So long, Gaia: Europe officially retires prolific star-mapping space telescope

"We will never forget Gaia, and Gaia will never forget us."

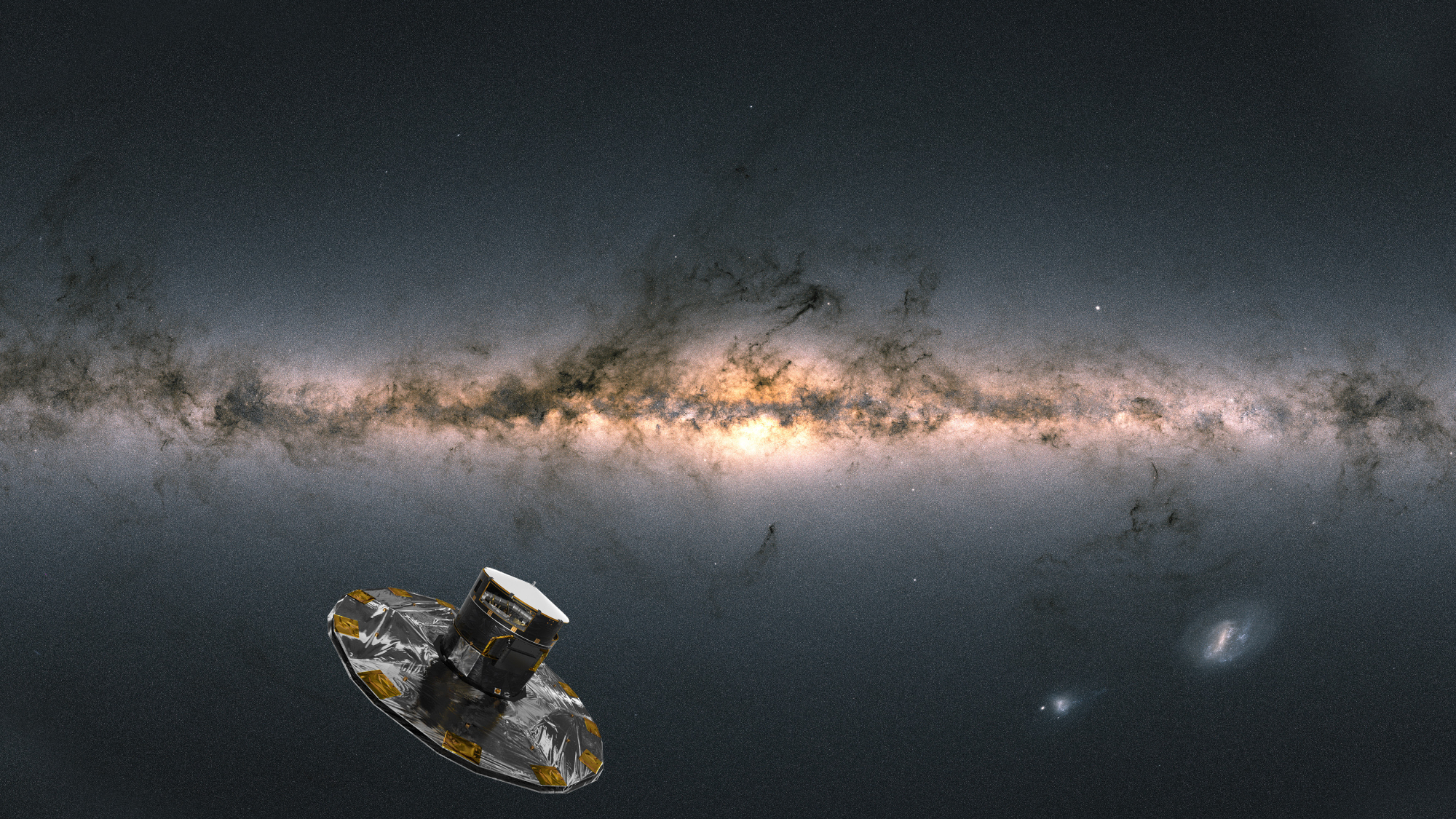

Europe's star-mapping Gaia space observatory has entered its final orbit, after gathering valuable cosmic data for more than a decade.

The spacecraft's control team at the European Space Operations Centre in Paris switched off Gaia's subsystems today (March 27) and sent the venerable craft into a safe "retirement orbit."

"We will never forget Gaia, and Gaia will never forget us," Gaia Mission Manager Uwe Lammers said in a statement.

In January, the European Space Agency (ESA) shut down Gaia's science operations, as the spacecraft's fuel reserves were nearly depleted. This ended Gaia's data collection, but more work was needed to put Gaia to bed.

Related: Goodnight, Gaia! ESA spacecraft shuts down after 12 years of Milky Way mapping

For example, the team needed to move the probe from its science orbit at the Earth-Sun Lagrange Point 2 — a gravitationally stable spot about 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from us — to a retirement orbit around the sun that minimizes the chances Gaia gets within 6.2 million miles (10 million km) of Earth for at least the next century. That was accomplished today via a final firing of the spacecraft's thrusters, team members said.

Though Gaia's work is now officially done, the mission will continue expanding our knowledge of the Milky Way far into the future, team members said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Gaia's extensive data releases are a unique treasure trove for astrophysical research, and influence almost all disciplines in astronomy," Gaia Project Scientist Johannes Sahlmann said in the same statement.

Gaia set out to map the Milky Way after launching in 2013. It charted the positions of nearly two billion stars, providing a precise 3D map of our galaxy.

The mission's accomplishments include discovering evidence of galactic mergers, identifying new star clusters, tracking hundreds of thousands of asteroids and comets, and helping discover exoplanets and black holes.

The Gaia team releases big batches of mission data every couple of years. The three such releases to date occurred in 2016, 2018 and 2022.

"Data release 4, planned for 2026, and the final Gaia legacy catalogues, planned for release no earlier than the end of 2030, will continue shaping our scientific understanding of the cosmos for decades to come," Sahlmann added.

It turns out that ending Gaia's useful life cycle wasn't easy. "Switching off a spacecraft at the end of its mission sounds like a simple enough job," Gaia Spacecraft Operator Tiago Nogueira said in the same release. "But spacecraft really don't want to be switched off."

The observatory was designed to withstand the extreme conditions it would face during spaceflight, such as radiation storms and micrometeorite impacts. To this end, Gaia has built-in redundancies to make sure it could reboot after a disruption.

"We had to design a decommissioning strategy that involved systematically picking apart and disabling the layers of redundancy that have safeguarded Gaia for so long," Nogueira added, "because we don't want it to reactivate in the future and begin transmitting again if its solar panels find sunlight."

This was a sobering and bittersweet task, team members said.

"Today, I was in charge of corrupting Gaia's processor modules to make sure that the onboard software will never restart again once we have switched off the spacecraft," Spacecraft Operations Engineer Julia Fortuno said in the same statement.

"I have mixed feelings between the excitement for these important end-of-life operations and the sadness of saying goodbye to a spacecraft I have worked on for more than five years," Fortuno added. "I am very happy to have been part of this incredible mission."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Julian Dossett is a freelance writer living in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He primarily covers the rocket industry and space exploration and, in addition to science writing, contributes travel stories to New Mexico Magazine. In 2022 and 2024, his travel writing earned IRMA Awards. Previously, he worked as a staff writer at CNET. He graduated from Texas State University in San Marcos in 2011 with a B.A. in philosophy. He owns a large collection of sci-fi pulp magazines from the 1960s.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.