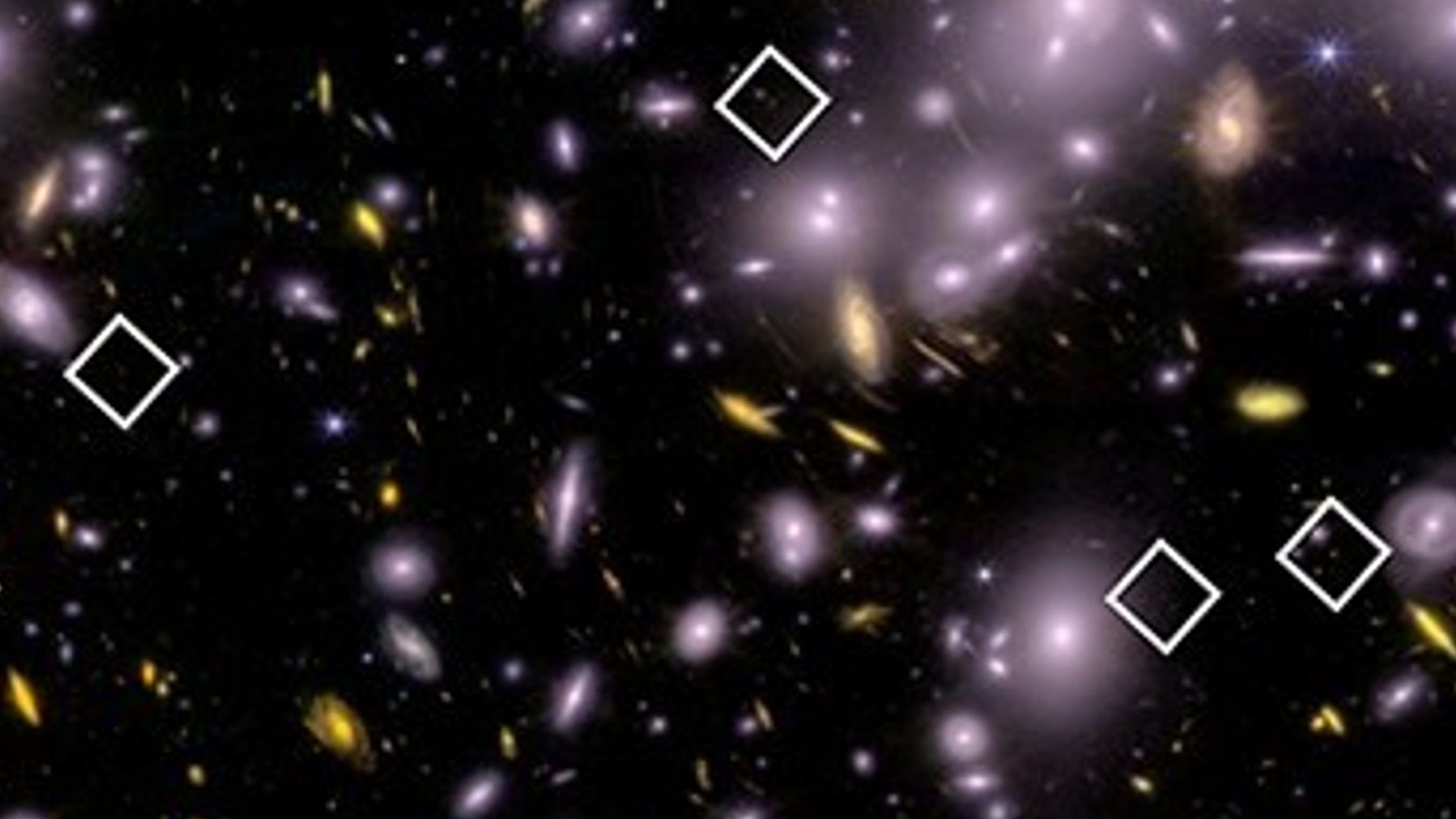

Buried oceans like the one thought to slosh beneath the icy surface of the dwarf planet Pluto may be incredibly common across the cosmos.

A gassy insulating layer probably keeps Pluto's liquid-water ocean from freezing solid, a new study reports. And something similar could be happening under the surfaces of frigid worlds in other solar systems as well, study team members said.

"This could mean there are more oceans in the universe than previously thought, making the existence of extraterrestrial life more plausible," lead author Shunichi Kamata, of Hokkaido University in Japan, said in a statement.

Related: Photos of Pluto and Its Moons

Pluto's "Heart" Hints at Buried Ocean

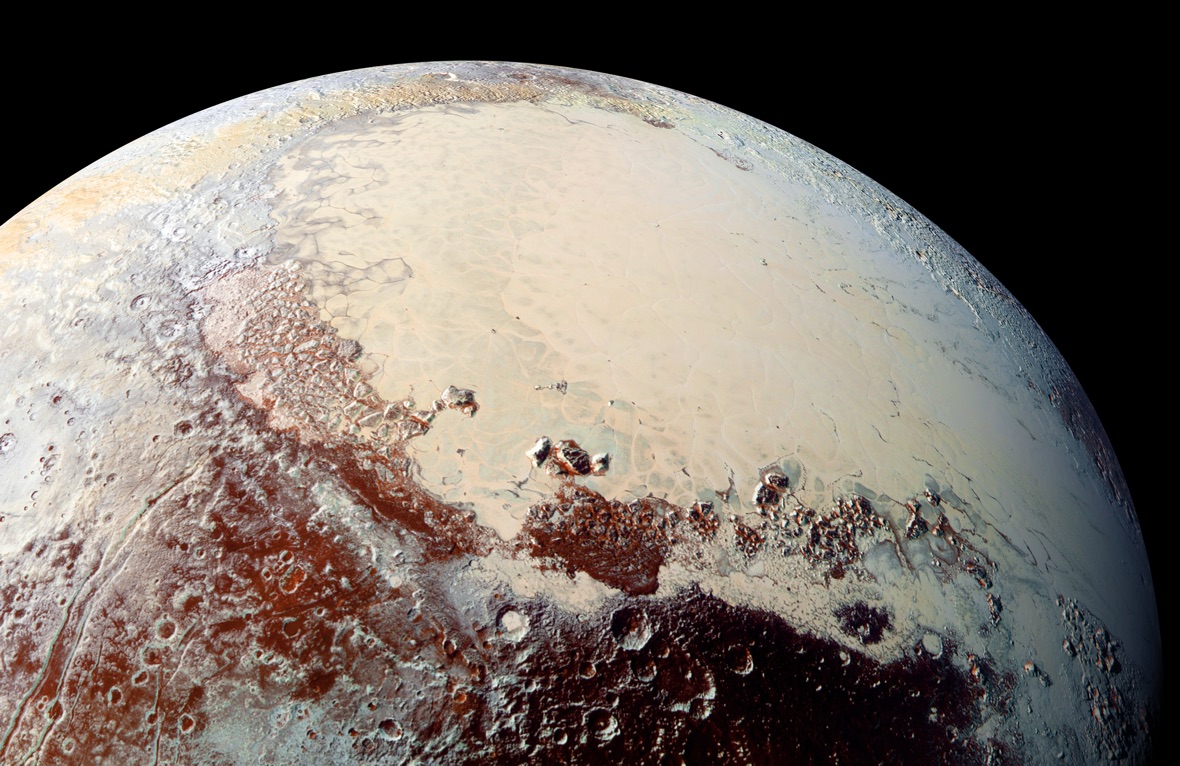

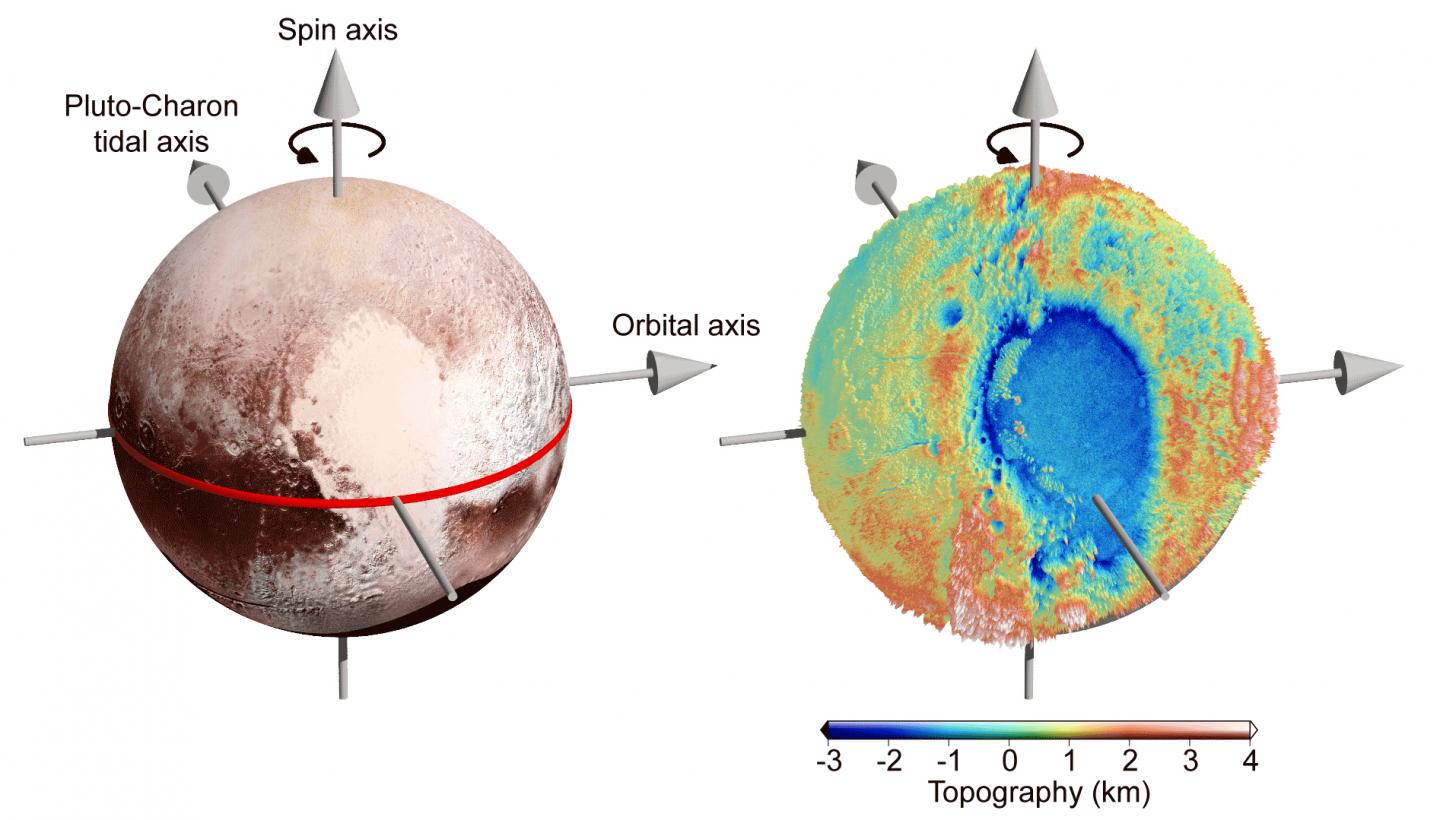

The case for a subsurface ocean on Pluto is bolstered by the location of Sputnik Planitia, a 600-mile-wide (1,000 kilometers) plain of nitrogen ice that forms the left lobe of the dwarf planet's famous "heart."

Observations by NASA's New Horizons probe showed that Sputnik Planitia is aligned with Pluto's tidal axis — the line along which the gravitational pull from the dwarf planet's biggest moon, Charon, is most powerful. Scientists think that Pluto rolled into this orientation because of extra mass concentrated at and near the surface in the Sputnik Planitia region.

That extra mass likely comes from the nitrogen ice that's built up on the plain, as well as water from the buried ocean, which was freed to rise from deep underground after the comet impact that formed Sputnik Planitia shattered the crust in that locale, previous research suggests.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

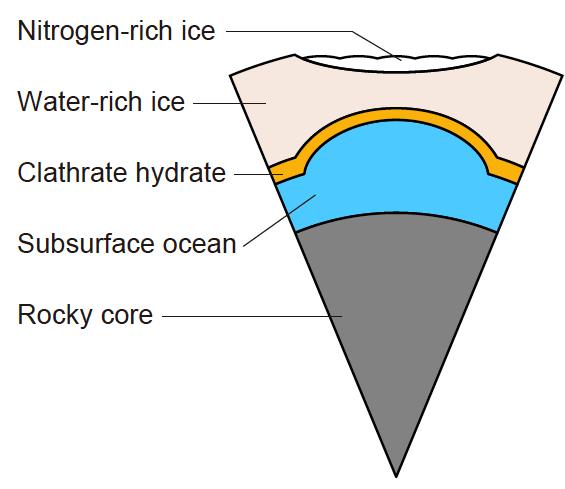

But how could a buried ocean stay unfrozen on Pluto over the 4.6-billion-year history of the solar system? After all, the dwarf planet doesn't circle a gas giant, so its innards aren't roiled and heated by tidal forces nearly as dramatically as are the insides of Jupiter's moon Europa and the Saturn satellite Enceladus, both of which also harbor subsurface oceans.

The new study offers a possible explanation. Kamata and his colleagues hypothesized that an insulating layer of "gas hydrates" — ice-like solids composed of gases trapped within "cages" of molecular water — beneath Pluto's ice shell might be responsible, then performed computer simulations to test the idea.

In simulations run without the gas hydrates, Pluto's ocean froze solid hundreds of millions of years ago. But with the insulating layer, the ocean persists to this day, the researchers found. The gas hydrates also act as an insulator in the other direction, helping to keep Pluto's surface cold enough to support observed variations in ice-shell thickness, the researchers said.

It's unclear what the gas inside the water cages might be (if such a layer does indeed exist). But the study team thinks methane is a good candidate, partly because Pluto's wispy atmosphere is notably lacking the stuff.

The new study was published online today (May 20) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

- Pluto Flyby Anniversary: The Most Amazing Photos from NASA's New Horizons

- Pluto Quiz: How Well Do You Know the Dwarf Planet?

- 6 Most Likely Places for Alien Life in the Solar System

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.