Mars May Have a Porous Crust, Gravity Map Suggests

NASA scientists are one step closer to understanding the evolution of Mars.

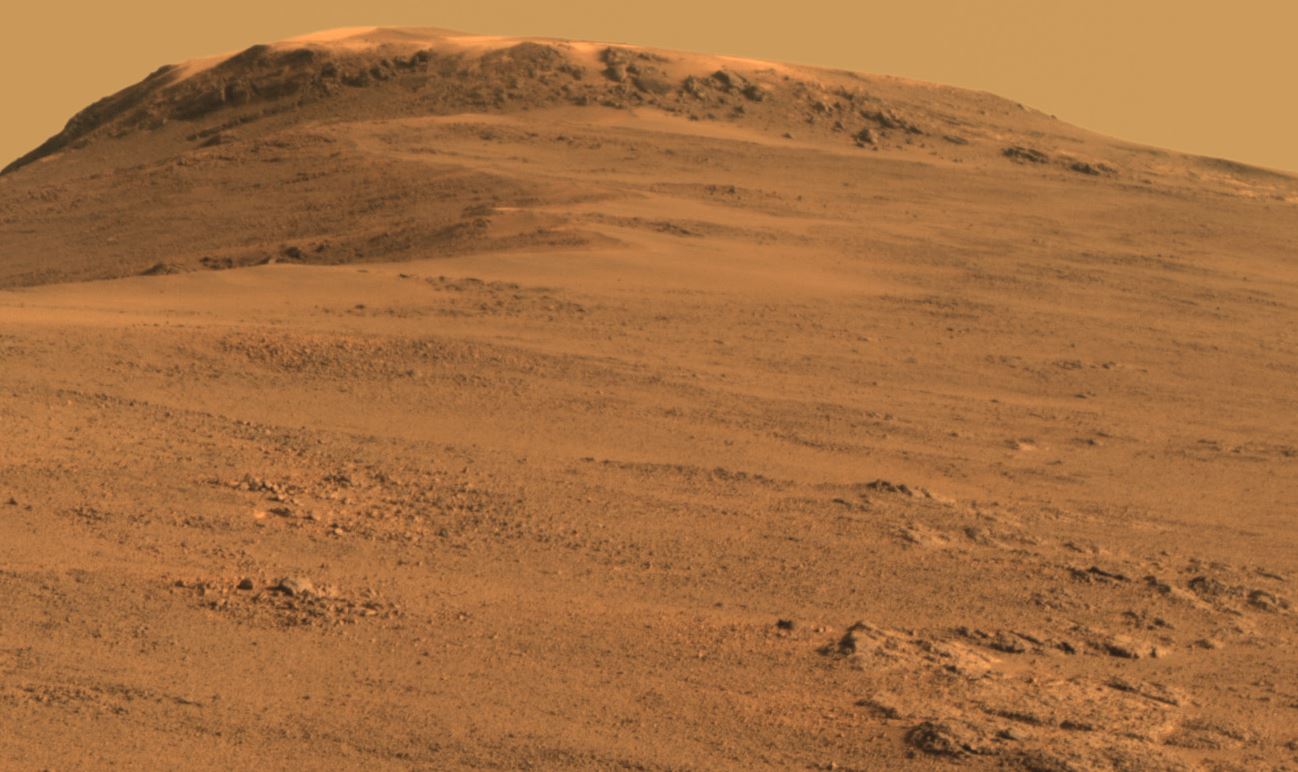

New evidence shows that the Red Planet's outer crust, which is about 30 miles (50 kilometers) thick, is porous and not as dense as previously thought.

"A lower density could have important implications about Mars' formation," Sander Goossens, a researcher at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Maryland and lead author of the new study, said in a statement from NASA. [Curiosity Rover Climbing Steep Martian Ridge (Photos)]

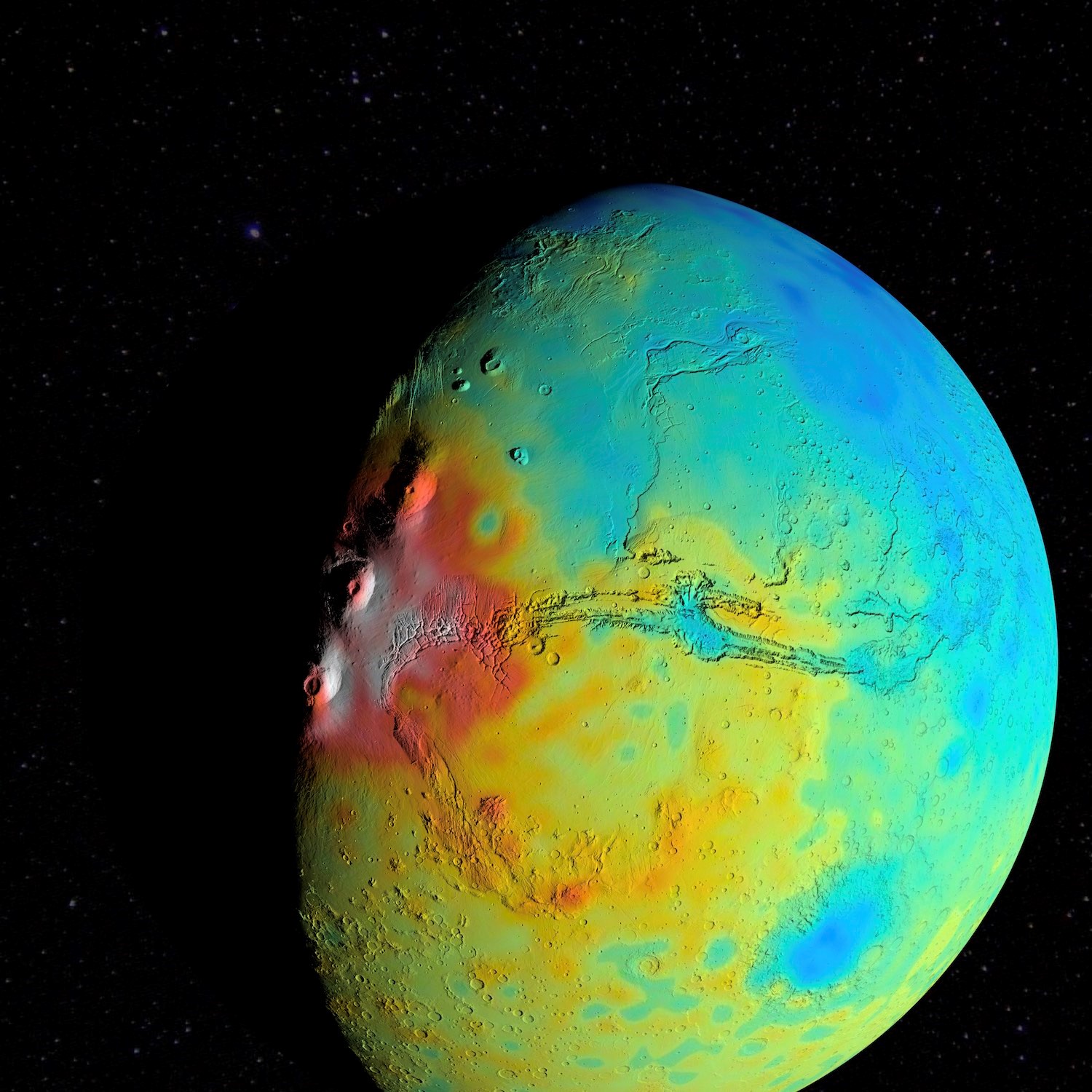

GSFC's Planetary Geodynamics Laboratory made its crust discoveries by looking at Mars' gravity field, which was previously derived using satellite tracking data and advanced mathematical tools. Goossens and his team used the gravity field in a modified technique, which correlates the field with precise measurements of Mars' topography, or surface features, to make findings of Mars' crust density more accurate.

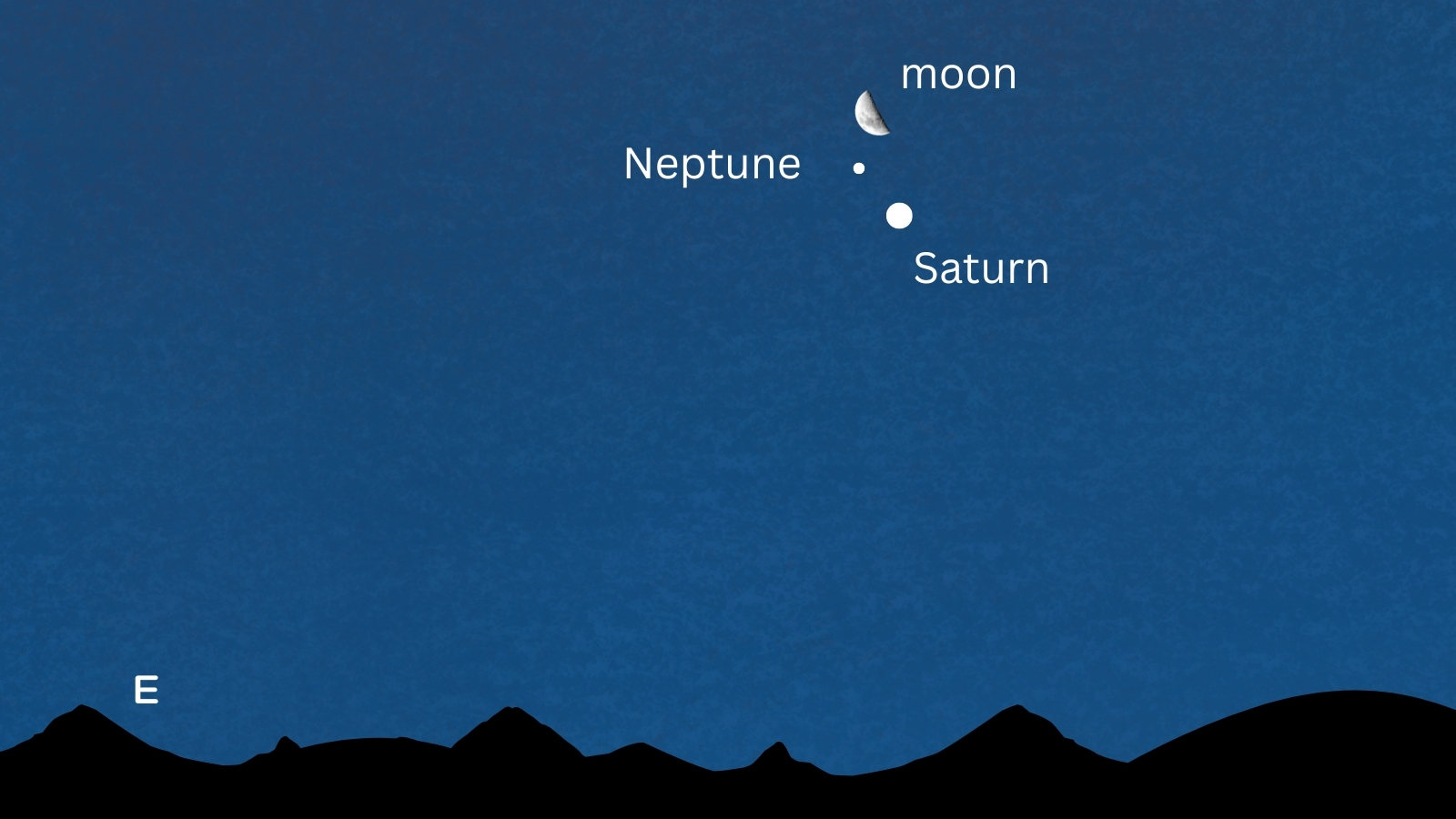

Gravity fields allow scientists to understand Mars on a deeper level, literally. Similar techniques have been used, for example,to investigate the moon's subterranean composition and history. Researchers measure a planetary body's gravity field by tracking tiny changes in satellites' orbits as they pass over specific areas that have differing gravitational pulls.

According to NASA, the Martian crust was found to have an average density of 2,582 kilograms per meter cubed (about 161 lbs. per cubic foot), or about the same average density as the crust on Earth's moon.

Previous estimates of Martian crust density relied more heavily on looking at the composition of the soil and the rocks themselves. That's because up until now, the data sets that would produce gravity maps had a low resolution, NASA said. By comparison, the gravity field for Earth is very detailed, because the data sets have a high resolution, according to NASA.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"As this story comes together, we're coming to the conclusion that it's not enough just to know the composition of the rocks," Goddard planetary geologist Greg Neumann, co-author on the paper, said in the statement. "We also need to know how the rocks have been reworked over time."

To get findings that were more precise, Goossens and his team developed a technique to make correlations between Mars' topography— in particular, changes in elevation — and the planet's gravity field. Once they tested their new technique on Earth's moon, and found that the method successfully produced results that matched those found by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL), the team used its model to analyze Martian surface density.

"With this approach, we were able to squeeze out more information about the gravity field from the existing data sets," Goddard geophysicist Terence Sabaka, also a study co-author, said in the statement.

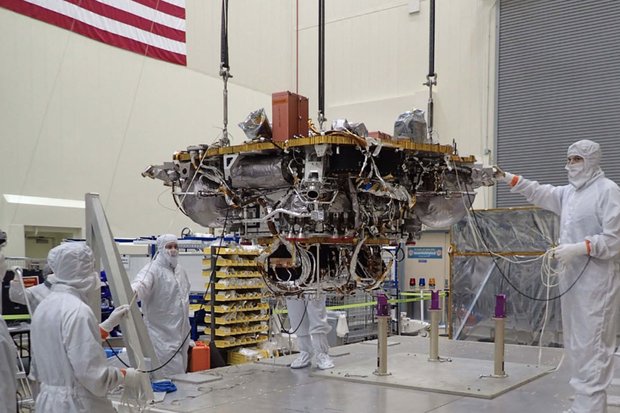

NASA's Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport (InSight) mission is expected to provide measurements that can verify Goossens' findings, in much the same way that GRAIL verified the lunar-density testing, according to the statement. InSight is scheduled to launch in 2018 with the Discovery Program mission, and when it arrives on Mars, InSight can probe the interior of this rust-colored neighbor planet.

The new work was detailed Aug. 5 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.