Rogue rocket poised to hit moon is Chinese, not a SpaceX Falcon 9, student observations confirm

The big event takes place March 4.

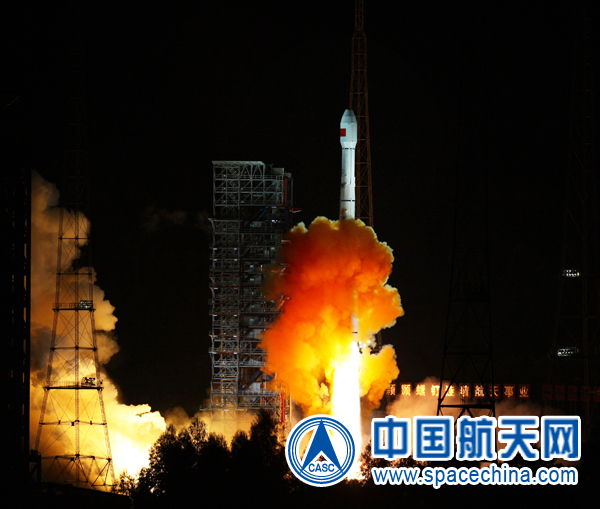

A group of students has confirmed that a rocket stage poised to hit the moon next month is from a Chinese Long March launcher, not a SpaceX Falcon 9 as originally thought.

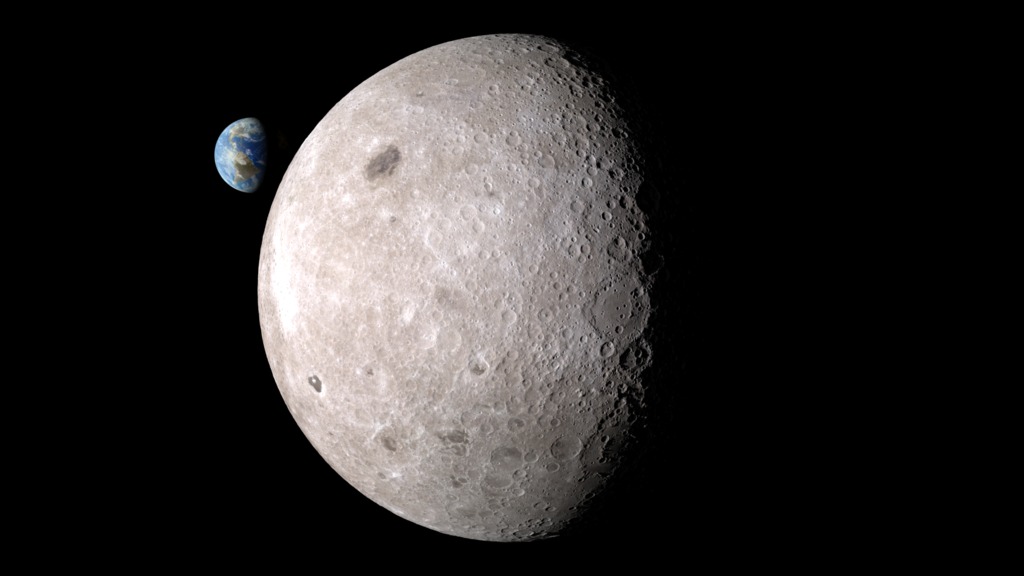

The rocket body, from the Chang'e 5-T1 mission, is set to slam into the moon's far side on March 4, more than seven years after its October 2014 launch. The object was originally misidentified as the upper stage of the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket that launched the Deep Space Climate Observatory satellite in February 2015.

"We took a spectrum, which can reveal the material makeup of an object, and compared it with Chinese and SpaceX rockets of similar types ... it matches the Chinese rocket," University of Arizona supervisor and associate professor Vishnu Reddy, who also co-leads the school's Space Domain Awareness lab, said in a statement Tuesday (Feb. 15).

"This is the best match, and we have the best possible evidence at this point," Reddy added of the new observations, which match independent work made public a few days ago. Students on the Arizona team include Grace Halferty, Adam Battle and Tanner Campbell.

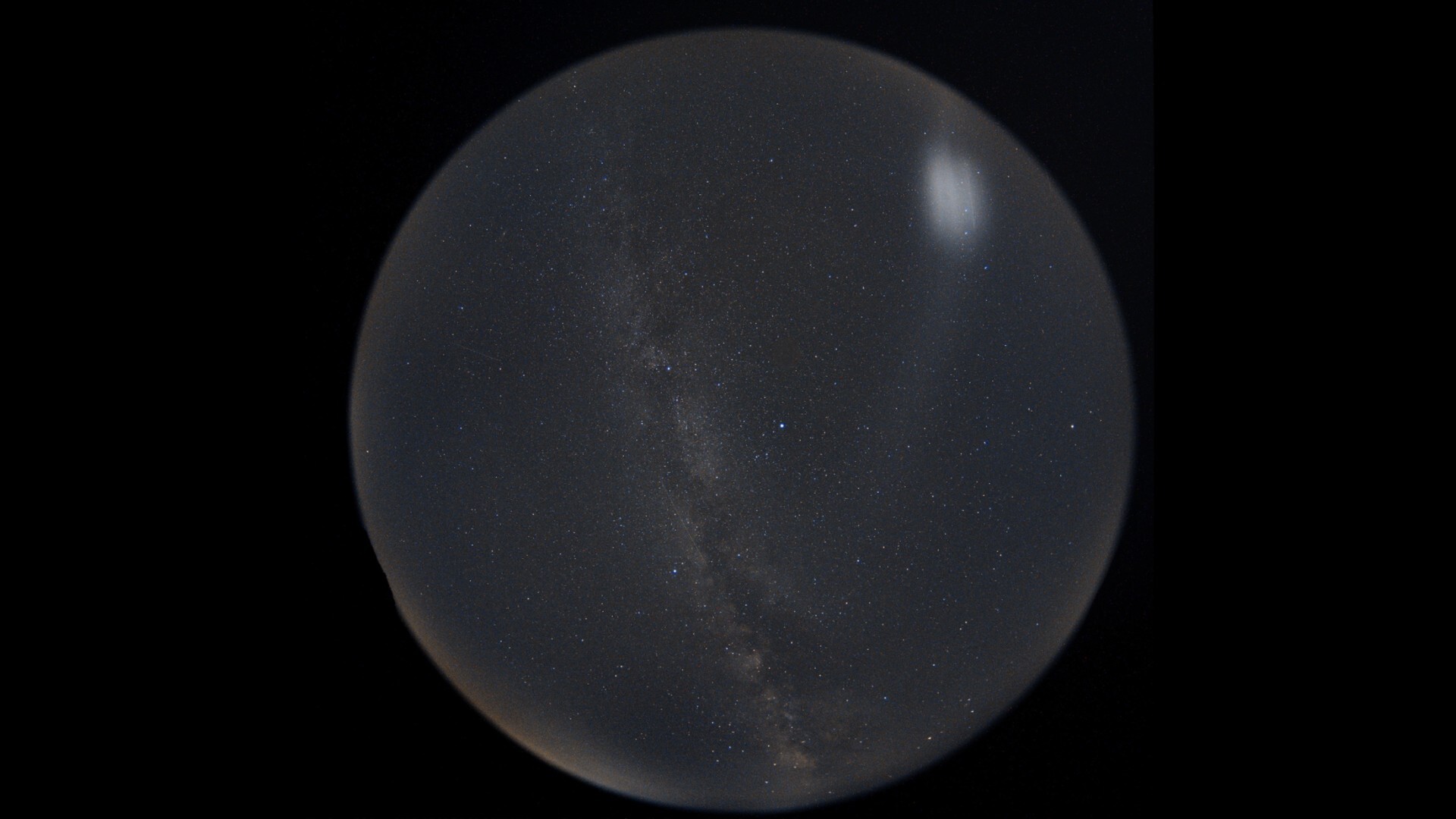

Video: Rocket stage to slam into moon, seen by Virtual Telescope Project

Related: The greatest moon crashes of all time

If you spot the rocket stage in a telescope before it hits the moon, let us know! Send images and comments in to spacephotos@space.com.

The original, mistaken identification of the rocket body as a Falcon 9 upper stage came from Bill Gray, who manages the Project Pluto software used to track near-Earth objects.

He published an explanation Saturday (Feb. 12) about his rationale for originally identifying the rocket as part of a Falcon 9.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I and others came to accept the identification with the second stage [of Falcon 9] as correct," Gray wrote. "The object had about the brightness we would expect and had showed up at the expected time and moving in a reasonable orbit."

Gray added, however, that the original evidence was not conclusive. And on Saturday, he said, he received a note from Jon Giorgini, an engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, pointing out that DSCOVR's postlaunch trajectory didn't take it all that close to the moon. After conducting further research, Gray wrote, he became convinced that the moon-bound rocket stage is actually from China's Chang'e 5-T1 mission, a precursor to the more famous Chang'e 5 mission that brought a sample of the moon back to Earth in 2020.

The University of Arizona students confirmed this newer work of Gray and others using the RAPTORS system, a telescope on top of the school's Kuiper Space Sciences building.

The group, however, performed their observations on the nights of Jan. 21 and Feb. 7, before Gray published his correction notice. "They estimate that it will hit somewhere in or near the Hertzsprung crater on the moon's far side," the university noted of the students' work.

"We don't often get a chance to track something we know is going to hit the moon ahead of time," Campbell added in the statement. Campbell is an aerospace and mechanical engineering graduate student who has worked with Reddy since 2017.

"There is particular interest in seeing how impacts produce craters. It's also interesting from an orbital prediction perspective, because it's traveling between the Earth and moon unpropelled," Campbell added. "It's just an inert rocket body tossed around by its own energy and by solar radiation pressure, so we can evaluate our models and see how good our predictions are."

The University of Arizona team has also tracked other space objects over the years, including the now-defunct Chinese space station Tiangong 1 that deorbited in 2018, a piece of an Atlas rocket that launched the NASA Surveyor 2 moon mission in 1966, and the 22-ton Chinese Long March 5B rocket that fell uncontrolled back to Earth in 2021.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.