Apollo Spacesuits Survive Today — in the Roofs Over Your Head

When the Apollo astronauts launched into space, they wore spacesuits specially designed to protect them from many of the hazards they faced. Although astronauts these days wear different garb than the space explorers from 50 years ago, the Apollo material can be found across the Earth today. But don't look for it in your local clothing store; material based on spacesuit design has been lifted to new heights, serving as protective roofs for an array of popular buildings.

In 1956, aeronautical engineer Walter Bird founded Birdair Structures Inc. out of his kitchen in Buffalo, New York. His initial focus was on a material known as "Beta cloth," a durable, lightweight, noncombustable material developed for astronaut wear.

"As far as the material, not much has changed," Brian Dentinger, Birdair's director of quality, told Space.com in an email. "It is still Teflon-coated fiberglass." [Spacesuit Suite: Evolution of Cosmic Clothes (Infographic)]

That veneer is what made the fabric stand out. "The Teflon coating on fiberglass yarns does not break down [when struck] by harmful [ultraviolet] rays," Dentinger said. "This is one of the main reasons the material was used in the space program."

A safer spacesuit

In 1967, a flash fire in the Apollo 1 command module during a test exercise killed all three astronauts. As part of the resulting safety efforts, NASA engineers searched for ways to improve the safety of the spacesuits worn by the astronauts. The Ohio-based Owens-Corning Fiberglass, working with Delaware's DuPont,, proposed a Beta cloth. After twisting ultrafine glass filaments into threads and weaving them into fabric, the manufacturers coated the material with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), a material invented by DuPont and more commonly known as Teflon.

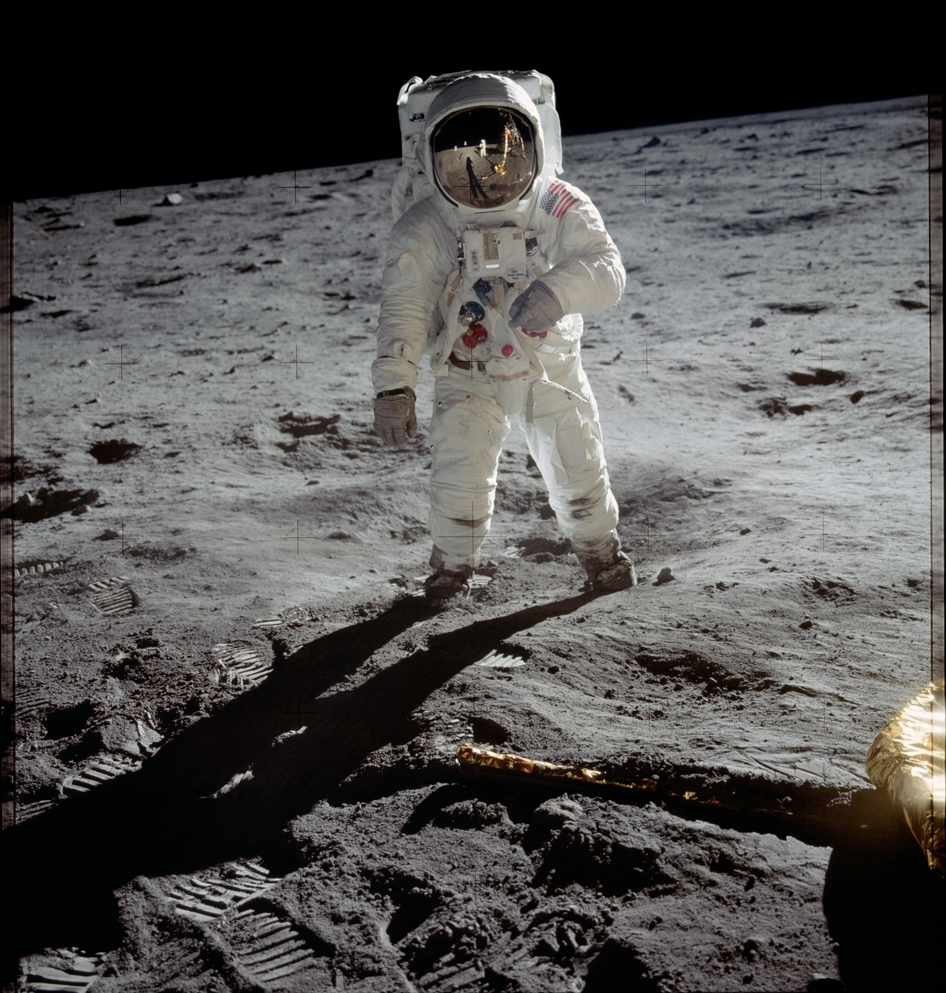

With a melting point of over 650 degrees Fahrenheit (340 degrees Celsius), Beta cloth proved noncombustible and durable enough to meet NASA's needs. The newborn space agency incorporated the new material into the outer protective layers of the Integrated Thermal Micrometeoroid Garment for the A7L spacesuits worn by Apollo and Skylab astronauts. Not only did the new material provide the astronauts with thermal and UV protection, but it also shielded them from the abrasive moon dust encountered during lunar landings.

Today, NASA's astronauts wear suits made of Ortho-Fabric rather than the fiberglass fabric of the Apollo era. But Beta cloth still appears in space, commonly employed as the outer layer of multilayer insulation blankets. According to Bron Aerotech, Beta cloth was heavily used on the space shuttle and continues to protect the interior and exterior of the International Space Station. The cloth is even on Mars, protecting the Curiosity rover's nuclear power plant, according to Bron.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

From space to Earth

Enter Bird, formerly an engineer at Bell Aeronautics. After founding Birdair Structures, he developed ways to use the spacesuit material in removable covers for sports buildings. In 1957, Bird's home was featured on the cover of Life magazine, with an air-supported pool enclosure protecting swimmers from the winter cold.

Fabric tension structures have different classifications. Air-supported structures derive their structural integrity from the use of pressurized air to inflate the fabric, while tension-supported or tension-membrane structures rely on cables or steel framing for their support.

Birdair collaborated with other companies for Expo '70 in Osaka, Japan, to develop an air-supported, vinyl-coated fiberglass-fabric roof, the first of its kind. The fabric created for this roof, a material later called Sheerfill architectural membrane, expanded the market in the field of lightweight roof structures, according to NASA.

The same qualities that make Beta cloth appealing for spacesuits also make it ideal for permanent structures. The PTFE fiberglass fabric is, pound-for-pound, stronger than steel while weighing less than 5 ounces per square foot (1.53 kg per square meter). It lets in natural light while keeping out heat, making it an energy-efficient roofing alternative. Its durability and low-maintenance characteristics make it cost-effective.

In 1973, La Verne College in La Verne, California, contracted with Birdair to build the world's first permanent roof system that used a PTFE fiberglass membrane; Birdair made the roof for La Verne's Sports Science and Athletics Pavilion. Known to students as "the Super Tents" due to its quirky design, the roof remains standing after 45 years.

"We had such needs as a new gymnasium and locker facility, an art studio, theater, recreation areas and [a] snack bar for our students, a student health center, and a workout area," Stephan Morgan told La Verne Magazine in 2017. Morgan, later president of the university, was at the time the building project manager and assistant to then-President Leland Newcomer. "As we started to explore meeting these needs, we realized the cost of building traditional facilities was beyond our modest financial capacity," he said. The total cost of the project was $2.5 million.

Being the first to test a new material didn't come without risks.

"This was the first one made, so no one knew what was going to happen; as a result, the builders could not give any major warranty guarantees on their fabric beyond 20 years," Al Clark, La Verne professor of humanities, told La Verne Magazine.

Morgan and the current college president discussed the materials' reliability.

"At the time we built the facility, no one was quite sure how long the roof would last," Morgan said. "Some said, maybe 20 years, some said longer." Discussing the longevity of the room with then-President Newcomer, they joked that neither of them would be around in 20 years, not knowing Morgan would be the president and responsible if the roof failed.

Thankfully, it didn't. The new material proved sturdy and remains functioning 45 years after the roof was constructed.

Since then, Birdair has gone on to build a variety of other structures. When a tornado ripped through downtown Atlanta in March 2008 and passed within about 100 yards (90 meters) of Atlanta’s Georgia Dome , Beta cloth covered the building, protecting the fans inside. Classified as an EF2 tornado, the storm brought winds in excess of 100 mph (160 km/h).

"It sounded like a freight train," game attendee Tyler Williams told ESPN. "The rafters were swaying, and the roof of the dome was starting to ripple.

"It was a little frightening, to say the least."

None of the 18,000 fans who had gathered inside the dome for a college basketball game at the time of the tornado were injured, although the storm ripped a hole in the roof of the building. Less than 12 hours after the storm hit, Birdair crewmembers were on-site to evaluate the extent of the damage, according to the company.

The Georgia Dome housed basketball, gymnastics and handball during the 1996 Summer Olympics. In 2017, the Georgia Dome was demolished. Its replacement, the Mercedes-Benz Stadium, boasts a retractable petal roof supported by Birdair’s fabric, though it is coated with ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE) rather than PTFE. ETFE has a higher tensile strength and is more heat-resistant.

Spacesuit-inspired roofs can be found around the world, not just in the U.S. In 1981, Birdair completed Saudi Arabia's Haj Terminal, still standing as one of the largest tensile membrane structures in the world. Other projects include the La Plata Stadium in Argentina, three of the four primary stadiums for the 2010 World Cup in South Africa and the Sony Center in Germany. The Reliant Stadium in Houston also boasts a PTFE roof, the first retractable roof in the NFL, according to NASA.

"Based on the long life cycle and the iconic structures all over the world, we feel this product will still be in use decades from now," Dentinger said.

So, as astronauts' spacesuits get more advanced, this Apollo-era technology will continue to shelter humans back on Earth.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky