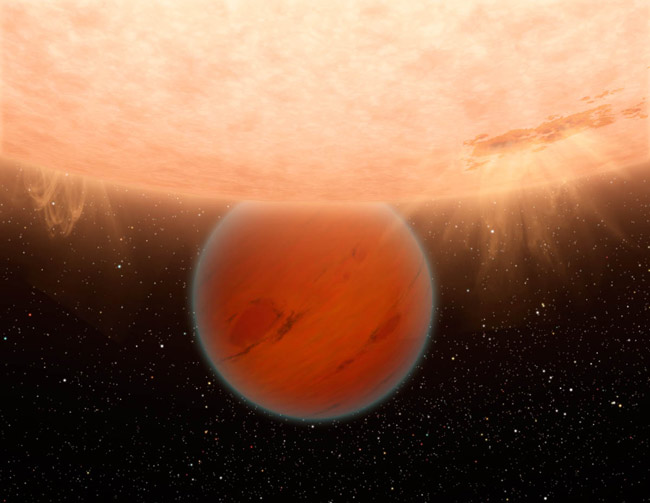

Alien Planet Has Pretty Weird Atmosphere

A Neptune-sized planet orbiting another star has one oddatmosphere ? analysis has shown that it lacks methane, a common ingredient for manyplanets in our solar system and a possible signature of life.

The discovery was made after NASA's SpitzerSpace Telescope captured the extrasolar planet's light in six infraredwavelengths, allowing researchers to analyze the components of the exoplanet'satmosphere.

The results are puzzling because existing models suggestthat carbon present in the exoplanetshould be in the form of methane, said study lead author Kevin Stevenson, a Ph.D.student at the University of Central Florida in Orlando.

"The observations are quite telling," Stevensontold SPACE.com. "The ball is in the theorists' court now. They will have toimprove their models, taking into account the disequilibrium processes thatcould account for what is happening. The current models are a very good firststep in determining the atmospheres of these planets, but now we need to go astep further."

Methane in our solar system

The hot, methane-free planet, called GJ 436b, is about thesize of Neptune, making it the smallestalien planet whose atmosphere has been successfully analyzed by any telescope.The smallest-known exoplanet today is a distant, rocky world called Gliese 581e about 20.5 light-years from Earth.

GJ 436b is located 33 light-years away in the constellationLeo, the Lion. The planet rides in a tight, 2.64-day orbit around its small star,an "M-dwarf" class star that is much cooler than our sun. The planetcan be viewed from Earth as it crosses in front of its star.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The study's findings will help move astronomers one stepcloser to probing and characterizing the atmospheres of distant planets thesize of Earth.

Eventually, a larger space telescope could use the same kindof technique to search smaller, Earth-like worlds for methane and otherchemical signs of life, such as water, oxygen and carbon dioxide.

"Ultimately, we want to find biosignatures on a small,rocky world," Stevenson said. "Oxygen, especially with even a littlemethane, would tell us that we humans might not be alone."

All of the giantplanets in our solar system have methane in their atmospheres. On Earth,methane is manufactured primarily by microbes living in cows and soaking inwaterlogged rice fields.

Neptune is blue because of this chemical, which absorbs redlight. Methane is a common ingredient of relatively cool bodies, including browndwarfs, which are cool, dim substars.

In fact, any planet with the common atmospheric mix ofhydrogen, carbon and oxygen, and a temperature of up to 1,340 degreesFahrenheit (727 degrees Celsius) is expected to have a large amount of methaneand a small amount of carbon monoxide. That's because under these temperatures,any carbon present should be chemically favored to be in the form of methane.

?"A lot of the larger planets and brown dwarfs arethought to have similar atmospheric behavior," said Joseph Harrington, anassociate professor at the University of Central Florida and the study'sprincipal investigator. "Brown dwarfs pretty much all follow a fairlystraight-forward atmospheric chemistry that is not difficult to predict. Manytheorists have applied these models to hot exoplanets, but in this case itdoesn't work."

Methane-free

With a temperature of 980 degrees Fahrenheit (527 degreesCelsius), GJ 436b should have abundant methane and less carbon monoxide. Yet,Spitzer observations have detected the opposite.

The infrared wavelengths captured by the space telescopeshow evidence for carbon monoxide but not methane.

"What this does tell us is that there is room forimprovement in our models," Harrington explained. "The lesson here isthat planets really do have individual personalities."

Spitzer was able to detect the faint glow of GJ 436b bywatching it slip behind its star, an event that is known as a secondaryeclipse.

As the planet disappears from sight, the total lightobserved from the star system drops ? this reduction is measured to find thebrightness of the planet at various wavelengths. This technique was firstpioneered by Spitzer in 2005 and has since been used to measure the atmosphericcomponents of several Jupiter-sized exoplanets, or so-called "hotJupiters."

"The Spitzer technique is being pushed to smaller,cooler planets more like our Earth than the previously studied hotJupiters," said Charles Beichman, director of NASA's Exoplanet ScienceInstitute at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the California Institute of Technology,both located in Pasadena, Calif.

"In coming years, we can expect that a space telescopecould characterize the atmosphere of a rocky planet a few times the size of theEarth. Such a planet might show signposts of life," he added.

This research was performed before Spitzer ran out of itsliquid coolant in May 2009, officially beginning its "warm"mission.

The details of the study will be published in the April 22issue of the journal Nature.

- Images- The Strangest Alien Planets

- Top10 Extreme Planet Facts

- The MostIntriguing Extrasolar Planets

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.