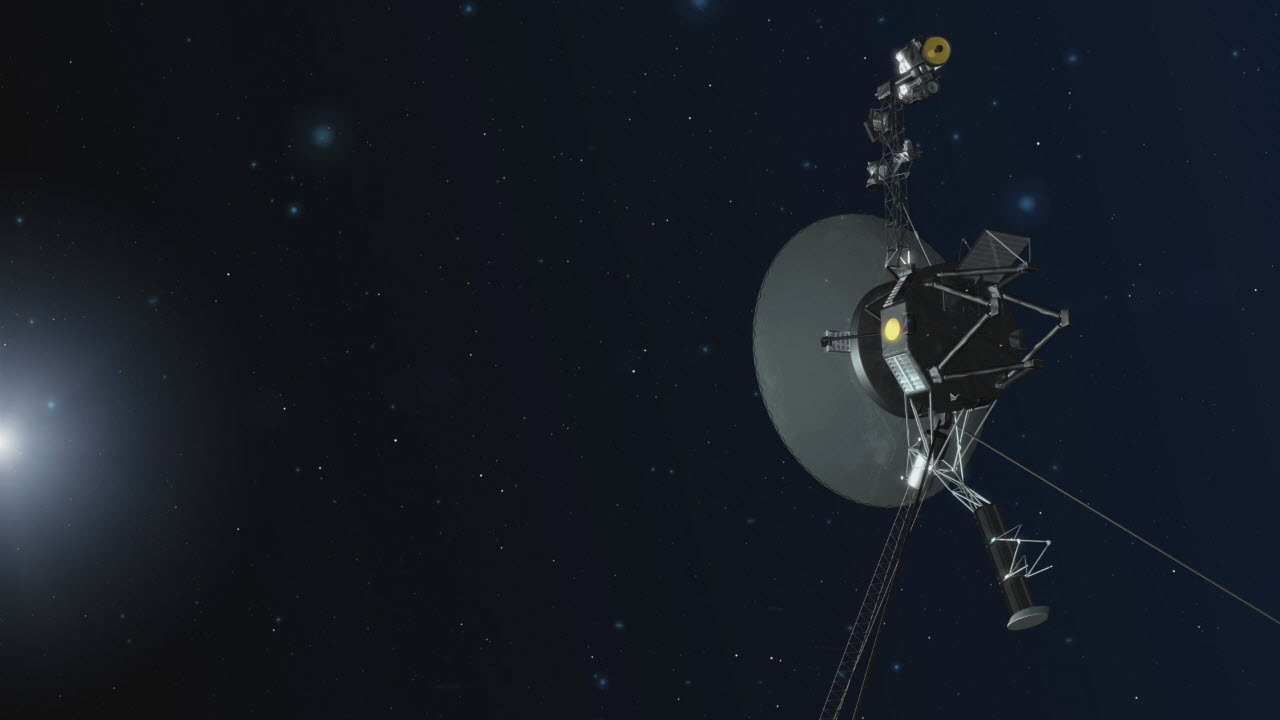

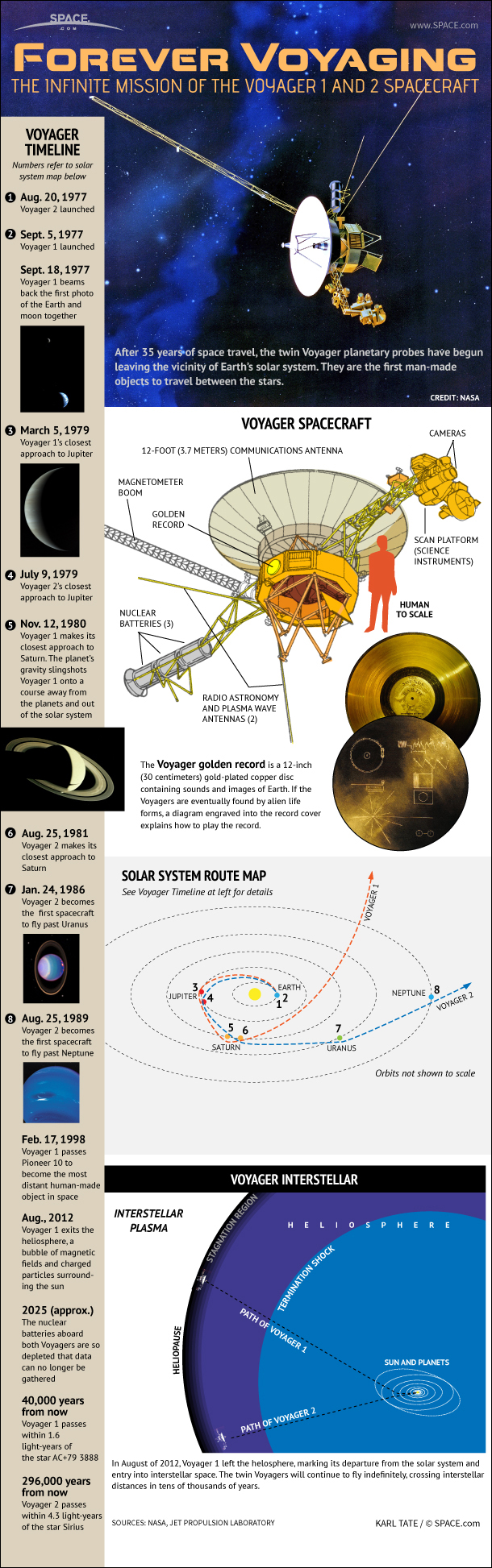

NASA's Voyager 1 probe lifted off on Sept. 5, 1977, a few weeks after its twin, Voyager 2. Together, the two Voyager spacecraft performed an epic "Grand Tour" of the solar system's giant planets, flying by Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

But their work didn't stop there. Both spacecraft kept flying, pushing farther and farther into the dark, cold and little-known realms far from the sun. [Voyager: 40 Epic Photos from NASA's Grand Tour]

Then, on Aug. 25, 2012, Voyager 1 popped free into interstellar space, becoming the first human-made object ever to do so. Voyager 2, which took a different route through the solar system, will likely exit the sun's sphere of influence in the next few years as well, mission team members have said.

And both spacecraft still have their eyes and ears open, all these decades later.

"It's amazing that the two spacecraft are still working after 40 years," said Ed Stone, who has been a Voyager project scientist since the mission's inception in 1972. [Voyager at 40: An Interview with Ed Stone]

"When we launched, the Space Age itself was only 20 years old, so this is an unparalleled journey, and we're still in the process of seeing what's out there," Stone, who's based at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, told Space.com.

As of Friday (Sept. 1), Voyager 1 was a whopping 12.97 billion miles (20.87 billion kilometers) from Earth — more than 139 times the distance from our planet to the sun. Voyager 2 was about 10.67 billion miles (17.17 billion km) from its home planet.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Grand Tour

Voyager 1 cruised by Jupiter in March 1979 and Saturn in November 1980. This latter encounter also included a close flyby of Saturn's huge moon Titan. [Voyager at 40: NASA Retrospective Videos Look Back]

Voyager 2 pulled off its own Jupiter-Saturn double, flying by those two planets in July 1979 and August 1981, respectively. Then, the spacecraft had encounters with Uranus, in January 1986, and Neptune, in August 1989.

During this Grand Tour, both spacecraft beamed home data that surprised and excited scientists.

For example, before the Voyagers launched, the only known active volcanoes were here on Earth. But Voyager 1 spotted eight erupting volcanoes on the Jupiter moon Io, showing that the little world is far more volcanically active than our own planet. [More Photos from the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 Probes]

The mission also determined that Titan has a nitrogen-dominated atmosphere, just as Earth does.

"It may, in some important ways, resemble what the Earth's atmosphere was like before life evolved and created the oxygen that we all breathe," Stone said.

Furthermore, Voyager observations suggested that the Jupiter moon Europa may harbor an ocean of water beneath its icy crust — a notion that subsequent NASA missions have pretty much confirmed.

"I think what Voyager has done is reveal how diverse the planets and the moons and the rings, and the magnetic fields of the planets, are," Stone said. "Our terracentric view was just much narrower than, in fact, reality."

Interstellar ambassadors

Voyager 1 has found that cosmic radiation is incredibly intense beyond the sun's protective bubble, Stone said. The probe is also revealing how the "wind" of charged particles from the sun interact with the winds of other stars. [5 Surprising Facts About NASA's Voyager Probes]

Meanwhile, Voyager 2 is studying the environment near the solar system's edge. After it enters interstellar space, Voyager 2 will make its own measurements, revealing more about this mysterious region.

But this work cannot go on forever.

The Voyagers are powered by radioisotope thermoelectric generators, which convert the heat produced by the radioactive decay of plutonium-238 into electricity. And that heat is waning.

"We have about 10 years or so of power remaining until we have only enough to power the spacecraft itself, without any of the instruments," Stone said.

But even after the probes power down, they'll continue speeding through the cosmos for eons, making one lap around the Milky Way every 225 million years.

What if intelligent aliens intercept the Voyagers during this journey? Well, the probes' makers planned for this unlikely scenario: Both Voyagers carry a copy of the "Golden Record," which is full of images and sounds of Earth, as well as directions to our planet.

In the far future, the Voyagers will "be our silent ambassadors, with messages about where the place was that sent them so many billions of years earlier," Stone said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.