The Event Horizon Telescope Is Trying to Take the First-Ever Photo of a Black Hole

Snapping a black hole's silhouette is like photographing an orange on the moon.

Astronomers orchestrated radio dish telescopes across the world into an Earth-size virtual camera for a bold new experiment attempting to deliver the first-ever image of a black hole. The telescope collaboration is set to make a big announcement of results this week, and members also described their research approach at a talk in March.

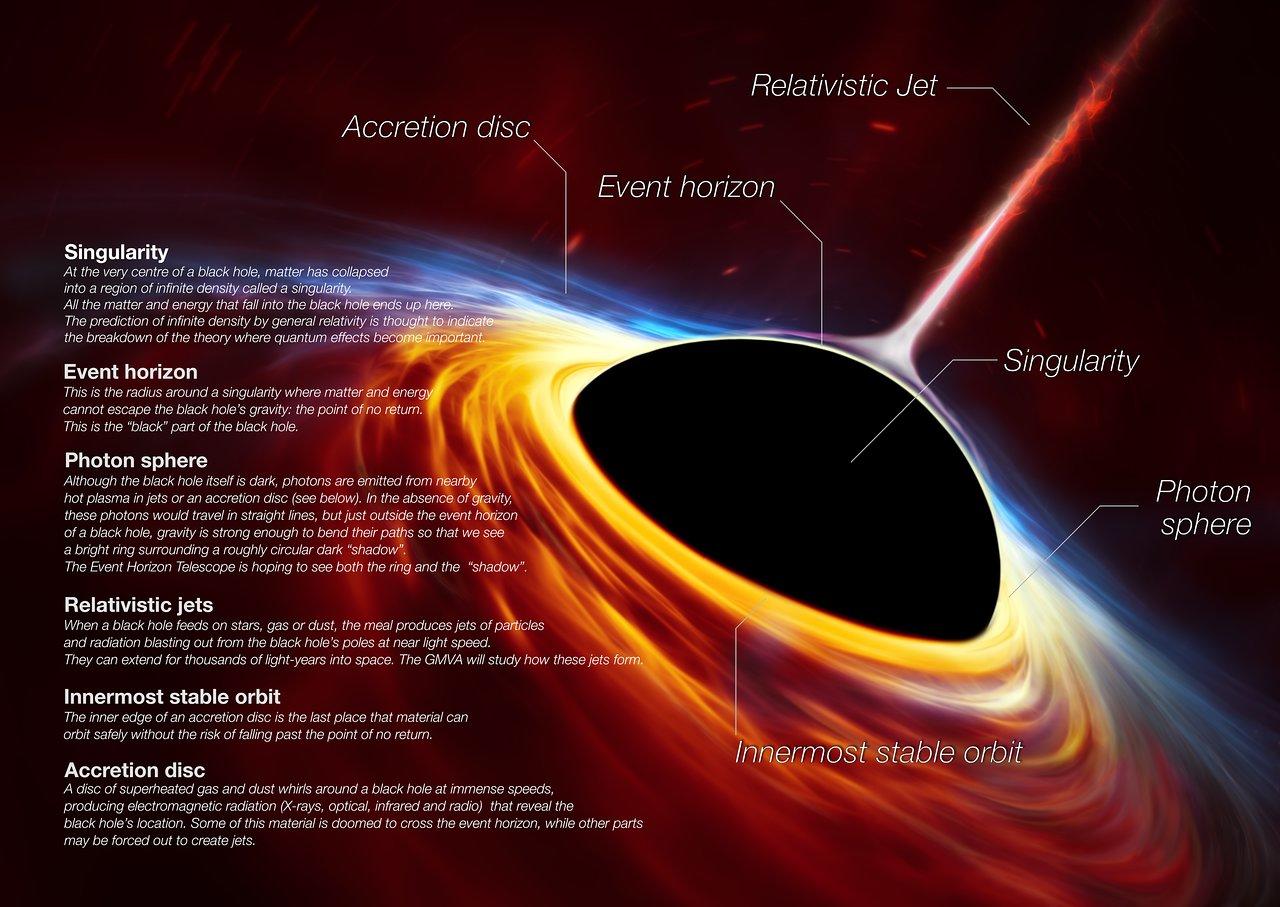

Black holes are extreme warps in space-time that are so strong, their massive gravity doesn't even let light escape once it gets close enough.

The astronomers' idea is to photograph the circular opaque silhouette of a black hole cast on a bright background. The shadow's edge is the event horizon, a black hole's point of no return. A picture is worth a thousand words, and a photograph of a black hole would be an important tool for understanding astrophysics, cosmology and the role of black holes in the universe.

Related: 'Groundbreaking Result' Coming from Black-Hole Hunting Event Horizon Telescope

If an astronaut laid an orange on the surface of the moon, the citrus fruit would be very difficult to view from Earth. Black holes are just as hard to spot, said Sheperd Doeleman, the project director of an ambitious new project called the Event Horizon Telescope.

Doeleman shared this anecdote with an audience at a panel at the South by Southwest (SXSW) festival in Austin, Texas, last month. Doeleman and fellow collaborators Sera Markoff, Peter Galison and Dimitrios Psaltis illuminated how the project works during the SXSW event, "EHT: A Planetary Effort to Photograph a Black Hole."

Black holes are massive structures when compared to planets and humans. But what seems large to us, is, on a galactic scale, teeny-tiny. So photographing a black hole's event horizon complicated.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"One of the EHT targets is about 10 percent of the size of our solar system," Sera Markoff, an astrophysicist from the University of Amsterdam, said during the panel. The supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, called Sagittarius A*, is about the size of the orbit of Mercury, Doeleman added.

If a spaceship could zip astronomers out of the Milky Way, which is about 50 billion times bigger than Sagittarius A*, according to Markoff, then spotting this black hole among the billions of other stars and planets in the galaxy would be quite tricky.

To observe the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, or to view another of the project's targets — the supermassive black hole at the core of the supergiant elliptical galaxy Messier 87 — the EHT team had to turn Earth into a virtual telescope platform. That's because the power of a telescope to resolve images is limited to the size of its dish, and by using an array of instruments across the world, the team is effectively breaking up the dish and scattering the pieces globally to make one big space eye.

Related: This Huge Black Hole Is Spinning at Half the Speed of Light!

The radio telescope observatories involved in EHT's 2017 observations were ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile; APEX (Atacama Pathfinder Experiment) in Chile; IRAM 30m (Institut de RadioAstronomie Millimétrique) in Spain; LMT (Large Millimeter Telescope) in Mexico; SMT (Submillimeter Telescope) in Arizona; JCMT (James Clerk Maxwell Telescope) in Hawaii; SMA (SubMillimeter Array) in Hawaii; and SPT (South Pole Telescope) in Antarctica.

Coordinated observations were also made in the X-ray and gamma-ray bands.

Sagittarius A* is dormant, which means it doesn't actively consume a lot of nearby stars and gas, releasing radiation. An active black hole lurks inside Messier 87. To view the neighborhood supermassive black hole and the one churning farther away, the telescopes need to observe "the entire range of the electromagnetic spectrum, from the radio up to the gamma rays," Markoff said.

Was Einstein 100% right?

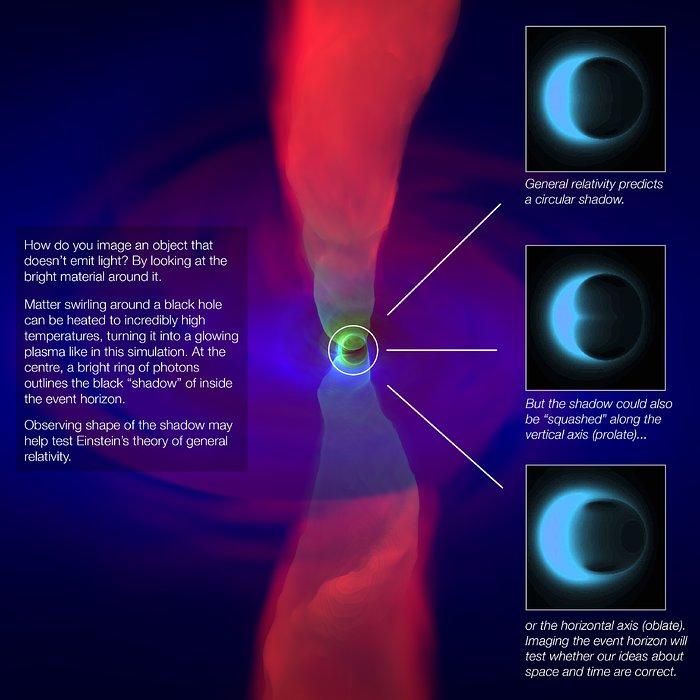

At the project's core, its 200 scientists want to answer two questions, according to Psaltis, an astronomer and physicist at the University of Arizona. The first is simply if photographing a black hole is possible. But the second important thing they ask is if Einstein was 100 percent right about how black holes behave.

"Einstein told us 100 years ago exactly what the size and the shape of that [black hole's] shadow should be. If we could lay a ruler across that shadow, we'd be able to test Einstein's theory of the black hole boundary," Doeleman said.

The team also wanted to build models that would describe black holes in various circumstances, which will then be compared to EHT observations.

In the work described at SXSW, the team used graphics processing units (GPUs), like the ones used in your favorite video game consoles or your computer, to model all the hypothetical varieties of a black hole environment. They produced hundreds of gigabytes of 3D volume data to model the possibilities. Psaltis said photons, plasma, gas and magnetic fields are all described in a black hole's forecast.

Once they get one, the team can compare an image of a black hole's shadow to the different scenarios processed by the GPUs in order to make the most realistic simulation of how a black hole behaves, based on our current understanding of physics.

"What the black hole image could do for us, if we can get it, would be to take something that is the most extreme, the strangest prediction of general relativity, one of the great accomplishments of the human mind, [and] combine it with the most advanced electronics with a planetary scale collaboration with the most advanced statistics [and] new imaging techniques," Galison, a professor at Harvard University, said during the panel. "It's like making a new camera with a new kind of film, a new kind of lens, combining it with other cameras, all at once, and if that could happen, if we could actually get in and see right up close to the horizon."

Galison added that the first picture of a black hole would prove, beyond a shadow of a doubt — pun intended — that these gargantuan, mighty and elusive structures do exist.

- Mysterious 'Cow' Blast in Space May Reveal Birth of a Black Hole

- This Trippy Simulation Shows How Monster Black Holes Glow Before They Collide

- Rarely Seen Middleweight Black Hole Gobbles Star

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.