SAN FRANCISCO — If music really is a universal language, as is so often and so blithely claimed, we can use it to make some long-sought cosmic connections.

That's the idea behind Intergalactic Omniphonics, a new art project by experimental philosopher Jonathon Keats that aims to catch E.T.'s ear.

Or whatever organ may allow aliens to rock out. It's quite provincial to assume that our nebular neighbors access and appreciate music — which is basically just the modulation of frequency and amplitude over time — in the same way that we do. [Alien Thinking: The Conceptual Space Art of Jonathon Keats]

So Intergalactic Omniphonics — a partnership with the music department at the University of North Carolina-Asheville, where Keats recently worked on a fellowship — features instruments across an impressive gamut.

Take its two "gamma-ray bells," for example. Keats bought a uranium-glass marble and a radium watch dial on eBay, then encased this gear in protective lead. When a bell's wooden handle is lifted, the radioactive innards are exposed, sending high-energy gamma-rays out into the cosmos.

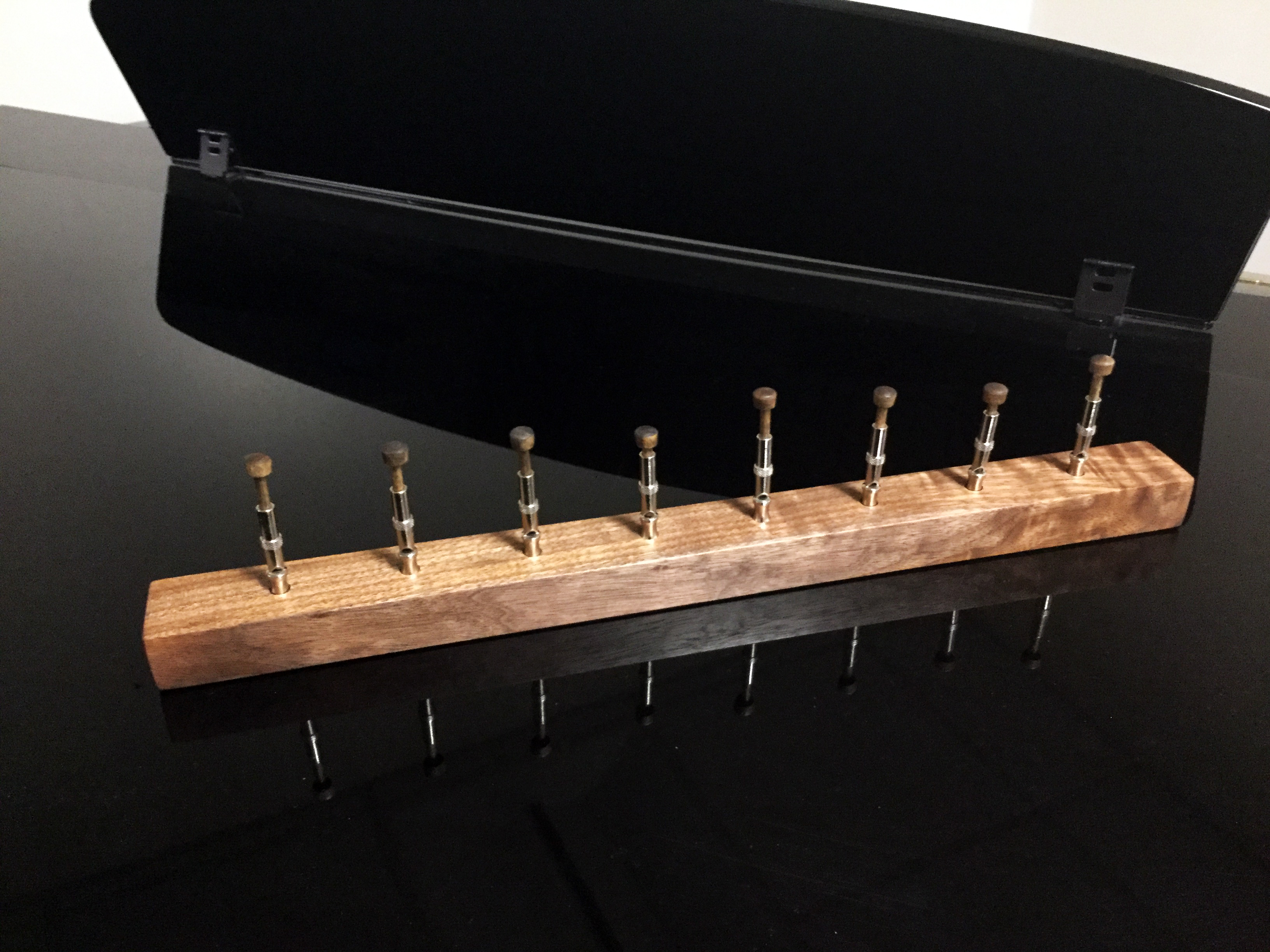

Keats' eBay haul also included a selection of dog whistles, which he assembled into an "ultrasonic organ." While this instrument's high-pitch stylings are beyond the reach of human ears, they can be appreciated by man's best friend and an assortment of other Earth creatures.

Then there's the "gravitational cello," which consists of a steel ball hanging from a string at the end of a wooden shaft. The musician swings this ball, generating gravitational waves — the ripples in space-time first predicted by Albert Einstein in 1916 and finally detected directly for the first time in 2015, after a merger between two black holes.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Gravitational waves are created by the acceleration of any object with mass, so a musician doesn't necessarily need something as fancy as a cello. (Indeed, the cellist must keep his or her body as still as possible during a performance, for body movements generate their own gravitational waves that could swamp the beautiful music being made.) So, Keats also created "gravitational rattles," which even tin-eared babies can play.

"Just put a rock in your hand and you can make gravitational music," Keats told Space.com.

If you live in the Bay Area, you can see these and other instruments up close tonight (July 24): Modernism Gallery in downtown San Francisco is hosting a launch event for Intergalactic Omniphonics from 5:30 p.m. to 8 p.m. local time.

The project isn't solely dedicated to getting E.T. out of the shadows and onto the dance floor. It's also an attempt to forge greater common ground here on Earth, where different cultures and different communities can seem very alien to each other.

"What we're really lacking in society is a way to connect across borders and boundaries," Keats said. "We need to bring about a fundamental paradigm shift in how we think about ourselves."

Keats tried to effect such a shift a few years back with his "First Copernican Art Manifesto," which pushed writers, painters and other creative types to embrace the principle of mediocrity, as astronomers have done.

"It failed miserably, and that's why I'm here," Keats said, noting that artists are still chasing masterpieces. Intergalactic Omniphonics is at heart another bite at the apple, he added: "I can infiltrate society by making music."

The infiltration plan includes a "universal anthem." The anthem is based on something that is indeed universal, as far as we can tell — the second law of thermodynamics, which holds that the total entropy (or disorder) of an isolated system can never go down over time.

Life can be thought of as a fight against entropy, Keats said — a fight that every organism loses, eventually, when it dies. The universal anthem is a representation of this struggle: A solo plays against an orchestral backdrop, its tune getting more and more structured over time, until it's snuffed out in the ultimate silence of death. (The orchestra's sound, meanwhile, gets less and less ordered until the solo drops off.)

Intergalactic Omniphonics plans to distribute the basic framework (though not the specifics, which are open to interpretation) of the universal anthem free, via a Creative Commons license. Keats hopes the music makes its way onto non-ultrasonic organs and other traditional human instruments all over the world.

"This should be at ball games," he said. "The anthem should be everywhere."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.