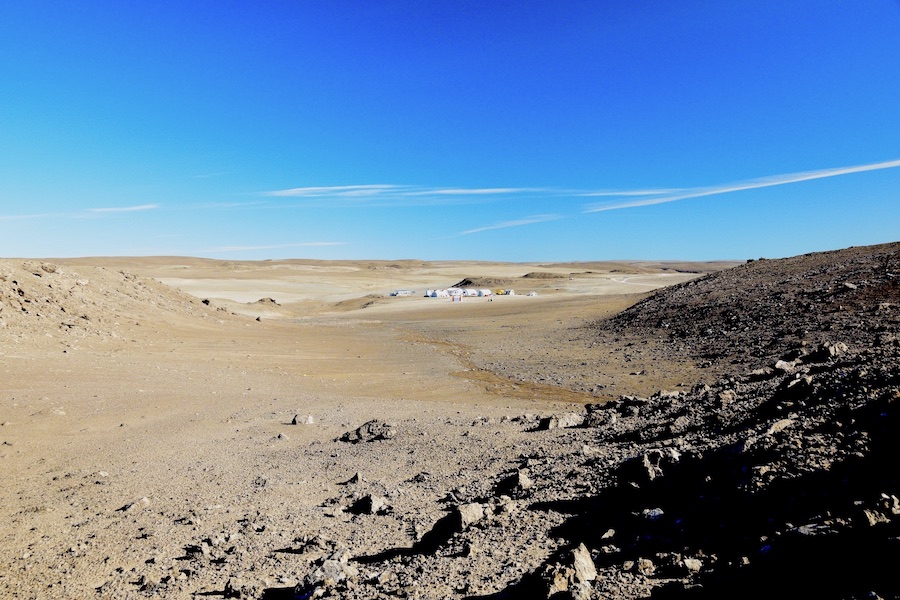

When flying to the Haughton-Mars Project (HMP) base, the primary impression is one of a vast wasteland below. The reddish expanse of dirt and rock looks featureless and bleak, but in fact holds many surprises for the uninitiated.

Paramount among these is the fact that this is a polar desert. While one expects an island within 15 degrees of the north pole to be icy and snow covered, there are only tiny patches of either here — they have melted away leaving small ponds and streams dotting the landscape. One of these ponds is our primary water source, where we drive every couple of days to replenish our supply.

Otherwise, the terrain is one of rolling, reddish hills; broad, rocky plains intersected by freeze-thaw features, some forming polygons (as seen near the Mars Phoenix lander); and the occasional rift, butte, or terrace. The view would not be completely out of place in parts of Utah or Arizona, except that there would be plants in those places — scrub brush, cactus, and the occasional stunted tree. There would also be wildlife — birds, rabbits, and coyote. Here there are none of those things; the only plant life evident are sparse patches of lichen and bits of slimy moss in the rare stream, and while there are birds and rabbits and polar bears on Devon, we've seen none; the only life we've encountered is lichen and the creek slime, likely algal mats, which we sampled for examination. It is easy to believe you've been transported to Percival Lowell's Mars from the 1890s, one in which you can breathe the air and endure the cold without a pressure suit.

Related: Mars missions: A brief history

That is precisely why Mars Institute planetary scientist Pascal Lee chose this as a site for his Haughton-Mars Project base in 1997, beginning construction in 2000. While the 22 years of continued existence in the harsh environment have taken their toll — the tent buildings are worn and the lumber is splintering in places — it is in remarkably good shape given the modest budget and minimal manpower available for primary maintenance.

The fact that the HMP exists at all is an act of sheer willpower on Pascal's part. He initially came up with the idea of siting a Mars analog base here as his first project out of graduate school. The site was selected for its general resemblance to Mars, but in particular due to its proximity to the Haughton Impact Crater, a feature formed by a massive asteroid or comet strike some 23 million years ago.

So besides being arid, barren of noteworthy plant life, rocky, sandy, and of a ruddy hue, the region has one of Earth's more pristine impact craters — a landform of which Mars has no shortage. And beyond the crater, there are also amazingly Mars-like gullies, valleys, and canyons. It was the perfect place to put a Mars analog base.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Rod Pyle is a space historian and author who has created and offered executive leadership and innovation training at NASA's Johnson Space Center. Rod has received endorsements and recognition from the outgoing Deputy Director of NASA, Johnson Space Center's Chief Knowledge Officer for his work.

You've probably seen other such facilities—small groups of people locked in a fabric dome or fiberglass cylinder who don simulated space suits each time they wish to leave the habitat, simulate a depressurization cycle in a simulated airlock, and then amble across a rocky plain in Utah, Hawaii, or even up here, communicating with "Earth" via a simulated radio delay. While those experiential simulations have some value, that is not what Pascal created the HMP to do. Rather, this facility was created in association with NASA and a number of corporate sponsors to study approaches to Mars exploration.

Collins Aerospace has sent up space suit engineering models for testing here. NASA's Ames Research Center has tested robotic drills, rovers, and helicopters for Mars here, and NASA's Langley Research Center has flown a winged vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) Mars prototype. NASA's Johnson Space Center has conducted Moon and Mars pressurized rover roadtrip and spacewalk studies using the HMP's specially modified Humvees with their exterior suitports, airocks that attach directly to spacesuits and may one day allow astronauts to go on extra-vehicular activities nimbly and quickly.

But siting a research center on an Arctic island is not a trivial task. It can cost as much to transport the materials here as it does to buy them, and delivering a crew to construct the facility was itself a large undertaking. Pascal's primary partner in the venture is the aforementioned John Schutt, a long-time veteran of other Arctic and Antarctic ventures.

Pascal's life has been eclectic. Born in Hong Kong in 1964, he went to France to attend boarding school near Paris when he was just eight years old. Upon graduating from the Sorbonne with an undergraduate degree in physics and a graduate degree in engineering geology and geophysics, he performed his French National Service in Antarctica at the Dumont d'Urville base, staying for over 400 days and performing geophysical research.

Prior to leaving for his Antarctic posting, Lee applied to Cornell University for a graduate program in astronomy and space sciences — Carl Sagan was teaching there at the time, as was Joe Veverka, who was deeply involved with planetary imaging on almost every NASA mission across the solar system. Pascal worked extensively with Veverka and was Sagan's last teaching assistant. His acceptance to Cornell was Telexed to him while in Antarctica.

— A month on 'Mars': Preparing to visit the Red Planet ... on Earth

— A month on 'Mars': Traveling to the Red Planet

— A month on 'Mars': First journeys in our Arctic home

— A month on 'Mars': Get to know the Haughton-Mars Project

— A month on 'Mars': Trekking across the Arctic

— A month on 'Mars': Journey to the 'Planet of the Apes Valley'

— A month on 'Mars': Flags and footprints of the moon and Arctic

— A month on 'Mars': The Arctic comes alive

— A month on 'Mars': Fogbound on Devon Island

— A month on 'Mars': Trekking through Ingenuity Valley

— A month on 'Mars': Living on the EDGES

Pascal's fascination with the Haughton region began while he was still in graduate school, looking for the best possible Mars analog on Earth, which he thought would have to be in our planet's polar regions. After landing a posdoctoral position at NASA Ames and an initial visit to Haughton Crater in 1997, he decided to build a base nearby, affiliated with NASA and intended for serious scientific work. In its most recent form, the base had nine structures and hosted scientific work every summer (and during the occasional winter), but COVID caused a break in occupation due to regional travel restrictions, and the harsh elements have damaged two buildings.

But Lee is undaunted, and with the help of Schutt and others intends to continue improving HMP. It's rare to meet someone so driven who is not motivated by financial gain, but by a true thirst for exploration and discovery. "This is truly Mars on Earth," he says, surveying the starkly beautiful hills and valleys surrounding us. "There's no better place on Earth to test systems and strategies for exploring Mars, and that's what I hope we'll continue doing here with NASA, the SETI Institute, and all our other partners." In fact, Collins Aerospace, the company selected to fabricate new EVA suit systems for NASA's Artemis program, will soon be sending up new spacesuits for testing here.

And with that, he smiles like a person who has found and engaged his deepest purpose in life and turns away from the sublime to attend to the mundane — helping to prepare dinner for our group of researchers and others visiting "Mars" for the next three weeks.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rod Pyle is an author, journalist, television producer and editor in chief of Ad Astra magazine for the National Space Society. He has written 18 books on space history, exploration and development, including "Space 2.0," "First on the Moon" and "Innovation the NASA Way." He has written for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech, WIRED, Popular Science, Space.com, Live Science, the World Economic Forum and the Library of Congress. Rod co-authored the "Apollo Leadership Experience" for NASA's Johnson Space Center and has produced, directed and written for The History Channel, Discovery Networks and Disney.