New moon of June 2025 sees Mercury climb to its highest point in the sky

The young moon leaves the sky dark for skywatchers to see Mercury next to our lunar companion on June 27.

The new moon occurs on June 25. A day later, Mercury reaches its highest point in the evening sky, and on June 27, the young moon will make a close pass to the planet.

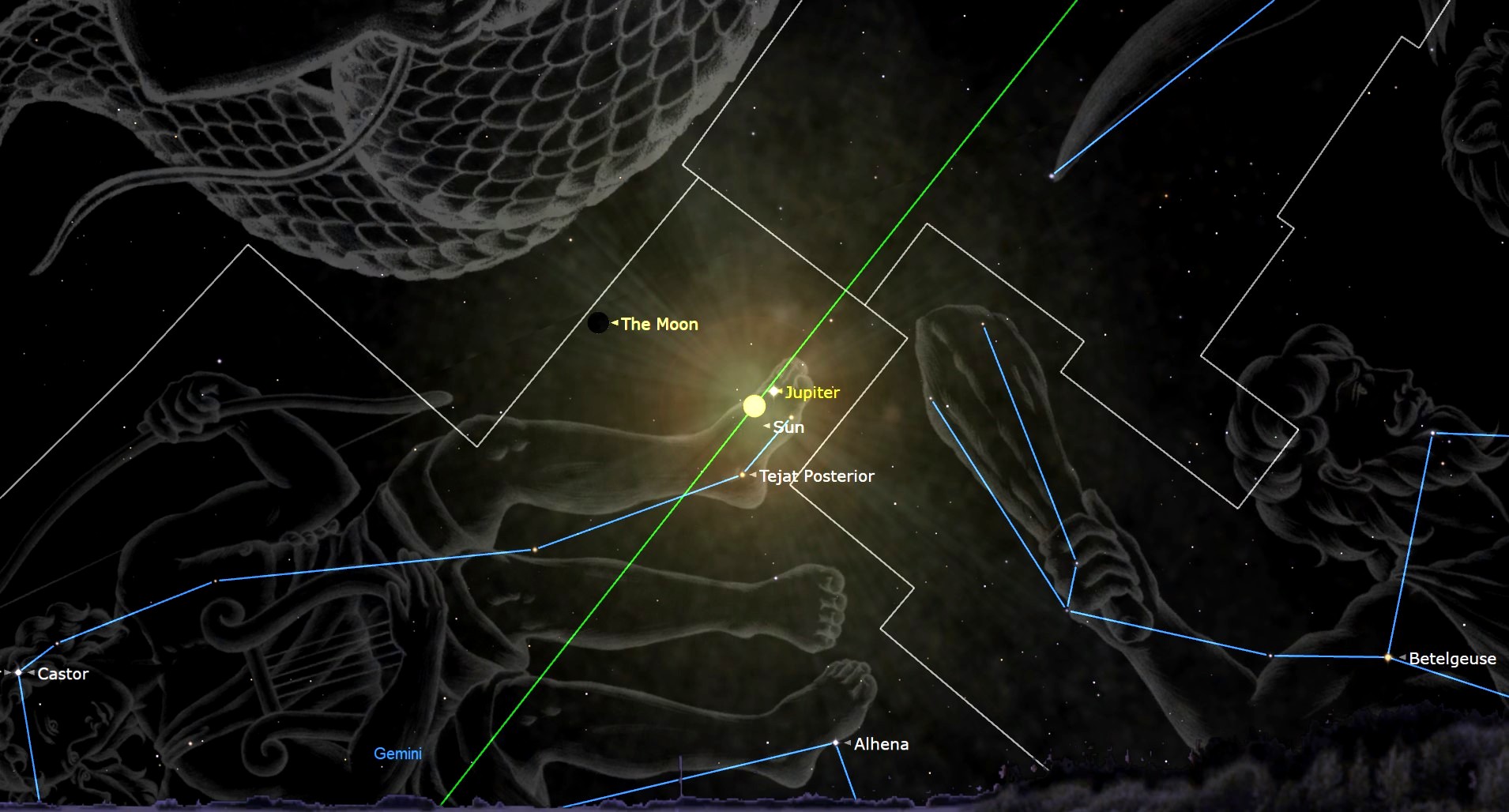

The exact moment of the new moon phase occurs at 6:31 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time (1031 UTC), in New York, according to the U.S. Naval Observatory. A new moon describes the moment when the sun and moon share a celestial longitude (called right ascension by astronomers), a projection of Earth's longitude lines on the sky measured eastward from the point where the sun crosses the celestial equator.

This position is also called a conjunction, and it can only happen when the moon is directly between Earth and the sun.

Sometimes the sun, moon and Earth line up perfectly, and the result is a solar eclipse. No eclipse is scheduled for this new moon, though – the next one is due on Sept. 21. Outside of solar eclipses, new moons are not visible.

Lunar phases are determined by the moon's position in its orbit around Earth, so they occur at the same time everywhere; the difference in the hour is solely due to one's time zone. The new moon thus occurs at 3:31 a.m. in Los Angeles, 11:31 a.m. in Paris, and 7:31 p.m. local time in Tokyo.

Visible planets

On June 25 the sun sets at 8:31 p.m. in New York, according to the U.S. Naval Observatory; just five days after the solstice (June 20), so in the Northern Hemisphere days are still quite long. The sky starts to get dark enough to see bright objects by about 9:15 p.m. At that point, one can see Mercury if there is a clear horizon. From New York City the planet will be about 8 degrees above the horizon; tricky to spot, but still possible if conditions are right.

On June 26, Mercury reaches its highest elevation for Northern Hemisphere observers; at 9:15 it is still about 8 degrees high; that day the moon will be a thin crescent on the right side of the planet. On June 27, in the wee hours of the morning in New York (2:03 a.m.), the moon passes within 3 degrees of Mercury; while the conjunction itself won't be visible (both the moon and Mercury are below the horizon) by the evening the moon will appear to the left of the planet and above it.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mars, meanwhile, will be low in the west, as the planet sinks a bit each day towards the evening sun; by August, Mars will be lost in the solar glare. One can spot it easily by its reddish color; while the planet is not as bright as it can be (it is at a point in its orbit where it is further from Earth) the color remains distinct.

Saturn rises after midnight at 12:48 a.m. EDT, (June 26) followed by Venus at 2:56 a.m. By sunrise at 4:53 a.m. Saturn is at 40 degrees and Venus at about 23 degrees; a good exercise is to see how close to sunrise one can still spot the two planets.

For those located closer to the equator, Mercury is a bit higher; from Bridgetown, Barbados, it is at 22 degrees at sunset (6:28 p.m.) and won't be visible until about a half hour later. The planet sets at 8:10 p.m. June 25. The June 27 conjunction with the moon is more visible as one goes far westwards from New York; in Honolulu, Hawaii, the conjunction is at 8:03 p.m. and Mercury will still be 12 degrees above the western horizon with the thin crescent moon above it at about 22 degrees. In the tropics, the effect of seasons on day length is much less pronounced – sunset on June 25 in Honolulu is at 7:17 p.m., rather earlier than in New York.

From the Southern Hemisphere, Mars will be in the northwest after sunset. As it is the austral winter, sunsets are early. In Santiago, Chile, for example, sunset is at 5:43 p.m. local time on June 25. By 6:30 p.m. local time Mars is 40 degrees above the northwestern horizon in the constellation Leo.

Closer to the horizon is Mercury which, as in the Northern Hemisphere, is a challenge to observe, but it is slightly higher for austral sky watchers; about 10 degrees high, so with a clear horizon and no trees or buildings one can catch it. Mercury sets in Santiago by 7:33 p.m. local time.

In Santiago, Saturn rises on June 26 at 12:48 a.m. Venus rises at 4:20 a.m.; by 6 a.m. Saturn is about 53 degrees high in the north-northeast and Venus is at 20 degrees in the northeast. Sunrise isn't until 7:47 a.m., by 7 a.m. as the sky is getting light one can see Venus in the northeast and Saturn just west of north.

Constellations

In June in the Northern Hemisphere, the sky doesn't get fully dark until about 10 p.m. at the latitude of New York, Denver, San Francisco or Tokyo. In New York City, astronomical twilight, when the sun is between 12 and 18 degrees below the horizon and the last of the daylight disappears, is between 9:47 and 10:37 p.m. on June 25.

At 10 p.m., as one can look south and see the red star Antares, about 21 degrees high; one can distinguish it from Mars because the planet will be in the west (to the right). Another way to know the difference immediately is that on nights when stars visibly twinkle planets shine with a steady light. At this time of year one can see the entirety of Scorpius, the Scorpion, from mid-northern latitudes, though the very end of the Scorpion's tail is brushing the horizon and is only visible if there's nothing in the way. That said, one can easily catch the three stars to the right of Antares that mark the claws.

Turning eastwards (left) and even closer to the horizon one can see the "teapot" shape of Sagittarius the Archer rising; it gets more visible as the night progresses and gets to its highest altitude (about 20 degrees) by about 1 a.m. June 26.

Further left, almost due east at 10 p.m. and about 23 degrees high is Altair, the eye of Aquila the Eagle, which is the southernmost point of the Summer Triangle. The other two are Vega, or Alpha Lyrae, which is upwards and to the left of Altair, more than halfway to the zenith in the east-northeast. The third star is Deneb, the brightest star in Cygnus, the Swan, located a bit higher than Altair and towards the northeast. All three stars form a right triangle shape with the 90-degree corner at Deneb and are bright enough that they are visible even in light-polluted areas.

The Big Dipper, which is a common orientation point for Northern Hemisphere sky watchers, is in the northeast, about two thirds of the way to the zenith from the horizon. At 10 p.m. it will be to the left as one faces north, almost vertical with the bowl on the downward side. On the bottom side of the bowl in this orientation are the stars called Dubhe and Merak that point to Polaris. Dubhe will be on the right; one finds Polaris, the Pole Star, by making a line between the two and continuing until one reaches it. The Big Dipper is not a constellation in itself; it is part of the larger group that is the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. Polaris is the end of the handle of the Little Dipper, the asterism that makes up most of Ursa Minor, the Little Bear.

Following the handle of the Dipper one can "arc to Arcturus" –a sweeping motion along the curve of the handle gets you there, to the brightest star in Boötes, the Herdsman. Continuing that arc one hits Spica, the brightest star in Virgo. If one draws a line between Dubhe and Merak away from Polaris one reaches Leo, the Lion.

Arcturus is high at 10 p.m. – 62 degrees above the southwestern horizon. Looking a bit to the left, one can see an arc of stars with a brighter one at the halfway point of the arc; this is Corona Borealis, the Northern Crown. The bright star Alpha Corona Borealis is called Alphecca; at this point one is looking almost directly overhead.

Further left (east) from Corona Borealis is a square of fainter stars that makes up the central part of Hercules. The square is sometimes called the Keystone. If one moves south (toward the horizon) one meets Ophiuchus, the Serpent Holder, a large and faint constellation above Scorpius. Ophiuchus makes a large, narrow, five-sided shape – rather like a tall A-frame house.

Starting with Antares, if one looks up and to the left of it, there is a star called Pi Ophiuchi, or Sabik, that is the bottom left corner of the main body of Ophiuchus, and to the right and above that is Zeta Ophiuchi. Look slightly to the left and upwards and one sees Kappa Ophiuchi, the right upper corner of the "box" that is Ophiuchus' body (think of it as his shoulder). Look leftward and one sees the slightly brighter star Ras Alhague, Alpha Ophiuchi, the head, and to the left and downward is the other shoulder, Beta Ophiuchi or Cebalrai (pronounced with a hard C).

In the Southern Hemisphere, the sky gets dark enough to see stars by 7:00 p.m. Observers in mid-southern latitudes can see Scorpius 40 degrees high in the east; by 11 p.m. the constellation is almost directly overhead. Looking due south and upwards – two thirds of the way to the zenith – is Crux, the Southern Cross. The cross will be upright, so the bottom star is Acrux (Alpha Crucis), while on the left is Mimosa (Beta Crucis), the top is Gacrux (Gamma Crucis) and the right point is Imai (Delta Crucis).

Draw a line between Imai and Mimosa to the left and one hits Hadar, the second brightest star in Cetaurus, the Centaur. To the left of that and slightly downward is Alpha Centauri, also called Rigil Kentaurus, our nearest stellar neighbor.

Turning right towards the southwest, one can see Canopus at about 25 degrees high; it's the brightest star in Carina, the Ship's Keel. Above Canopus is a large ring of about seven stars (nine from a darker sky location) that is Vela, the Sail.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.