Chinese Space Station Could Crash to Earth Late Sunday or Early Monday

Quiet solar activity has once again pushed back the re-entry time for a China's falling space station, Tiangong-1, according to the European Space Agency (ESA) and U.S.-based analysis group Aerospace Corp.

The doomed Tiangong-1 is now expected to fall to Earth around 7:25 p.m. EDT (2325 GMT) on Sunday (April 1), with a window that could stretch into early Monday, officials with ESA's Space Debris Office said in an update this morning (March 31). As of 5 p.m. EDT today, Aerospace Corp., which is also tracking Tiangong-1, predicts Tiangong-1 will crash at 7:53 p.m. EDT (2353 GMT) Sunday, give or take 7 hours. [Track Tiangong-1! Use This Satellite Tracker]

Current predictions for Tiangong-1 show that the station may fall somewhere around Africa, although that area remains highly uncertain. Even a change in time of a minute will alter the predicted debris track by hundreds of miles, cautioned Aerospace Corp. Not only that, Tiangong-1's re-entry time is becoming more delayed and the station may actually enter on April 2, depending on the sun's activity and the station's tumble.

"The predictions are getting farther and farther into the future," Andrew Abraham, a senior member of the technical staff at Aerospace Corp, told Space.com in an interview today. "We're going to keep it [the Aerospace Corp. website] updated basically as frequently as we get the data, which varies. The sensors aren't evenly distributed across the globe. Sometimes we get more data, and sometimes periods where there's not as much data."

Most of the United States appeared to be in the clear at that time, except for one orbital track that moves over California northeast towards Texas. Again, Abraham cautioned, this information is subject to change as predictions are updated.

The time for Tiangong-1's uncontrolled descent remains highly uncertain, in large part due to how quiet the sun has been. If the sun is active, its energy pushes more strongly against Earth's atmosphere. The atmosphere then balloons and becomes denser at higher altitudes. The density of the atmosphere affects the drag against Tiangong-1's orbital speed. As Tiangong-1 loses energy due to drag, it falls towards Earth.

"The space debris team at ESA have adapted their reentry forecast over the last 24 hours to take into consideration the conditions of low solar activity. New data received overnight gave further confirmation that the forecast window is moving to later on 1 April," ESA officials said in an update from 5 a.m. EDT (0900 GMT).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The team now are forecasting a window centered around 23:25 UTC on 1 April (01:25 CEST 2 April), and running from the afternoon of 1 April to the early morning on 2 April. This remains highly variable."

Tiangong-1's predicted re-entry time has been adjusted repeatedly in recent days because the sun was quieter than predicted, ESA added. "A high-speed stream of particles from the sun, which was expected to reach Earth and influence our planet’s geomagnetic field, did, in fact, not have any effect, and calmer space weather around Earth and its atmosphere is now expected in the coming days," it stated.

Another factor is the cross-sectional area that Tiangong-1 is presenting to the Earth's atmosphere as it tumbles, Abraham said. The area seems to be lessening as time goes on, but the reasons are unclear. "The direction of the axis that is tumbling could be changing, or the amount of tumble could be changing, or both. I don't know what the answer is right now," he said.

China launched Tiangong-1 in 2011and remained active for five years, hosting two astronaut crews and one uncrewed docking mission. China's Manned Space Engineering Office, which oversees the country's human spaceflight missions, lost contact with the station in 2016. Since then, the 9.4-ton (8.5-metric ton) module has been falling naturally towards Earth.

In 2016, China launched a successor space station, called Tiangong-2, which remains active today.

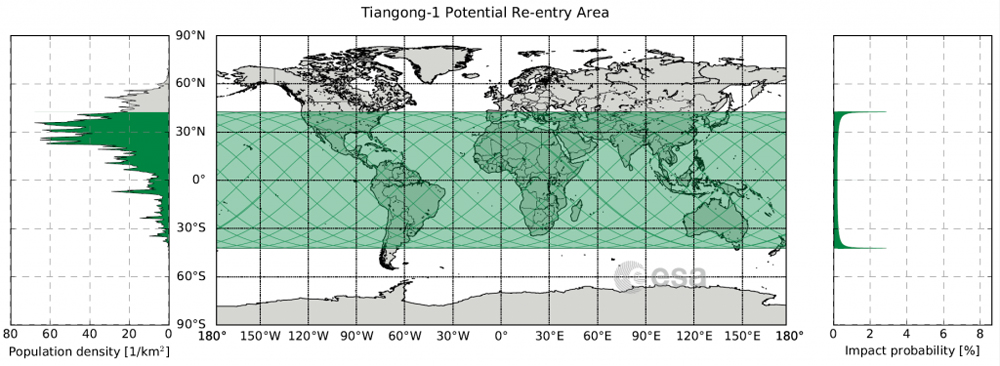

Tiangong-1 orbits Earth with an inclination between 43 degrees north and 43 degrees south latitudes, so theoretically it could fall under any location on that path. That swath of geographical expanse includes much of the populated world, including the United States.

The chances, however, of any one location being hit are infinitesimally small, even worse than winning the Powerball jackpot. While Tiangong-1 will likely generate spectacular fireballsduring its descent, Harvard University astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell predicts only 220 to 440 lbs. (100 to 200 kg) will make it through to the surface.

Debris from space sometimes causes interesting falls on Earth's surface. The most famous example was NASA's Skylab space station in 1979, which unexpectedly threw pieces into rural Australia after the agency tried to steer it towards the ocean.

Editor's note: This story was updated at 5:35 p.m. EDT with the latest information on the Tiangong-1 space station's re-entry forecast.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.