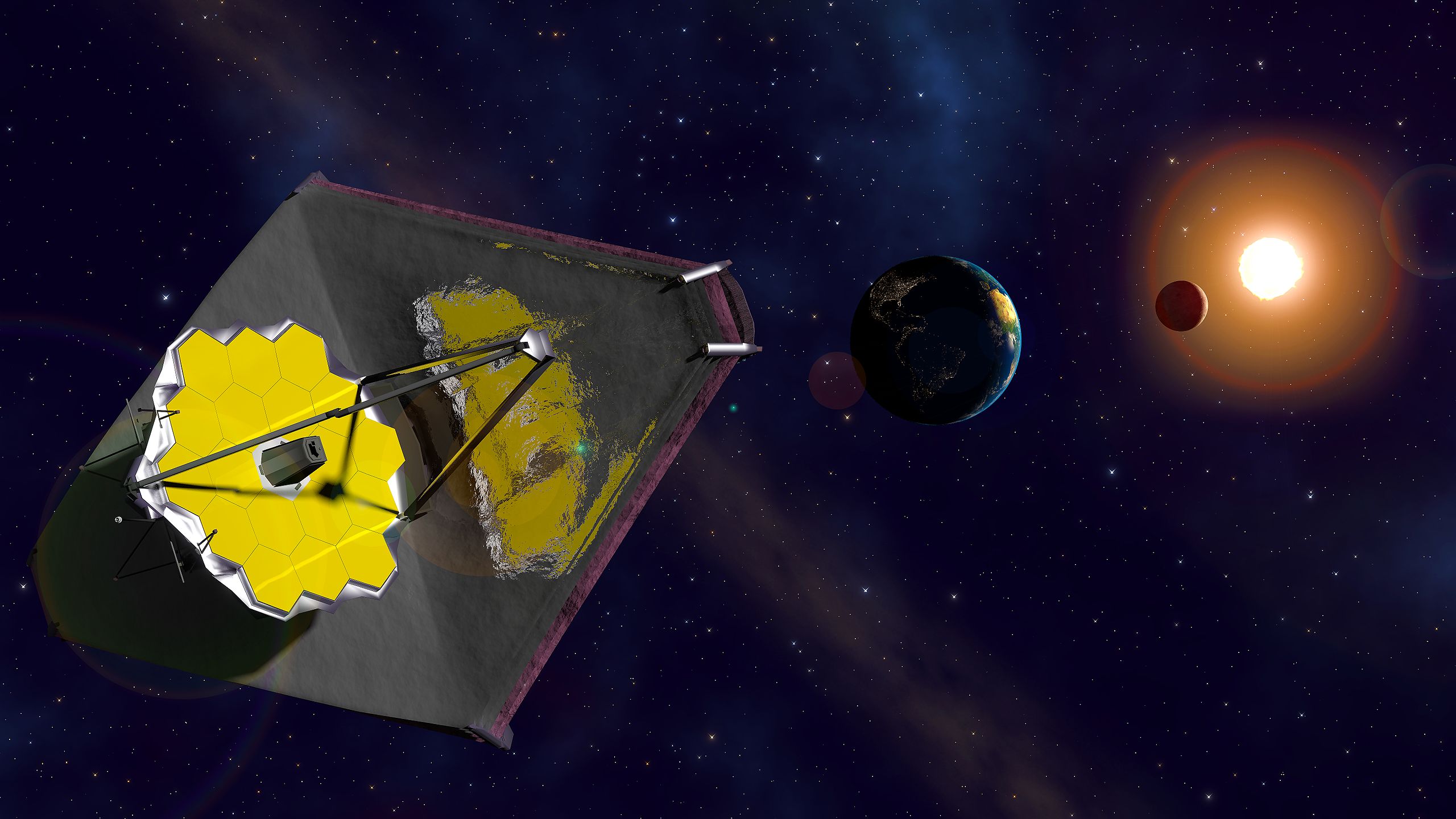

James Webb Space Telescope's supercold camera bounces back from glitch

MIRI will soon observe Saturn's polar regions.

The James Webb Space Telescope's supercold camera MIRI is back in full science mode after a technical problem on its grating wheel forced scientists to halt some observations.

The grating wheel on the Medium Resolution Spectrometer (MRS) of James Webb Space Telescope's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) allows astronomers to choose in which wavelengths of light to observe the surrounding universe. The wheel, which is used in only one of MIRI's four observing modes, started showing signs of friction in August, forcing the mission team to suspend observations in the affected mode.

After weeks of remote scrutinizing, engineers concluded that the problem was caused by "increased contact forces between the wheel central bearing assembly’s sub-components under certain conditions," the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, which is responsible for Webb's operations, said in a statement.

Related: Why the James Webb Space Telescope's amazing 'Pillars of Creation' photo has astronomers buzzing

The engineers have now given a green light for the affected spectroscopy mode to resume operations and are developing a set of recommendations on how to safely use the affected wheel, STScI said in the statement.

"An engineering test demonstrating new operational parameters for the grating wheel mechanism was successfully executed on November 2, 2022," STScI said in the statement. "MIRI is resuming MRS science observations, including taking advantage of a unique opportunity to observe Saturn’s polar regions. The JWST team will schedule additional MRS science observations, initially at a highly orchestrated cadence with additional trending measurements to monitor the new operational regime of the mechanism to prepare MIRI’s MRS mode for a return to full science scheduling."

When operating in the MRS mode, MIRI doesn't take images but light spectra, essentially light absorption fingerprints that reveal chemical compositions of the observed objects.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

MIRI's other three observing modes — imaging, coronagraphic imaging and low-resolution spectroscopy — have continued as normal during the MRS outage. The supercold camera has demonstrated its powers with a range of stunning images including a snap of the iconic Pillars of Creation, which revealed the intricate dusty formation in eerie detail.

MIRI, a specialist in detecting mid-infrared wavelengths, requires the coldest temperatures of all Webb's instruments to operate accurately. While the other three instruments — NIRCam, NIRSpec and FGS/NIRISS — rely on the telescope's location and its giant sunshield to maintain temperatures of minus 369.4 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 223 degrees Celsius), MIRI requires additional cryocoolers to get to an even colder temperature of minus 447 degrees F (minus 266 degrees C). That's only 12 degrees F (7 degrees C) above absolute zero, the temperature at which the motion of atoms stops. Since MIRI detects infrared light, which is essentially heat, any additional warmth would decrease the sensitivity of its measurements.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.