Can SpaceX's Starlink sue Russia for anti-satellite missile test space debris fallout?

Is cluttering space with junk from anti-satellite missile tests legally punishable?

Experts agree that the Russian anti-satellite missile test that shattered into pieces the defunct surveillance satellite Cosmos 1408 on Nov. 15. will cause headaches to operators of low Earth orbit satellites for years. Can they hold the culprit accountable?

According to Christopher Johnson, a space law adviser at the Secure World Foundation, a private organization dedicated to the sustainable use of space, Russia's act is akin to releasing a toxic chemical into the ocean. Everybody who flies satellites in the affected patch of space is now left to deal with the fallout — the cloud of over 1,500 pieces of space debris larger than 4 inches (10 centimeters) and thousands of smaller fragments that can't be tracked from Earth. These fragments hurtle through space at speeds of 15,700 mph (25,000 kph) completely out of control, threatening everything in their path.

Among those at risk is the International Space Station, where the seven astronauts on board had to shelter from debris shortly after the ASAT test, and SpaceX's Starlink megaconstellation of nearly 2,000 internet-beaming satellites.

The anti-satellite test, Johnson told Space.com, is likely a breach of a piece of international space law called the United Nations Outer Space Treaty, which binds countries that fly anything in space to use space responsibly and in harmony with others.

Article IX of the treaty, which was signed in 1967, urges countries to cooperate and assist each other in their endeavors in space, avoid harmful contamination of the space environment and not interfere with the interests of other spacefaring nations.

Related: Kessler Syndrome and the space debris problem

"I would say a state can already make a claim that Russia has not shown due regard to the corresponding interests of other states," Johnson told Space.com. "It has not adhered to those principles of cooperation and mutual assistance in Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty. It has not taken precautions to prevent the harmful contamination of outer space, which is an obligation that it has, and further it has actually caused harmful contamination of outer space."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Russia's predecessor, the Soviet Union, was among the first signatories of the Outer Space Treaty at the height of the Cold-War era space race.

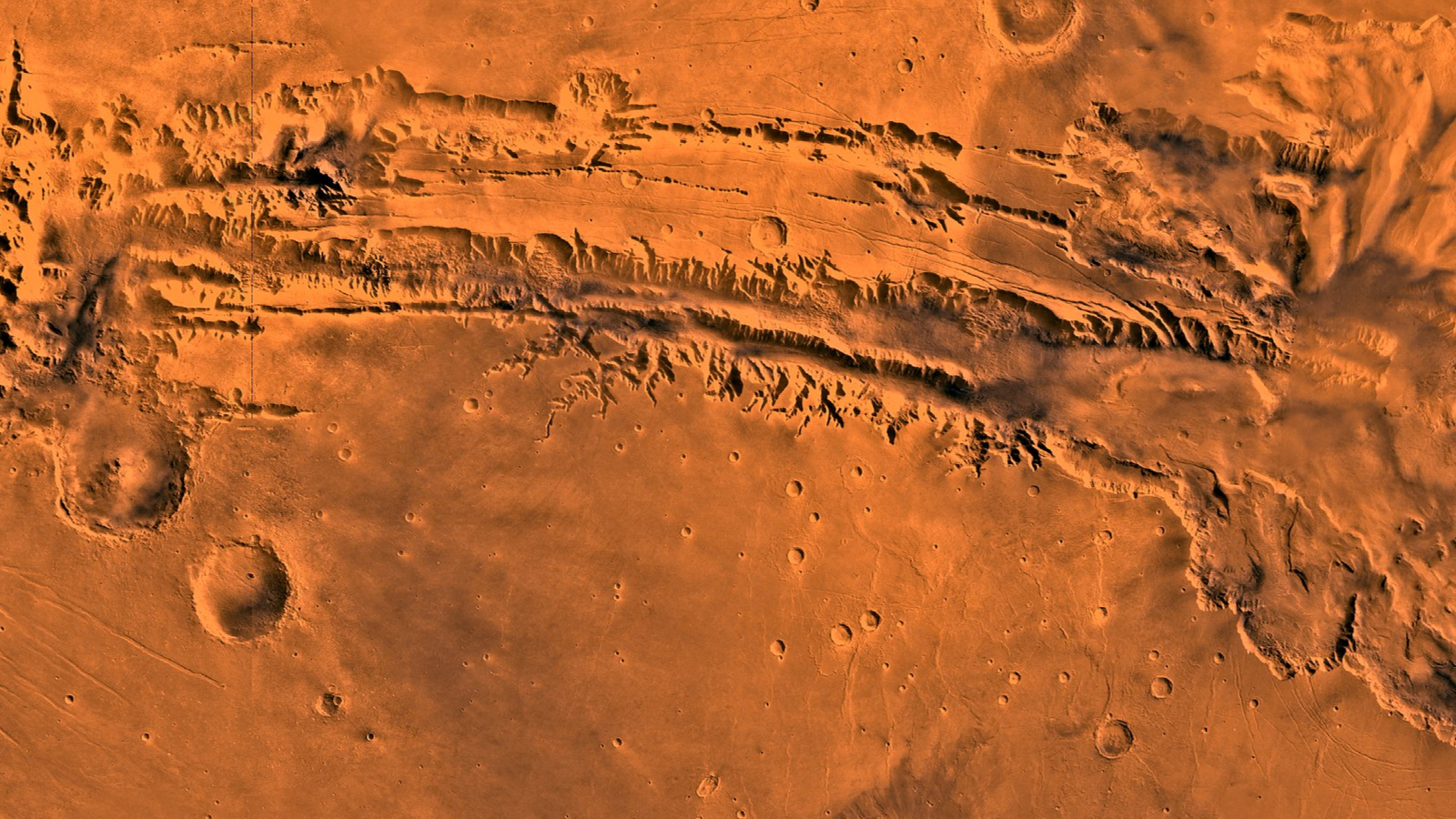

Over 50 years later, Russia chose to show off its satellite-destruction skills on a target situated right in the middle of one of the most heavily used portions of space near Earth. Cosmos 1408 orbited at an altitude of about 290 miles (470 kilometers), just 25 miles (40 km) above the space station. Starlink satellites orbit at 340 miles (550 km). There are many others, including, for example, a couple of hundred spacecraft of Earth observation company Planet, which fly between 280 and 310 miles (450 and 500 km).

Twice as many avoidance maneuvers

All these operators will now have to perform more than twice as many space junk avoidance maneuvers than before, Tim Flohrer, head of the European Space Agency's (ESA) space debris office, told Space.com shortly after the antisatellite test.

"The workload will certainly increase," Flohrer said. "In particular for everything up to the 600-kilometer [370 miles] orbit."

More avoidance maneuvers mean that satellites will run out of fuel faster and spend more time off, not providing the service they had been designed for, as they have to be shut down during the maneuvers. Ironically, the burden to prevent further collisions and the creation of further orbital debris is now on the shoulders of these satellite operators, who will have to regularly summon expert teams to navigate these treacherous encounters. How could they hold the real culprit accountable?

"It would really not be in their best interests, short-term or long-term, to set the precedent that they are not going to complain," Johnson said. "Their business case and their operations are really prejudiced by this debris cloud, even if they can predict it perfectly. If they have to continue performing maneuvers to get away from debris, I think that could severely impact their business."

A precedent

The legal basis for making a claim against Russia is not straightforward. In 1972, the U.N. negotiated an addition to the Outer Space Treaty, the Liability Convention, which states that every state that flies anything in space is absolutely liable for any damage it causes on Earth, in the air above it, or in space.

So far, this liability has only been called upon once. In 1978, Russia agreed to pay 3 million Canadian dollars ($2.36 million) after remnants of its reconnaissance satellite Cosmos 954 survived the atmospheric re-entry and scattered highly radioactive material along a 370-mile-wide (600 km) patch of northern Canada.

But no one has ever made anyone yet pay for damages caused in space. Despite the international outcry, China got away with generating the largest ever cloud of space debris in history with an anti-satellite missile test in 2007. Fragments from this incident are still the biggest threat for spacecraft in near-Earth space. Two years later, Russia's defunct satellite Cosmos 2251 collided with the U.S. commercial telecommunications satellite Iridium 33. The collision produced another massive cloud of debris that clutters the orbit to this day. In this case, too, nobody paid.

The cost of constant dodging

Ram Jakhu, an expert in international space law and a lecturer at McGill University in Montreal, says that the Liability Convention is mostly understood to cover actual physical damage to a satellite. If a piece of debris generated by the Russian ASAT test destroyed a Starlink satellite, for example, SpaceX could ask the U.S. government to request the government of Russia to pay for the damage on the company's behalf. But as long as Starlink and all other operators manage to keep dodging the junk, compensation for the financial damage caused by this constant need to maneuver would be more difficult to exact.

"It is possible but very difficult," Jakhu told Space.com. "The [physical damage] scenario is relatively easy because it is relatively easy to prove who caused the damage. That needs to be established before a claim is made. The [economic damage] scenario would be more difficult to prove."

Johnson, however, thinks the aftermath of this incident may set a new precedent, expanding the traditional understanding of 'damage' to include the economic impacts of avoiding space debris.

"We often think that liability for damages under space law requires physical damage," Johnson said. "But views on that are evolving and just monetary and operational damage might also be included as a compensable harm."

Where to take the case?

So if all those agencies and operators affected by the Russian antisatellite demonstration want to hold the culprit accountable, where would they go? First, Johnson said, to their respective governments, which might then take the case to global institutions headquartered at the Hague: either to the International Court of Justice for a public hearing or to the International Court of Arbitration, where it would be dealt with behind closed doors. The situation could also be dealt with in diplomatic discussions between states.

Regardless of the venue, the important thing, Johnson added, is for the victims to speak up about the harm. "They should be letting the world know if they have to perform maneuvers — how much it costs to do that, how much their operational lifespan is decreased because of that," Johnson said. "Let the world know how you're being affected. I think that's a responsible thing to do, to be transparent about how you're being impacted."

Ignoring the space debris problem

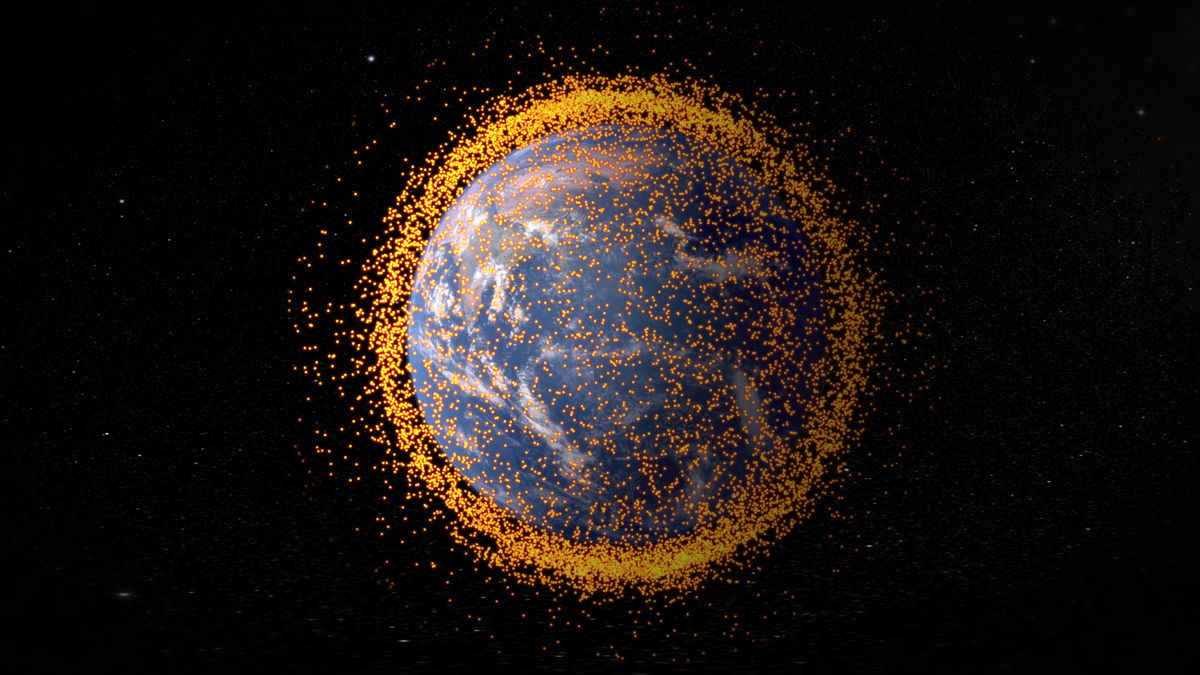

In recent years, experts from all over the world have been increasingly calling for stricter space junk prevention measures. More and more satellites are being launched and with that, the risk of space collisions grows. There are currently about 3,000 defunct satellites zooming around Earth, according to ESA.

Spent rocket stages that lofted those satellites also remain in orbit and occasionally explode, generating masses of fragments. Collisions between space debris and old satellites spawn further clutter. ESA estimates that all told, space around Earth hosts a staggering 36,500 pieces of junk larger than 4 inches (10 centimeters), 1 million pieces between 0.4 inches and 4 inches (1 to 10 cm) across, and 330 million pieces that are smaller than 0.4 inches (1 cm) but bigger than 0.04 inches (1 millimeter). Each of these fragments is capable of destroying or at least significantly damaging a satellite.

In August 2016, a fragment of space junk less than 0.2 inches (5 mm) in size smashed through the solar panel of the European Earth-observing Copernicus Sentinel-1A satellite, causing immediate loss of power. The spacecraft recovered from the incident and continues its mission to this day. But the mission's operators said the consequences would have been much more severe had the main body of the spacecraft been hit.

And the risk of such accidents will increase for at least the next decade as a result of the Russian ASAT test, according to Flohrer.

Eventually, the debris from the ASAT test will succumb to the drag of Earth's residual atmosphere, its orbit will decay and it will burn up while falling to Earth. Depending on the altitude to which these fragments had been sent when the missile broke up Cosmos 1408, this natural clean-up process may take years or decades. By then, the fragments may have caused many more collisions.

"I think everyone has always said 'do we need an accident on orbit, a collision on orbit, a catastrophe on orbit before we get serious?'," said Johnson. "Maybe this will be the thing that gets us serious about everything, and it hasn't caused damage yet. It hasn't caused the collision yet, but maybe this will be the instigating incident for people to actually get serious."

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.