What's Eating Mars' Methane? ExoMars Results Deepen Mystery

This key element is missing.

Scientists have been puzzling over the presence of methane on Mars for years.

The gas has been detected previously on the Red Planet. Because much of the methane on Earth has a biological origin, scientists have been tantalized by the prospect that methane on Mars could come from living organisms, too.

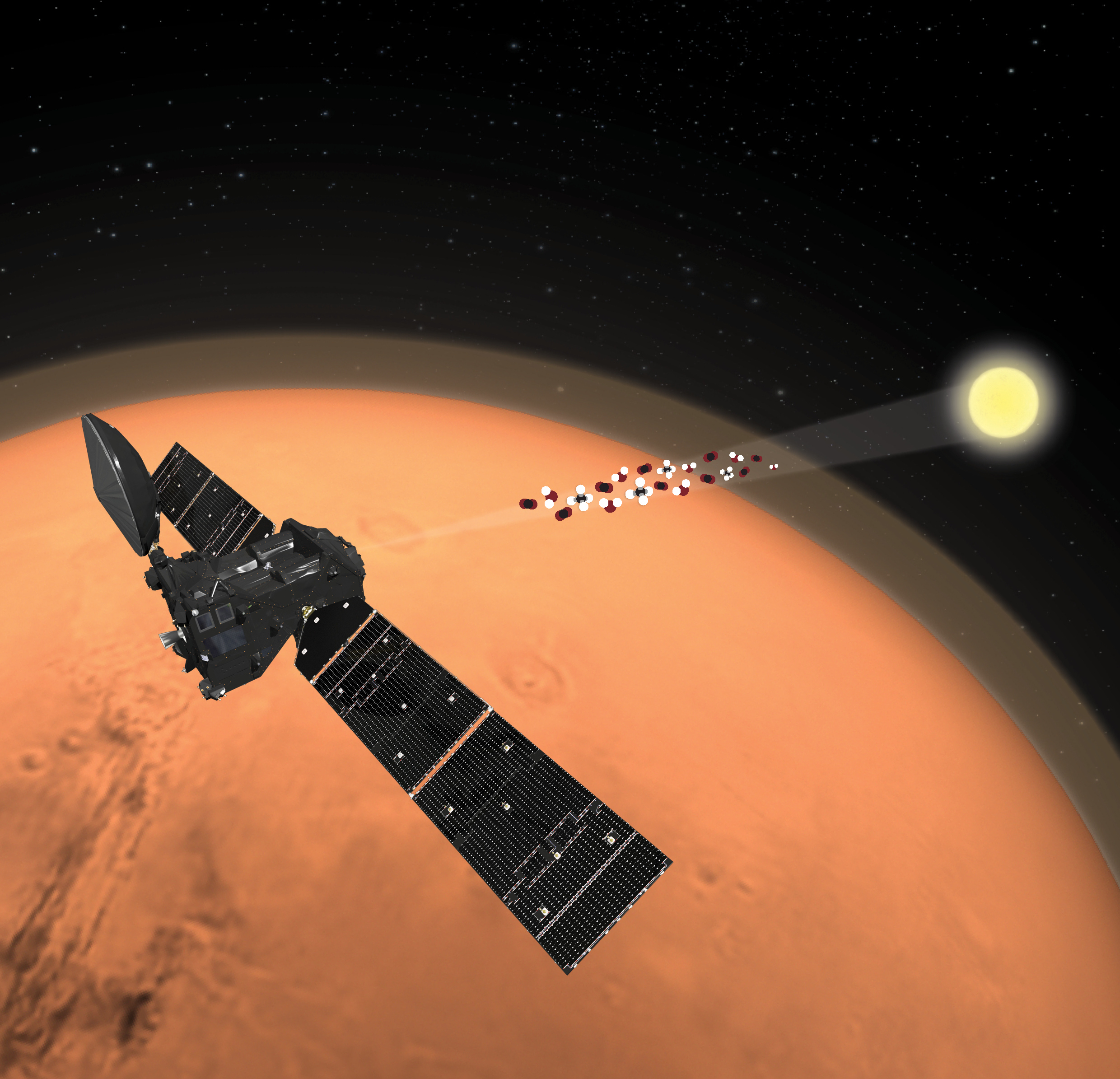

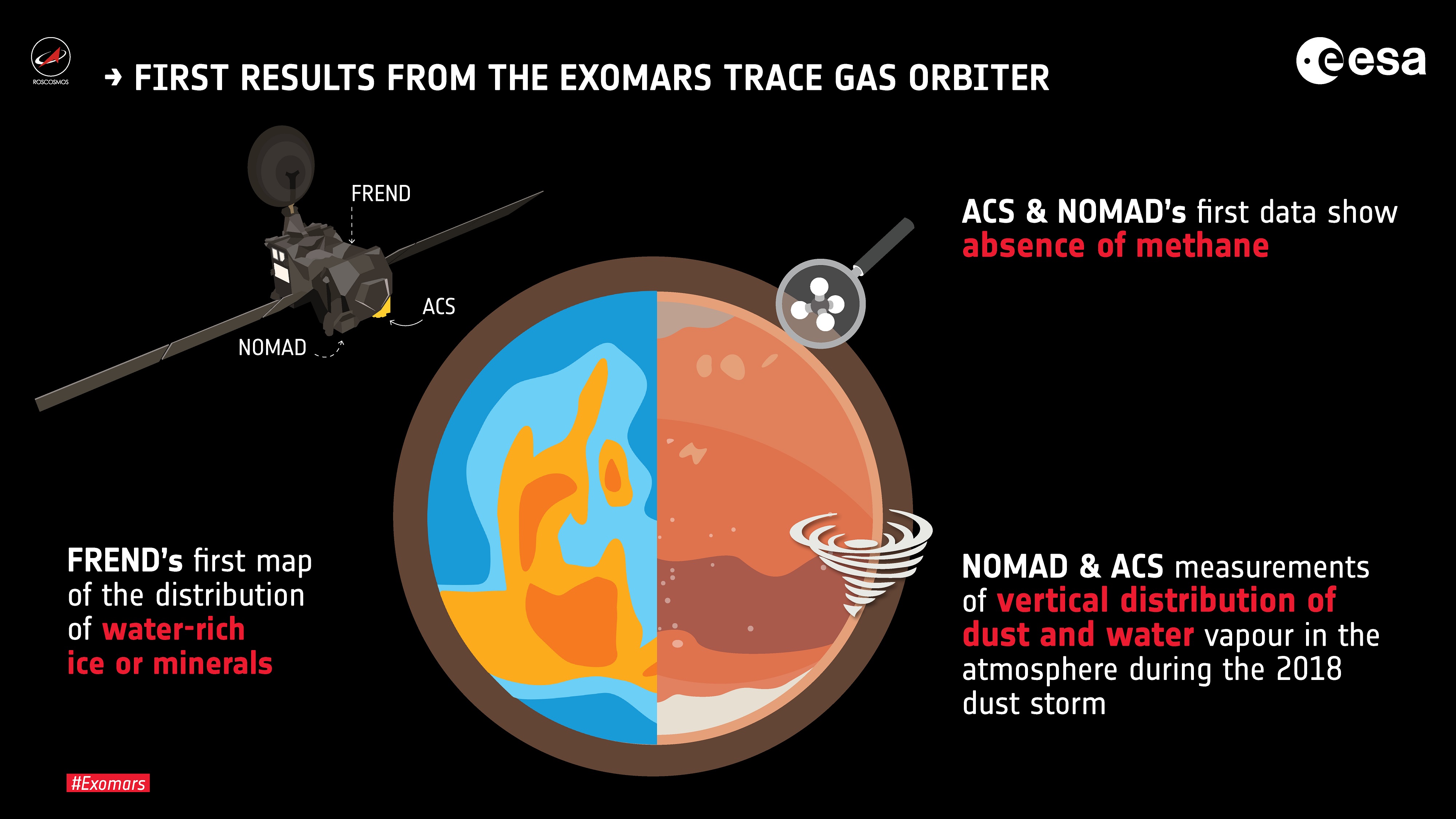

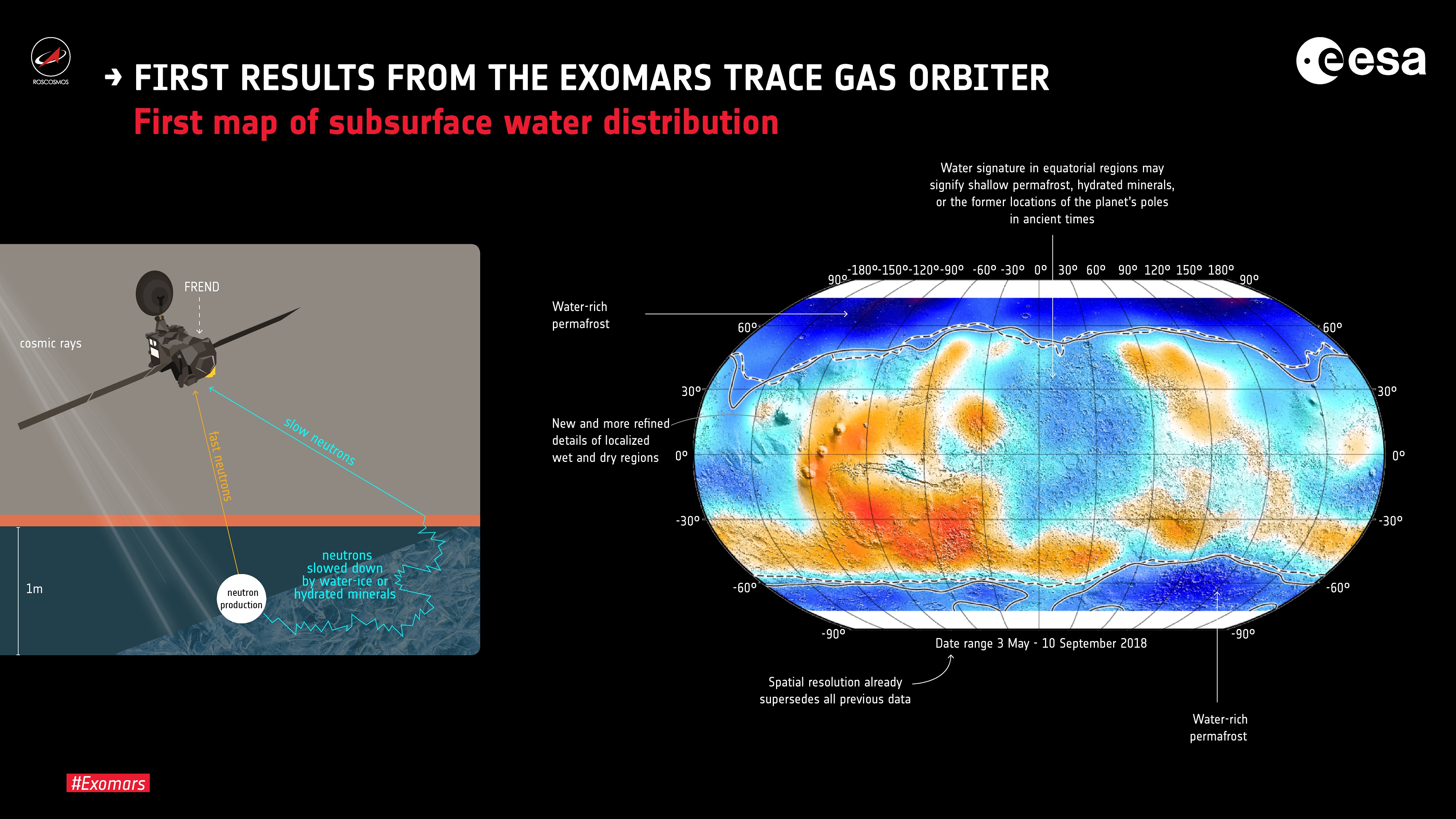

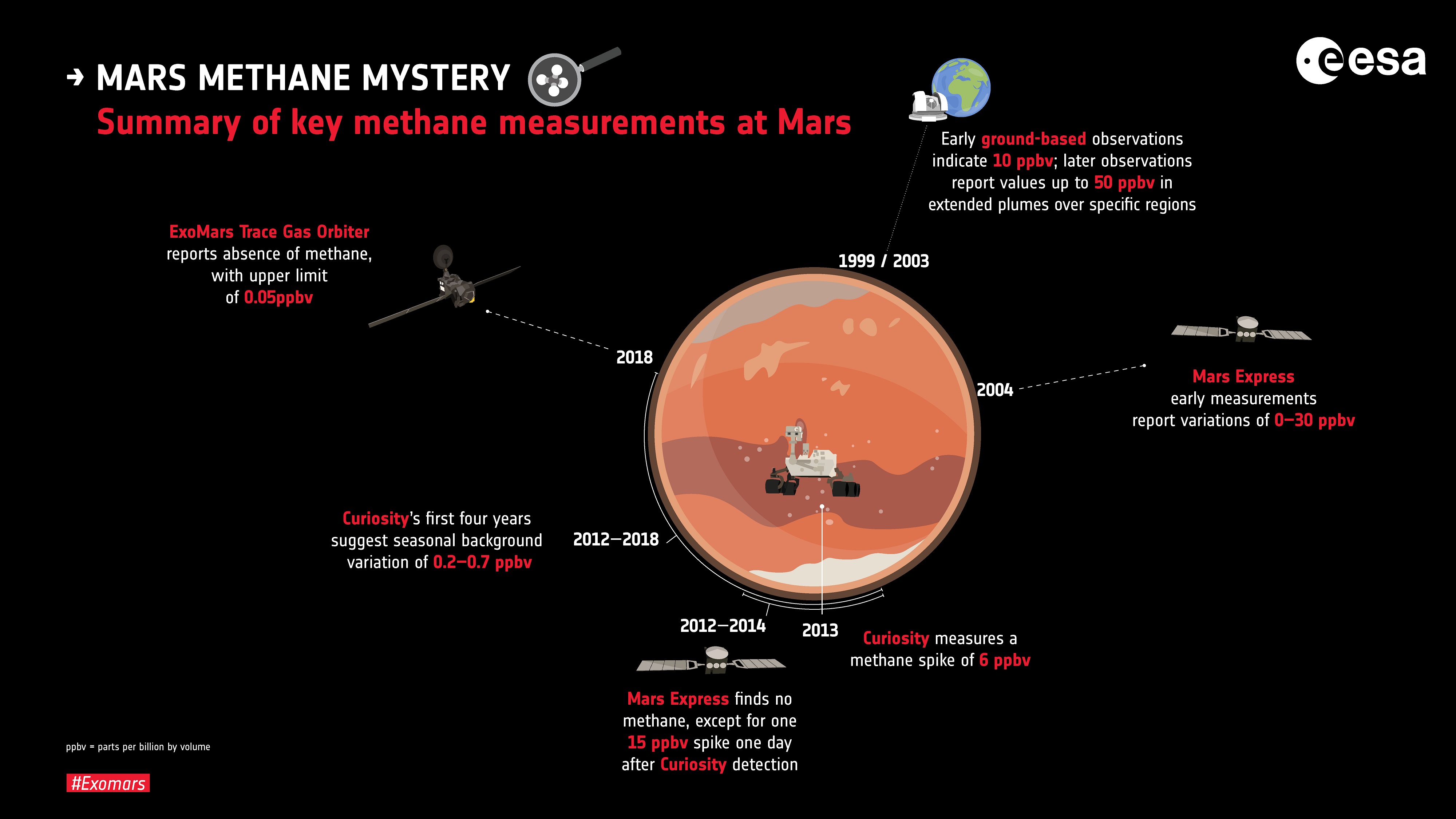

Now, the mystery deepens. Today (April 10), researchers reported the first results from the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), the spacecraft that's been circling the Red Planet sniffing for signs of life as part of the European-led ExoMars mission. To the surprise of scientists, TGO found barely any traces of methane in its early observations from April 2018 to August 2018.

Related: Missions to Mars: A Robot Red Planet Invasion History (Infographic)

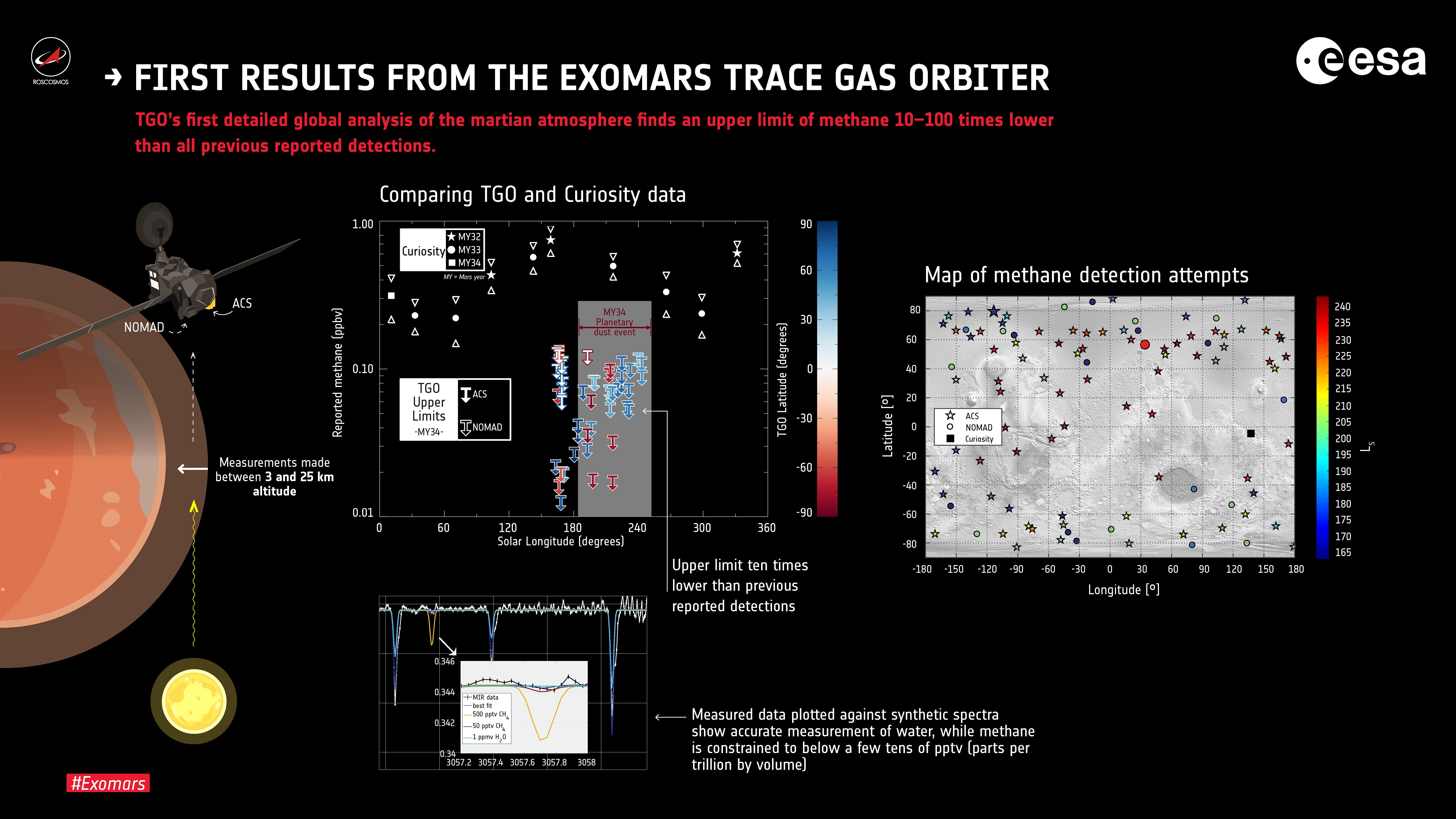

"TGO is the most sensitive instrument to measure methane on Mars," said Oleg Korablev, who is the principal investigator for the Atmospheric Chemistry Suite (ACS) instrument on the TGO and a scientist with the Russian Academy of Sciences' Space Research Institute. "We only can report upper limits which are very, very low."

The most precise upper limit Korablev and his colleagues found was just 0.012 parts per billion (ppb) — that's several orders of magnitude below the rate scientists would have expected based on the methane detected at the surface by NASA's Mars rover Curiosity. (Curiosity had detected background levels of methane 0.41 ppb during the same season in previous years.)

The discrepancy could mean methane is getting destroyed in the lower reaches of the Martian atmosphere. But scientists don't yet know how.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We have two completely independent instruments analyzed by two totally independent teams and they come to the same results," Håkan Svedhem, a TGO project scientist with the European Space Agency, told reporters during a news conference today. In addition to ACS, TGO also has another gas-measuring instrument known as NOMAD (Nadir and Occultation for Mars Discovery).

The researchers presented the results at the annual meeting of the European Geosciences Union in Vienna. Their findings were also published today in the journal Nature.

Marco Giuranna, a scientist with the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica in Rome who was not involved in the research, said it's not surprising for a spacecraft like TGO not to detect methane, as the presence of this gas on Mars is likely characterized by transient emission spikes, rather than by a global presence.

"Because methane is generally at very low concentrations in the atmosphere of Mars, methane spikes or pulses on Mars may only be detected occasionally — when rovers, landers or orbiters happen to be at the right place at the right time," Giuranna, who is the principal investigator of the Mars Express' Planetary Fourier Spectrometer instrument, told Space.com in an email. "Consistently, in our new Mars Express study, we did not detect any methane aside from one single definite detection." (Earlier this month, in the journal Nature Geoscience, Giuranna published those results about a 2013 methane plume observed by the Mars Express orbiter.)

Still, scientists had predicted that the concentrated plumes of methane should enter into global circulation around Mars, and that TGO should have detected some uniform distribution of the gas present in background levels.

The authors of the new study said that to reconcile the lack of methane detection by TGO and the positive methane detection by Curiosity at the surface, there must be a mechanism that destroys the gas in the lower atmosphere a thousand times faster than predicted by conventional chemistry.

"Methane on Mars seems to appear and disappear quickly, suggesting the presence of a destruction mechanism capable of efficiently removing this gas from the atmosphere," Giuranna said.

Researchers have proposed some explanations for where the methane on Mars could be going — that it could be sinking into the Martian rock and soil, or bonding chemically with eroded quartz grains, or being destroyed by reactive elements in shifting sand dunes — but these hypotheses are largely based on computer simulations and lab experiments on Earth.

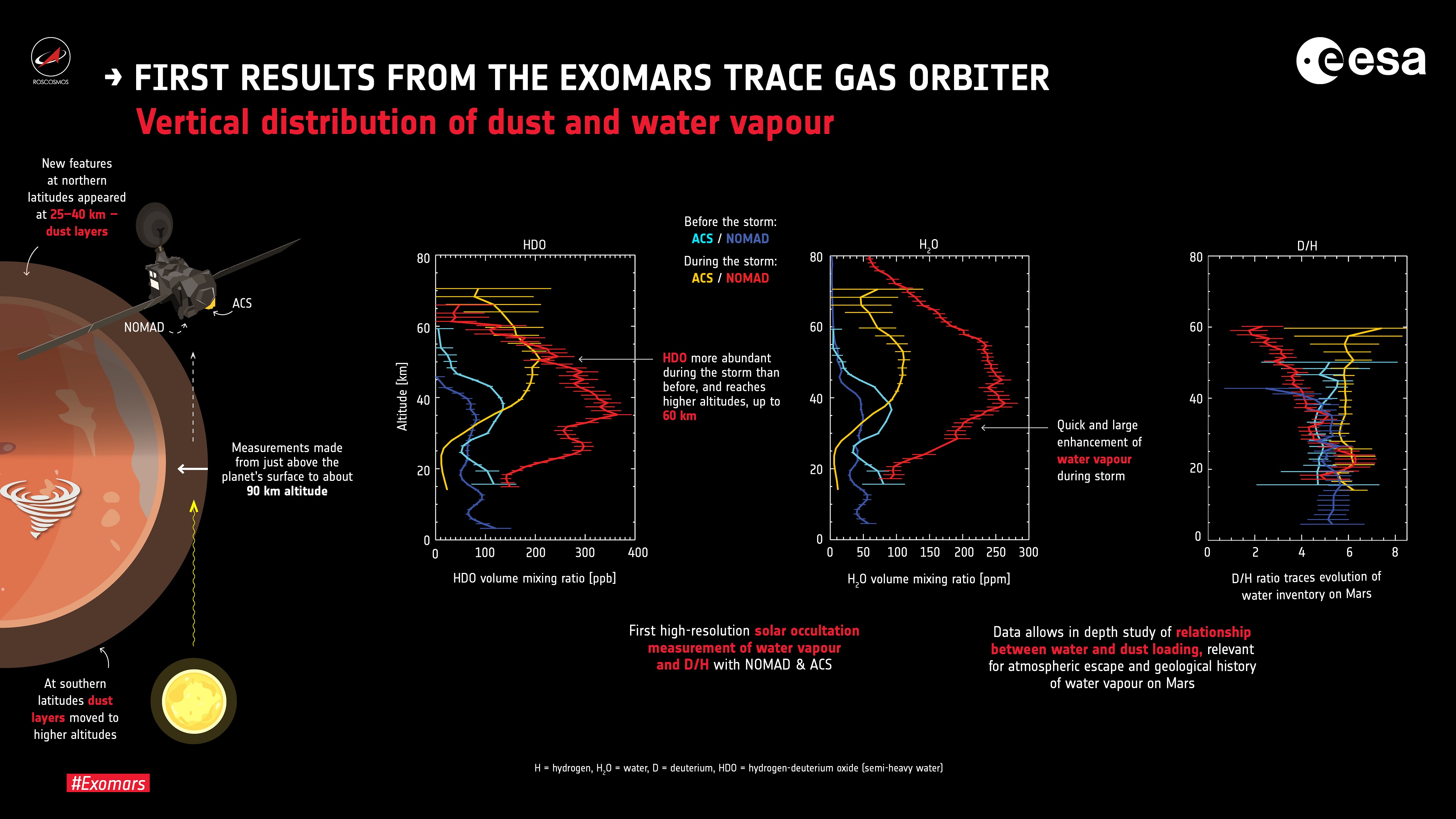

Giuranna speculated that the weather on Mars could have influenced TGO's observations, as one of the strongest, planetary-encircling dust storms ever seen on Mars began in June 2018.

"This might have an important impact on the results, as Martian dust storms represent a possible sink of atmospheric methane," Giuranna said. But the TGO researchers said they established stringent upper limits on methane before the storm, and Korablev told reporters: "We still do not see any methane after the dust storm."

Other scientists haven't given up hope that TGO will eventually detect greater concentrations of methane.

"We need to be more patient with TGO, because one thing we have learned is that the methane story is full of surprises, and there are surely more to come," Chris Webster, a senior scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, who also was not involved in the research, told Space.com in an email. "It would not surprise me if TGO detected methane sometime in the future."

And even though the presence of methane on Mars has been seen as a potential biosignature, Svedhem said TGO's findings were not necessarily a blow to the prospect of finding life on Mars.

"The speculations that were triggered by the first detections of methane stressed the connection between methane production on Earth and life on Earth," Svedhem told reporters. "But there are many other aspects of life that do not produce methane. So we definitely cannot say we have precluded that now."

- Mars' Atmosphere: Composition, Climate & Weather

- 7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars

- Ancient Mars Could Have Supported Life (Photos)

Follow Megan Gannon @meganigannon. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.