To Nuke an Asteroid, How Powerful a Bomb Do You Need?

Humanity now has a better idea of just how powerful a nuke you'd need to take out an incoming asteroid.

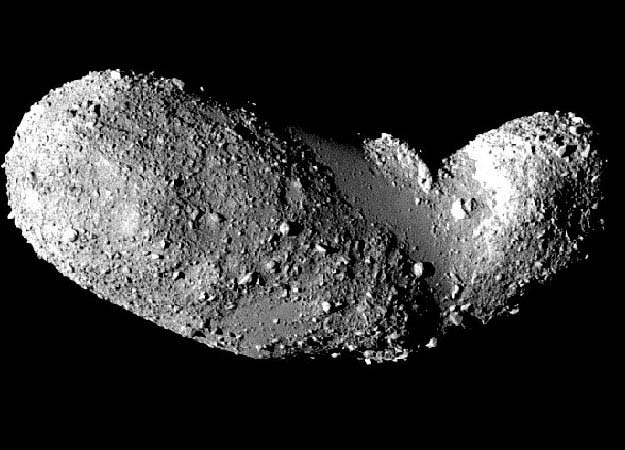

Researchers in Russia have modeled the destruction of dangerous space rocks in the lab, using tiny asteroid replicas and laser blasts to mimic the effect of nuclear warheads.

The team determined, among other things, that it would probably take a 3-megaton nuclear bomb to obliterate a 650-foot-wide (200 meters) stony asteroid. And any nuke's destructive power would be increased by exploding it inside a crater or cavity within the space rock, the researchers found. [Potentially Dangerous Asteroids (Images)]

For perspective, the atomic bombs that the United States dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II had explosive yields of about 15 kilotons and 20 kilotons, respectively. One megaton is equivalent to 1,000 kilotons. The most powerful nuclear weapon ever built, the Soviet Union's "Tsar Bomba" hydrogen bomb, had a yield of about 50 megatons. (The USSR detonated the Tsar Bomba device on Oct. 30, 1961, over the Novaya Zemlya island chain in the Arctic.)

For the new study, the researchers manufactured tiny artificial asteroids, basing their structure and composition on a piece of the space rock that exploded over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk in February 2013. The meteorite the team used was recovered from the bottom of Russia's Lake Chebarkul, the researchers said.

The study team then placed their fake asteroids, which had a variety of shapes, in a vacuum chamber and zapped them with brief laser pulses. The scientists found that a 500-joule-per-gram laser blast was required to break apart a model space rock 0.3 inches to 0.4 inches in diameter (8 to 10 millimeters), if that blast were directed at a premade cavity in the "asteroid." Without the cavity, the necessary energy was about 650 joules per gram.

The researchers scaled up these results to arrive at their conclusions regarding the 650-foot incoming asteroid. Their experiments also suggested that no advantage is gained by rationing out the energy input over multiple pulses. So, one powerful nuclear explosion would likely be just as effective as a series of smaller ones that added up to the same cumulative energetic yield, team members said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new study — which was published in the Russian edition of the Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics, and will soon appear in the journal's English version — modeled just stony asteroids. In future work, the researchers plan to extend their experiments to metallic space rocks, and to investigate in more depth how an asteroid's shape and its cavities may affect nuking attempts.

"By accumulating coefficients and dependencies for asteroids of different types, we enable rapid modeling of the explosion so that the destruction criteria can be calculated promptly. At the moment, there are no asteroid threats, so our team has the time to perfect this technique for use later in preventing a planetary disaster," study co-author Vladimir Yufa, an associate professor in the department of Applied Physics and the department of Laser Systems and Structured Materials at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, said in a statement.

"We're also looking into the possibility of deflecting an asteroid without destroying it and hope for international engagement," Yufa added.

Speaking of deflection — that's the strategy humanity would employ whenever possible to deal with a potentially dangerous asteroid. There are various ways to do this, like slamming (non-nuclear) "kinetic impactors" into the space rock and launching probes to fly alongside it for months or years, gradually nudging it off course via gravitational interactions.

But deflection may not be feasible in some scenarios, astronomers stress. If a very large asteroid is discovered just weeks away from a potential impact, for example, then blowing it apart with a nuke would probably be humanity's only option.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.