Sputnik's Beeping Legacy: Satellite's Simplicity Made It Iconic 60 Years Ago

In October 1957, amateur radio operators monitored the first signal from a spacefaring civilization — and it was us.

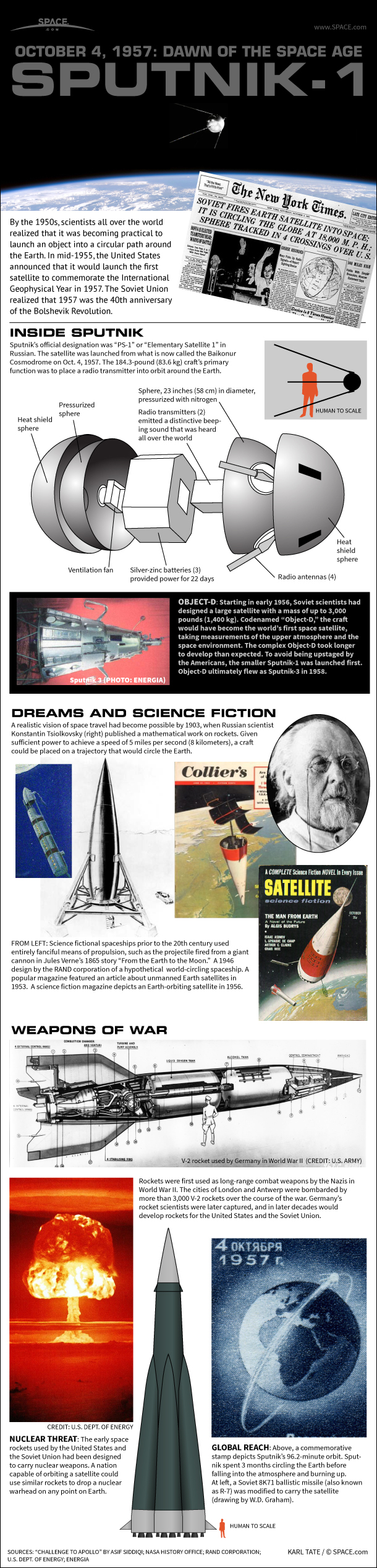

Sputnik 1, the first satellite to orbit the Earth, launched on Oct. 4 of that year from a site in Kazakhstan, then a part of the USSR. That site is now the Baikonur Cosmodrome; at the time it was site 1/5 at the Tyuratam range.

The Soviets had planned on a sophisticated scientific satellite, according to Cathy Lewis, curator of international space programs at the National Air and Space Museum at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. But they felt they were under time pressure; they wanted a launch as soon as possible because even then they had a sense of urgency. "They needed something very simple," she told Space.com. [Sputnik 1! 7 Fun Facts About Humanity's First Satellite]

What they launched had only a set of batteries, a transmitter and a pressure-activated switch that could tell ground controllers if the 23-inch (58 centimeter) diameter sphere was punctured by a micrometeoroid, Lewis said.

The USSR had been planning satellite launches since January 1956, and the United States since 1955. Both countries planned for their first launches to take place during what had been dubbed the International Geophysical Year, which ran from July 1, 1957, to Dec. 31, 1958. Coincidentally, the IGY was intended to mark a new period of cooperation between the United States, the USSR and other nations. Neither planned launch announcement got much attention until the USSR launched Sputnik and surprised the world.

"There was panic," Lewis said. "For the first time that harsh reality of the fear of nuclear weapons landing came to life. You were not going to have a warning of fleets of bombers."

In the United States, the shock was in part driven by a belief in American technological superiority.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The U.S. had an image of the Soviets as being technologically limited," said Matt Bille, a historian and author of "The First Space Race" (Texas A&M University Press, 2004). "If not outright backward. While the military had some of this sentiment, the August launch of an R7 (intercontinental ballistic missile) had generally awakened them." [Sputnik 1 in Photos: The World's First Satellite]

Bille added that then-President Dwight Eisenhower was not a technically oriented person and was often baffled by the public's reaction to Sputnik. The U.S. already had a missile program and a fledgling space program, and Eisenhower saw them as going well. In fact, the U.S. launched the first intercontinental ballistic missile months before the USSR did.

The Sputnik launch also drove Eisenhower to push for funding for science education at many levels, from grade school to college, via the National Defense Education Act, signed into law in 1958. Lewis said the country's experience in World War II had played a part in this — it was clear during the war that there weren't enough people with technical skills. Bille added that major publications, including U.S. News and World Report, had been lamenting the state of science education in the country, and Sputnik gave an additional push to improve.

The Sputnik launches were more than just a wake-up call for the U.S. In the scramble to show that the United States could stay ahead technologically, the space race was born, and with John F. Kennedy's announcement that the United States was going to attempt to send a man (it was going to be a man, no question) to the moon and bring him back, the die was cast. And there were other political effects; Kennedy, in the late 1950s, ran part of his campaign on the idea that Eisenhower, ever a fiscal conservative, was weak on defense and that the Russians had a sizable advantage in that area. Sputnik, Lewis said, was a gift to people pushing that idea. [Giant Leaps: Milestones of Human Spaceflight]

Bille said one reason the missile-gap concept had currency was that before satellite surveillance, few knew much about what was happening in the USSR at all.

In that sense, Sputnik enabled satellite surveillance, Lewis said. Before the satellite's launch there was some debate over "open skies" — whether spacecraft could fly over the territory of other nations. Aircraft were barred from doing so. Sputnik, Lewis said, made the question moot, because Sputnik flew over the U.S. in the course of its orbit, and therefore U.S. satellites could fly over the Soviet Union.

Even though the Soviets were unable to launch the more ambitious science payload, Lewis said that was part of Sputnik's enduring appeal. The satellite's beeps could be picked up by amateur radio operators; anyone could listen. That wouldn't have been the case for a true science instrument. Today, Sputnik's shape is in the logo of the Russian rocket company Energia, and it gave its name to the "Sputnik chandelier" design that became popular in the 1960s.

And beyond its physical appeal, "there's a simplicity and beauty in being first," Lewis said.

You can follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.