NASA's Next Mars Lander Will Look Deep to Understand the Red Planet — and Earth

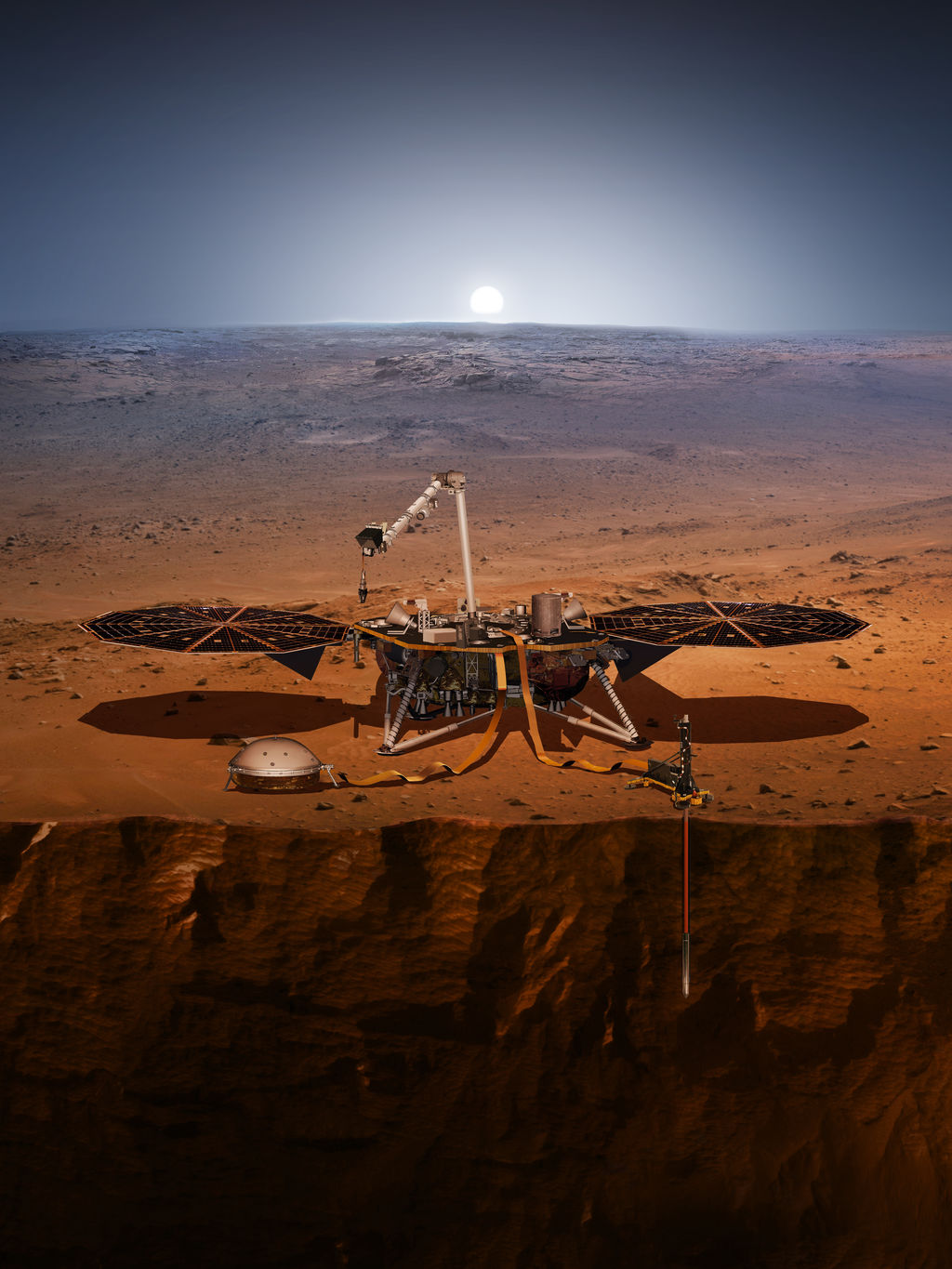

NASA's next Mars lander, InSight, is set to launch May 5 at the earliest from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, and it will bring a trio of powerful instruments to measure the wobbles, quakes and heat that reveal what's going on deep inside the Red Planet — and perhaps offer insight into how Earth formed, as well.

"The goal of InSight is nothing less than to better understand the birth of the Earth, the birth of the planet that we live on," said Bruce Banerdt, InSight's principal investigator at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California. "And we're going to do that by going to Mars, which seems a little bit counterintuitive."

Banerdt spoke during a NASA news conference Thursday (March 29) at JPL to discuss the upcoming mission, which is scheduled to launch between May 5 and June 8, and arrive on Mars Nov. 26. [In Pictures: NASA's InSight Lander to Probe Heart of Mars]

The mission, whose name is short for "Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport," is currently slated launch on May 5 at 4 a.m. PDT (1100 GMT) on United Launch Alliance's Atlas V rocket. That means skywatchers along California's coast, from Santa Maria to San Diego, should be able to see the launch if skies are clear, NASA officials said — and it may be visible farther down the coast as well. (Details for watching the launch in person are online here.)

When InSight arrives at Mars, the spacecraft will spend a dramatic 7 minutes decelerating from 12,500 mph (20,000 km/h) to just 5 mph (8 km/h) before dropping down on the surface, Banerdt said. Then, over a matter of months, it will lower its instruments to the surface to begin its investigation.

"How we get from a ball of featureless rock into a planet that may or may not support life is a key question in planetary science, and these processes that do this all happen in the first tens of millions of years, which is just a few seconds at the beginning of the life of a planet that lasts 4.5 billion years," Banerdt said. "We'd like to be able to understand what happened, and the clues to that are in the structure of the planet that gets set up in these early years."

While Earth is an active planet, with plate tectonics and other processes scrambling its layers, Mars should have a cleaner slate. "Mars is a smaller planet; it's less active than the Earth. And so it has retained the fingerprints of those early processes in its basic structure," Banerdt said. "The thickness of the crust, the composition of the mantle, the size and composition of its core; by mapping out these boundaries, these various different sections of the inside of the planet, we can then understand better how the planet formed and how our planet got to be the way it is."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

What's inside Mars?

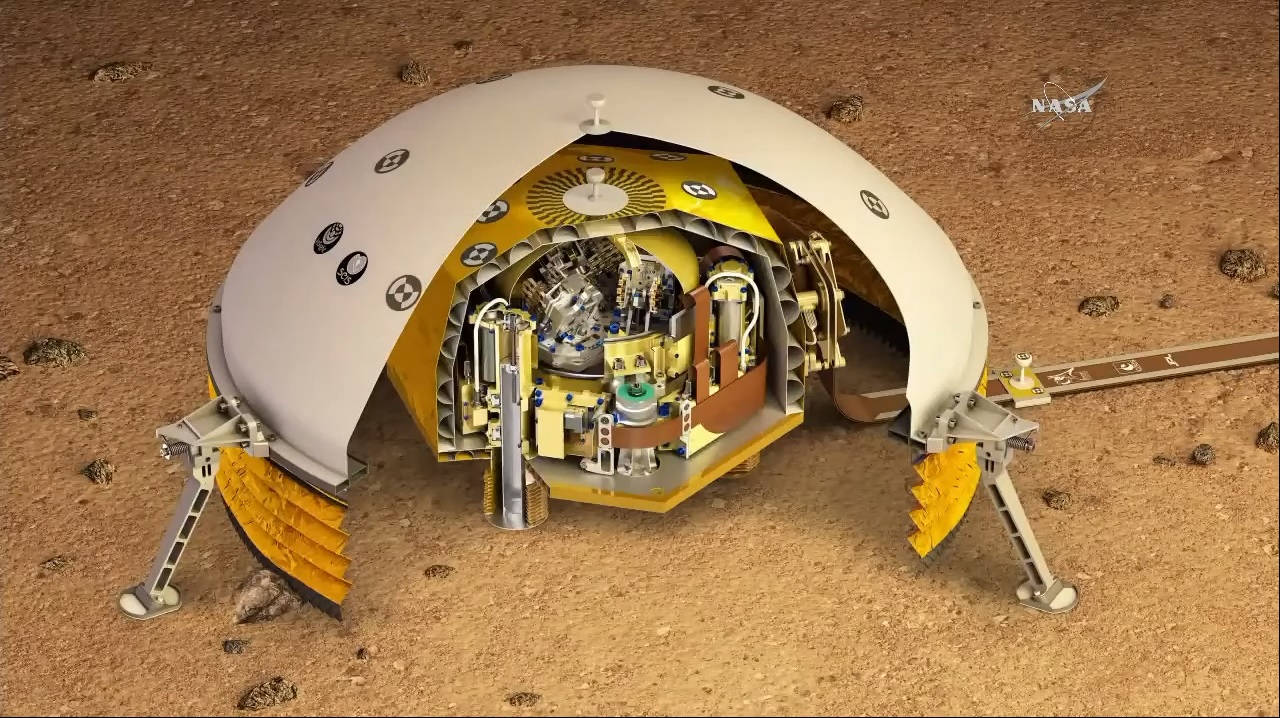

To learn about the early days of the solar system's rocky planets, InSight will need to go deep. Its first key instrument, a seismometer, will measure minuscule "marsquakes" rippling through the planet. Marsquakes generated on the other side of the planet will be distorted by the planet's interior, so scientists can measure them to learn about the composition deep inside. While previous missions, such as the Viking lander, have carried seismometers, none were sensitive enough to pick up these marsquakes, Banerdt said; InSight should be able to precisely measure vibrations with amplitudes as small as an atom.

Apollo astronauts measured moonquakes during their exploration of the lunar surface, and researchers measure earthquakes every day; Banerdt anticipates marsquakes' size and frequency will be somewhere in between.

The next investigation is a radio science experiment. InSight's instrument will be in contact with the Deep Space Network radio dishes on Earth, and by measuring the frequency shift of those communications, researchers can track the instrument's location to an accuracy of within a few inches. As Mars spins, with InSight on its surface, researchers on Earth will be able to measure how the north pole of Mars wobbles over the course of the Martian year. The frequency and size of the wobble will correlate with the Martian core's size and density.

For the third experiment, researchers will use InSight to measure the amount of heat flowing through the planet. Apollo astronauts did something similar by pushing a temperature probe several inches into the moon's surface, measuring slight temperature increases as it descended. Astronauts took less than a half-hour for the measurement, Banerdt said, but the similar robotic operation on Mars will hammer the heat probe down little by little, sending it about a millimeter every 3 seconds. (It'll need about 10,000 of those jolts downward to take the full set of measurements, Banerdt said.) That data will let researchers understand how heat radiates from Mars.

An interplanetary first

The precision and depth of these measurements are a first for Mars, and the mission has another first closer to home: It's the first planetary mission launched from the West Coast, according to Tom Hoffman, InSight project manager at JPL. Because the mission was originally designed for a smaller spacecraft, the Atlas V is powerful enough to lift InSight from either coast — and the West had much less rocket traffic "congestion," Hoffman said at the news conference.

"Depending on where you are in Southern California, you'll be able to see the spacecraft at various points along its ascent as it heads off on its way to Mars," he added. "This should be quite spectacular because it is an early morning hour, so it should light up the sky and be very visible throughout pretty much all of Southern California, even down into Mexico… If you happen to be up and [with] nothing better to do at four in the morning, please take a look out your back window."

Once the lander reaches the Martian surface on Nov. 26, it will have a very important first task.

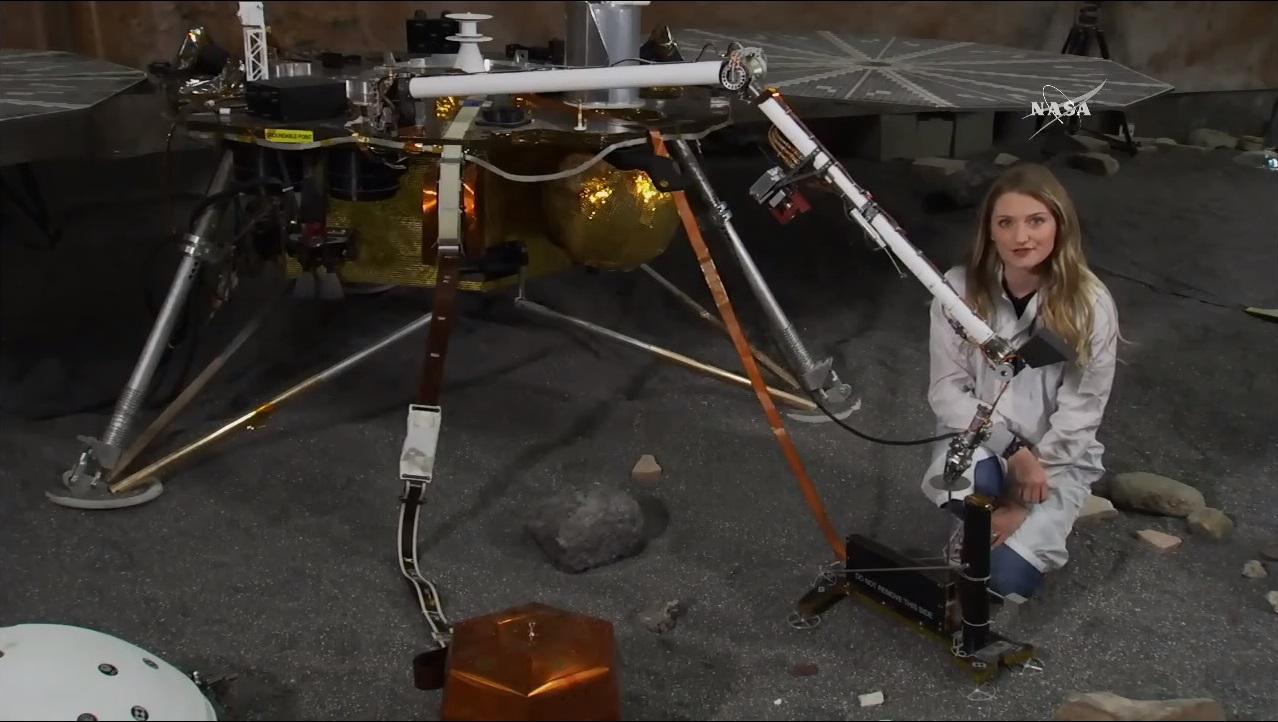

"InSight's going to land on a new place on Mars that none of us have seen from the surface before, so like any tourist, we're going to want to take some pictures," Jaime Singer, InSight instrument deployment lead at JPL, said remotely from a simulated Martian environment at JPL, where she demonstrated how the instruments will deploy. "InSight has two cameras for that purpose. [A] camera on the body of the lander will take the first image that we get back from Mars." Researchers will use that image, which should be available the day the spacecraft lands, to get the lay of the land before deploying its instruments.

The researchers are clearly in high spirits as the launch date approaches, getting ready for an exciting landing process and priceless data about the interior of the solar system's rocky planets.

"The first time we get a marsquake down on the surface, I think I'm going to be dancing around the room," Banerdt said. There was a seismometer on Viking, which landed when he was in graduate school, but it wasn't sensitive enough to detect any seismic data. "Over my career, there's all these questions I had about Mars that could only really be answered with a seismometer," he said. "And so when we see that first quake, that's the final — underlined, bold type — this is actually going to work, and we're going to start getting the kind of detailed information about the inside of Mars that we've been waiting for for 40, 50 years."

"I'm not sure how I feel about you dancing — I've seen you dance before," Hoffman joked.

InSight carries instruments and instrument components from several European partners; France's Centre National d'Études Spatiales led the team that built the ultrasensitive seismometer, and the German Aerospace Center developed the thermal probe, NASA officials said in a statement.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.