Saturn's Moon Triggers Giant Snowballs in Planet's Ring

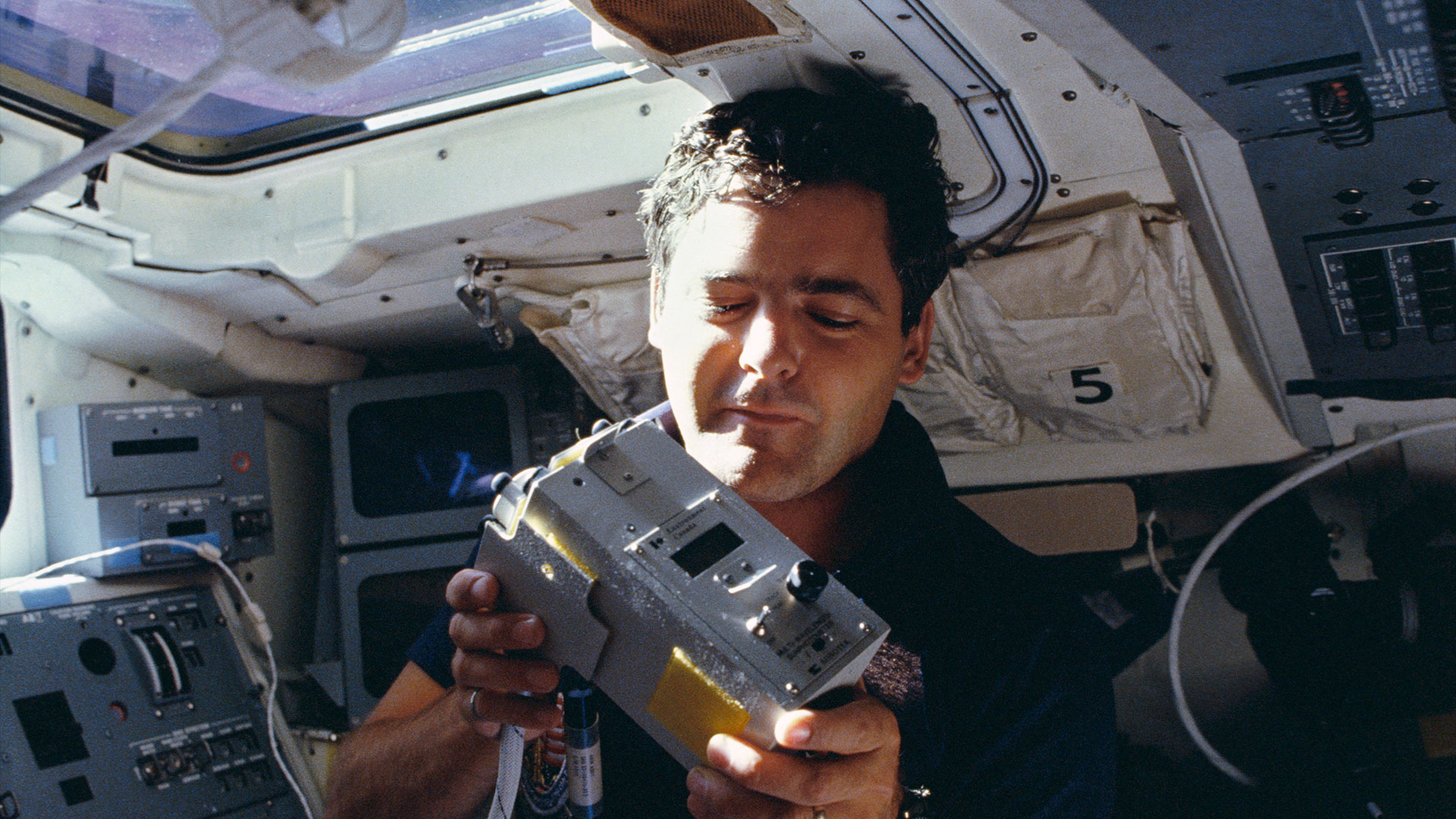

ANASA spacecraft that orbits Saturn has captured new images that show icyparticles in the planet's outermost discrete ring that are clumping into giantsnowballs, created by the gravitational pull of a nearby moon.

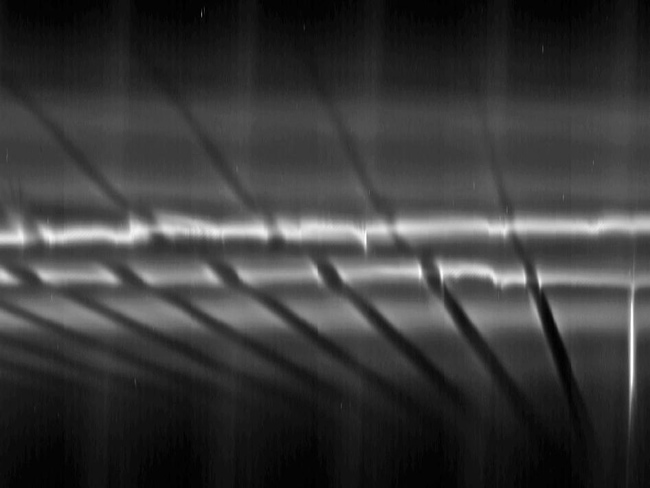

TheCassini spacecraft, which has monitored collisions and disturbances in the gas giant'srings for the last six years, spotted the icy clumping process as the moonPrometheus makes multiple swings by Saturn's F ring ? a thin ring orbitingabout 87,000 miles (140,000 km) out from the planet. [ Photo of the fan-like structures].

Themoon's gravitational pull creates disturbances in the ring material, makingwake channels that trigger the formation of objects as large as 12 miles (20kilometers) in diameter, when smaller masses stick together through theirmutual gravitational attraction.

Thenatural processes that occur within Saturn's ringscan give scientists a glimpse into the mechanisms at work in our early solarsystem, as planets and moons coalesced out of disks of debris.

"Scientistshave never seen objects actually form before," said Carl Murray, a Cassiniimaging team member based at Queen Mary, University of London. "We nowhave direct evidence of that process and the rowdy dance between the moons andbits of space debris."

Murraypresented the study July 20 at the Committee on Space Research meeting inBremen, Germany. The findings were also published July 14 in the online editionof the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Saturn'sF ring

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Saturn'srelatively thin F ring was discovered by NASA's Pioneer 11 spacecraft in 1979. Prometheusand Pandora, the small moons found on either flank of the F ring, werediscovered a year later by NASA's Voyager 1 robotic space probe.

Inthe years since its discovery, the F ring has undergone constant changes inappearance, and scientists have closely monitored the behavior of the twomischievous moons for answers.

Prometheus,which is larger and closer to Saturn, appears to be the main source of the disturbances in the F ring. At its longest point, the potato-shaped moon is 92miles (148 km) across.

Thismoon swerves around Saturn at a speed slightly greater than the speed of themuch smaller particles in the planet's F ring. As a result of this discrepancy,and the slightly offset orientation of Prometheus' orbit, the moon laps the Fring particles, stirring them up approximately every 68 days.

"Someof these objects will get ripped apart the next time Prometheus whipsaround," Murray said. "But some escape. Every time they survive anencounter, they can grow and become more and more stable."

Cassiniscientists previously used the spacecraft's ultraviolet imaging spectrograph todetect thickened blobs of material near the F ring, after noticing starlightwas partially blocked in that area. These objects may be related to thesnowball-like clumps that were discovered by Murray and his colleagues.

Densityand life span

Thenewly-found objects in the F ring also appear dense enough to possess whatscientists call "self-gravity." This means that they can attract moreparticles and accumulate in size as ring particles bounce around in Prometheus'wake, Murray said.

Asa result, the giant clumps could be almost as dense as Prometheus itself, butonly about one-fourteenth as dense as Earth in comparison.

Thesesnowballs in the F ring also have a higher chance of survival due to theirserendipitous location in the Saturn system. The F ring is located at a pointthat is balanced between the tidal force of Saturn trying to break objectsapart, and the self-gravity that pulls objects together.

Still,these giant snowballs have short life spans, likely forming and breaking apartwithin a few months.

Thenew study could also help scientists explain the origin of a mysterious objectdiscovered by Cassini scientists in 2004. The object, which has beenprovisionally named S/2004 S 6is about 3 to 6 miles (5 to 10 km) in diameter, and occasionally bumps intoSaturn's F ring, producing jets of debris in the process.

"Thenew analysis fills in some blanks in our solar system's history, giving usclues about how it transformed from floating bits of dust to densebodies," said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA's JetPropulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "The F ring peels back some ofthe mystery and continues to surprise us."

- Gallery - The Rings and Moons of Saturn

- Cassini's Greatest Hits: Images of Saturn

- Giant Propellers Discovered In Saturn's Rings

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.