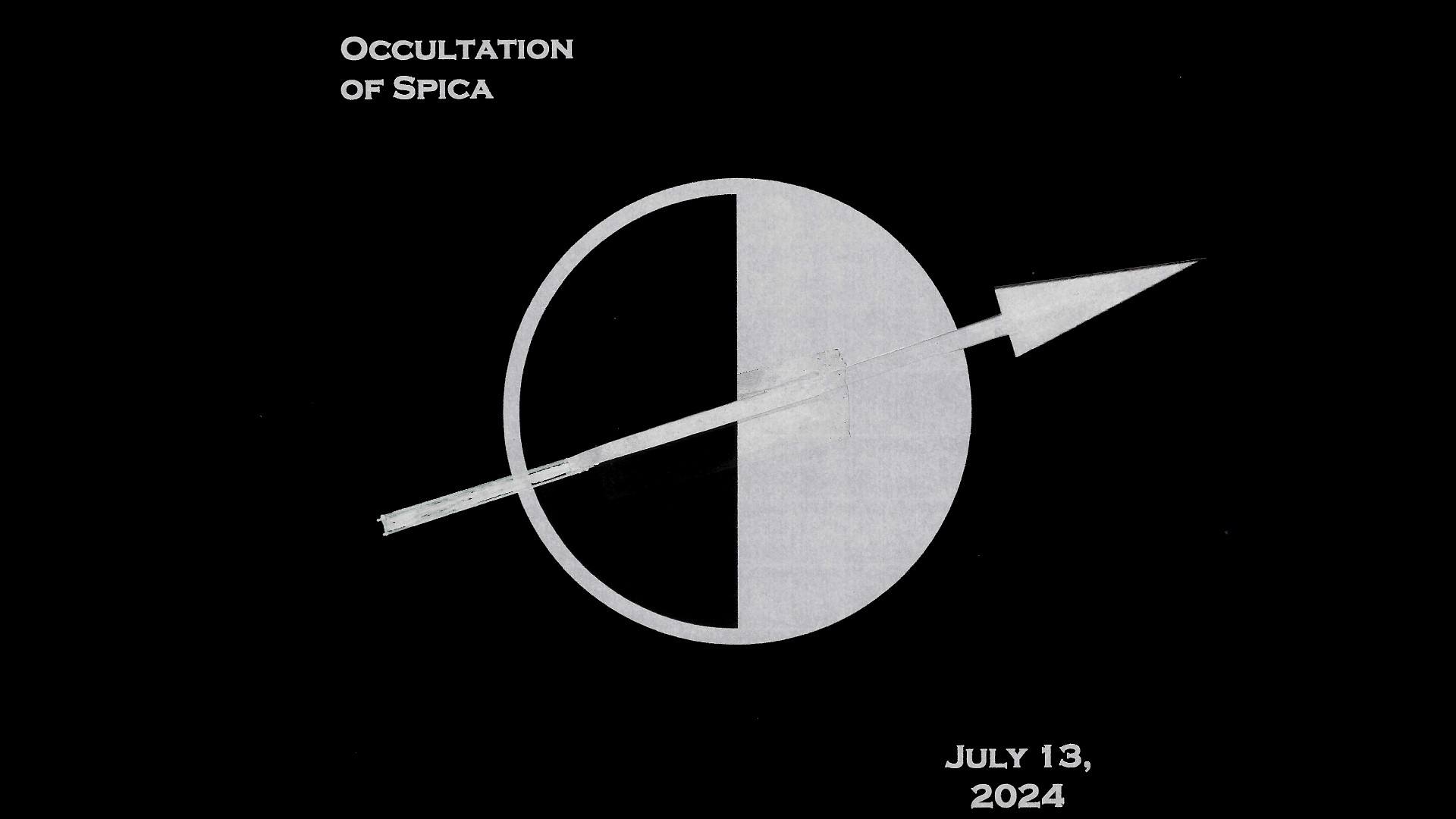

One of the most interesting events in visual astronomy, and certainly the fastest, occurs when the moon occults a star. The moon's edge creeps up to it, seems almost to press against it for a number of seconds, and then suddenly the star is gone! It reappears just as abruptly on the moon's other side up to an hour or more later.

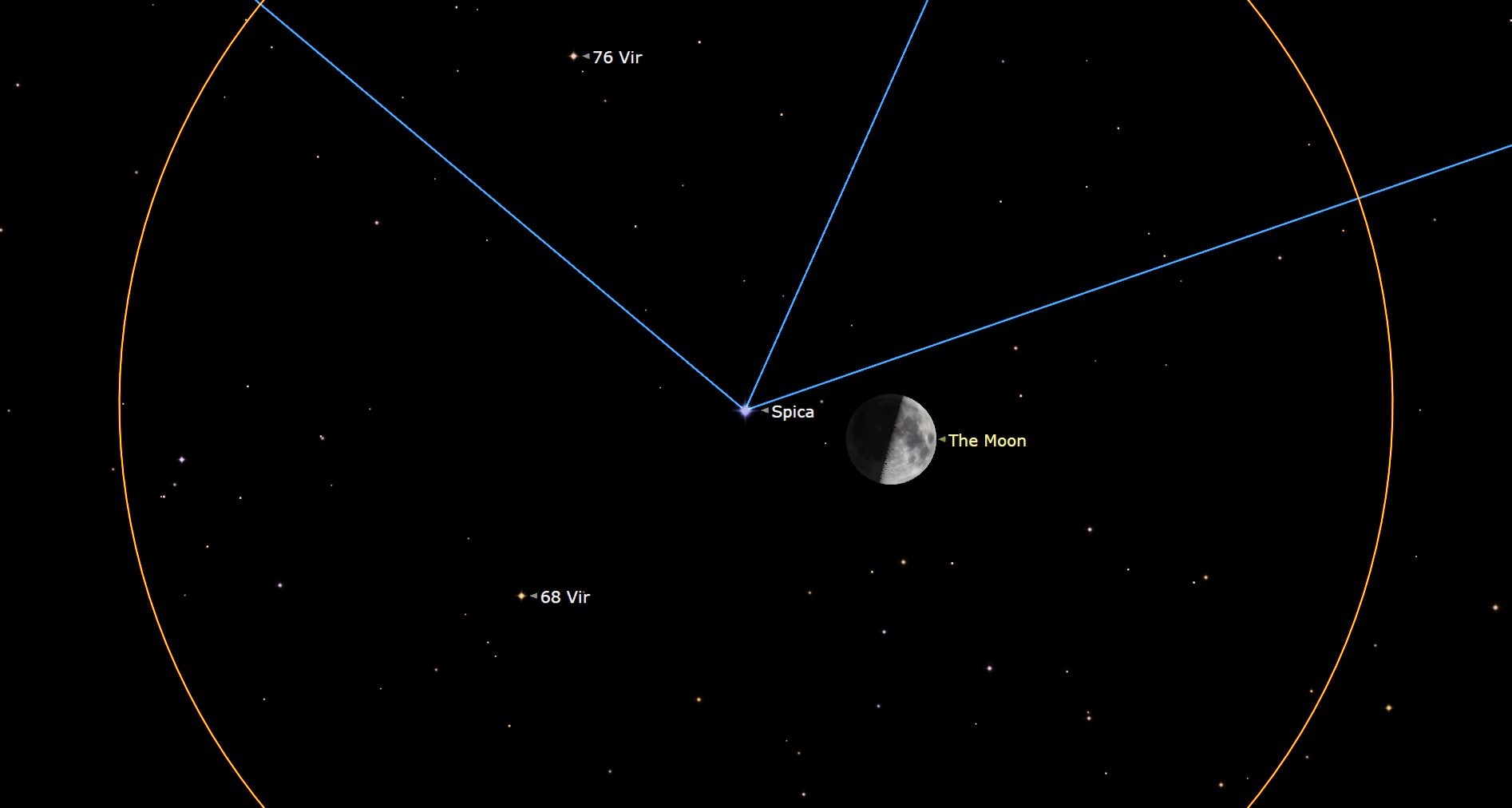

On Saturday (July 13) anyone with a telescope and a clear sky should be concentrating on that evening's moon, just past the first quarter (52% illuminated). That will be when the moon will pass in front of the 1st-magnitude star Spica as seen from North America.

Because the moon is waxing, its dark side faces forward as it advances eastward against the starry background. Spica will thus disappear on the dimly Earth-lit dark limb of the moon, a dramatic sight. In a dark sky, Spica will seem to suddenly "click off," a stunning demonstration of the moon's orbital motion and the star's tiny angular size. Binoculars or maybe even just your eyes will be all you'll need.

Spica's reappearance on the other hand, will happen on the moon's bright limb, and even such a brilliant blue diamond will be partly overwhelmed by the glaring lunar surface for some seconds after it reappears. How well you see the moment of reappearance will depend on the size and quality of your telescope and the steadiness of the local atmospheric seeing.

If you're looking for binoculars or a telescope to see lunar occultations like these up close, or anything else the night sky, be sure check out our guides for the best binoculars and best telescopes.

And if you're interested in taking photos of evens like these, don't miss our guide on how to photograph the moon. We also have recommendations for the best cameras for astrophotography and the best lenses for astrophotography.

What to expect

Want to observe lunar occultations up close? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

Along and near to the Atlantic Seaboard, Spica's disappearance will be visible, albeit rather low — for the mid-Atlantic and Northeast states, generally 10 degrees or less above the west-southwest horizon. Keep in mind that your clenched fist, held out at arm's length measures about 10 degrees in width. So, for many locales, Spica will disappear behind the moon less than "one fist" above the horizon. Over the Southeast states, Spica and the moon will appear several degrees higher in altitude.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For places to the right of a line running roughly from Toronto, Ontario south to Miami, Florida, Spica's reappearance does not happen until after the moon has set.

Probably the best region to watch this event is from the central part of the country, where the entire occultation, from start-to-finish, occurs generally in a dark sky.

Farther west, it will be closer to the time of sunset. To the east of the Rockies, the disappearance will occur during early evening twilight, while the reappearance happens in a dark sky.

West of the Rockies, Spica will disappear before sunset and will reappear during bright twilight. Over the Pacific Northwest, the entire occultation will unfortunately take place before sunset in a daytime sky; when darkness falls, Spica will be visible just to the right of the moon.

When to look

In the table below, we provide local viewing times for 15 selected cities. "Daytime" indicates the event occurs prior to sunset. Times accompanied by an asterisk (*) indicates that event occurs during twilight. "Below Horizon" indicates that the moon and Spica have set and hence are not visible. For Atlanta, Georgia, Spica reappears after midnight on the calendar date, July 14.

For a more concise listing of times which includes over 700 locations across Canada, the USA, Mexico and Central America, as well as a map which shows the zone of visibility visit the International Occultation Timing Association (IOTA) page for this particular occultation.

| Location | Disappears | Reappears |

|---|---|---|

| San Francisco | Daytime | 8:44 p.m. |

| Denver | 8:49 p.m.* | 10:10 p.m. |

| Winnipeg | 9:44 p.m.* | 10:58 p.m.* |

| Helena | Daytime | 9:49 p.m.* |

| Kansas City | 10:05 p.m. | 11:22 p.m. |

| Chicago | 10:10 p.m. | 11:22 p.m. |

| Austin | 10:18 p.m. | 11:36 p.m. |

| New Orleans | 10:29 p.m. | 11:43 p.m. |

| Toronto | 11:15 p.m. | Below Horizon |

| Montreal | 11:16 p.m. | Below Horizon |

| Boston | 11:24 p.m. | Below Horizon |

| New York | 11:25 p.m. | Below Horizon |

| Washington | 11:26 p.m. | Below Horizon |

| Atlanta | 11:29 p.m. | 12:40 a.m. (July 14) |

| Miami | 11:48 p.m. | Below Horizon |

Where to look

The accompanying diagram shows Spica's general path behind the moon as seen across much of the United States.

Spica facts

Spica is the brightest star in the constellation Virgo, the Virgin. Virgo is the only female figure among the zodiacal signs and has been thought to represent a great array of deities since the beginning of recorded history. Virgo is usually shown either holding an ear of wheat or carrying the scales of Libra, the adjoining constellation.

Spica is almost exactly first magnitude, although it shows some slight variations; it's actually two stars whose components orbit each other every four days. They are so close together that that they cannot be resolved as two stars through a telescope and their respective shapes are mutually distorted so as to resemble ellipsoids.

Spica's name is derived from the Latin spīca virginis "the virgin's ear of [wheat] grain". It was also anglicized as "Virgin's Spike." The primary star is more than seven times larger, more than 11 times as massive and is more than 20,000 times more luminous than our sun.

Our best current estimates place Spica at a distance of 250 light years away (give or take 10 years). That having been said, perhaps in the year 2026, we might make reference to Spica as "America's Star," since during that summer the light that we see from that star likely will have started on its journey toward Earth in 1776, the year when America proclaimed its independence.

So, it would seem fitting to reference Spica often in 2026, during that year's sestercentennial (250th anniversary) of the United States.

Next time

Should clouds or unsettled weather prevent you from getting a view of Saturday's stellar eclipse, you'll get another opportunity early on Wednesday morning, Nov. 27, when another occultation of Spica takes place for North America. In the East, the occultation will take place near sunrise, while in the West the moon will interact with Spica in a dark sky, but rather low to the east-southeast horizon.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.