Asterisms: Definition, facts and examples

Though unofficial, the patterns of stars forming asterisms are thrilling targets for astronomers

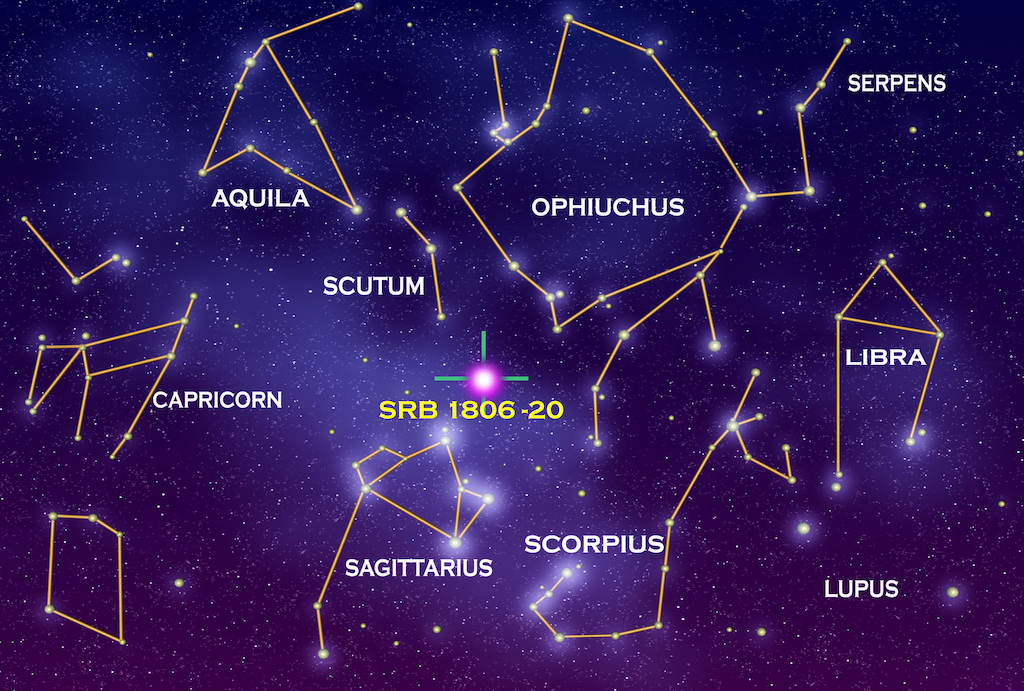

With billions of stars visible from Earth, cataloging asterisms provides beneficial reference points in the night sky. And throughout history, this cataloging process, which still only encompasses a tiny fraction of the stars in the night sky, has been guided by our myths and legends, as well as the objects and creatures that populate our terrestrial lives.

But, while most of us are familiar with the constellations, even if this familiarity comes from the Zodiac signs that share their names with many of them, there is another visual classification of star arrangements. Seemingly less familiar to the general public, astronomers know just how important and fascinating these arrangements, known as asterisms, are.

According to NASA, there are 88 officially recognized constellations, 48 of which date back to ancient civilizations like the Babylonians and the Greeks and even earlier, with later “modern” constellations added as humanity’s exploration of the night sky grew more precise.

These constellations and their names bear the imprint of our culture with names that reflect the patterns or pictures they seem to form. Though many cultures have had their own names for the constellations, the designations western astronomers are most familiar with are those of Greek mythology.

Thus we have constellations like Orion the Great Hunter, comprised of stars forming the stick figure of a man wielding a sword and shield, named after a Greek mythical figure with the blood of the Gods flowing through his veins.

Related: The Little Dipper: Host of the North Star

The more modern constellations, identified by later astronomers of the 1500s, 1600s, and 1700s who could use optical devices to search the skies and had access to the southern hemisphere, take their names from less fantastical things like animals and devices like peacocks, giraffes, and telescopes.

What is interesting about the constellations and asterisms, is they are totally unique to our view from Earth. Selected due to their projected proximity on the 2D sphere of the sky as it surrounds Earth, the stars of the constellations may actually be separated by vast cosmic distances.

For instance, the stars that make up the tiny constellation Triangulum exist at distances of between 35 and 127 light-years from Earth.

The stars in asterisms often share this almost arbitrary relationship to one another, but occasionally, the connection between these stars runs deeper than just how and where they appear to us.

Asterisms defined

Asterisms are patterns of stars with shapes and sizes that can range from the very simple, containing just a few stars, to the larger and more complex — with some of these arrangements of stars covering large regions of the sky.

Stars within an asterism are usually of similar brightness to each other and might range from bright and visible to the naked eye or distinguishable with a telescope, Space.com previously reported. In terms of relationships to each other; stars in an asterism may have a physical connection or maybe completely random groupings.

One of the most famous conglomerations of stars in the Big Dipper or the Plow (or Plough depending on the region of the world you live). Comprised of the seven brightest stars of the constellation Ursa Major — or the Great Bear — the Big Dipper isn’t a constellation at all but is an asterism.

Five of the stars that make up the Big dipper are part of the Ursa Major Moving Group, or Collinder 285. This is the closest set of stars to Earth with common velocities in space that are believed to have a common origin in space and time.

On the other hand, the stars that make up the asterism “the Coathanger” — which forms the main part of Brocchi’s cluster or Colnder 399 — have provided a controversial example of the relationships between stars in an asterism, or the lack of the same.

Originally, these stars were believed to all be part of an open cluster, formed from the collapse of the same tremendously massive and dense cloud of molecular gas. As a consequence, they would all have similar ages.

Related: What's the story behind the stars?

Research conducted in the 1970s revealed however that only 6 of the brightest stars in the Coathanger were part of an open cluster. This has been revised several times since 1998 and it is now consensus that the stars are a random alignment with no physical links.

Likewise, the three stars that make up the asterism the Summer Triangle — a large triangle of stars easy to observe in the east on summer evenings in the northern hemisphere — have no actual physical relationship to each other.

Asterisms may not always even be located within the same constellation, so considering them as a "sub-division" of constellations doesn’t really work.

One interesting example of a cross-border asterism is the Lozenge. This diamond is composed of three stars from the head of Draco — Eltanin, Grumium, and Rastaban — and one from the foot of Hercules. One almost wonders what tales the Greeks could have come up with if they had spotted this asterism.

What's the difference between an asterism and constellation?

Like constellations, asterisms are stars that join together to trace out pictures of familiar objects in the sky.

One of the main distinctions between constellations and asterisms is the latter are relatively new, while the former, as mentioned above often date back to ancient times.

Nor are their boundaries officially designated as is the case with constellations. This means that an asterism could be any loose association of stars that seem to come together to form a picture, figure, and representation of something recognizable.

But this recognition of "official" boundaries to the constellations is a surprisingly recent thing, as is the delineation between constellations and asterisms. Despite humanity’s long history of stargazing, constellations and asterisms would not be clearly separated until well into the 20th century.

This separation of constellations and asterisms into their own categories occurred in 1928 when the International Astronomical Union and Belgian astronomer Eugène Joseph Delporte set about formalizing the number of constellations and their boundaries.

At the head of his report, Scientific Demarcation of the Constellations, published in 1930, Delporte wrote: "In their descriptions, the ancients left us a star-studded sky divided into asterisms, but without any clear-cut boundaries."

He went on to explain why such a delineation was overdue: "The precise demarcation of the constellations is of utmost importance for a great deal of astronomical work such as the systematic observation of meteors, the study, and denomination of variables, the observation of novae, etc."

Asterisms may not be "officially recognized" like the constellations, and their boundaries are not as clearly defined, but they provide no less intriguing and tempting targets for the observations of astronomers.

Asterisms have become important tools for star-gazers, providing good visual guides to help them navigate the night sky. Smaller and less overwhelming than the constellations, asterisms are especially important for young and beginner astronomers, thus ensuring that further generations continue to project their creativity and imagination of the heavens just as our ancestors did.

The Big Dipper and Little Dipper

Possibly the most well-known asterisms are the seven brightest stars of Ursa Major (the Great Bear) that make up the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper located in the constellations of and Ursa Minor (the little bear). Easy to observe, these asterisms can be seen close together in the sky over the Northern Hemisphere. You can read about the stars in the Big Dipper in the interactive image below.

The Southern Cross

The Southern Cross is a cross or kite-shaped arrangement of four bright stars that lies at the center of the constellation Crux. This asterism has been used as navigation for explorers in the south just as Polaris is used in the north.

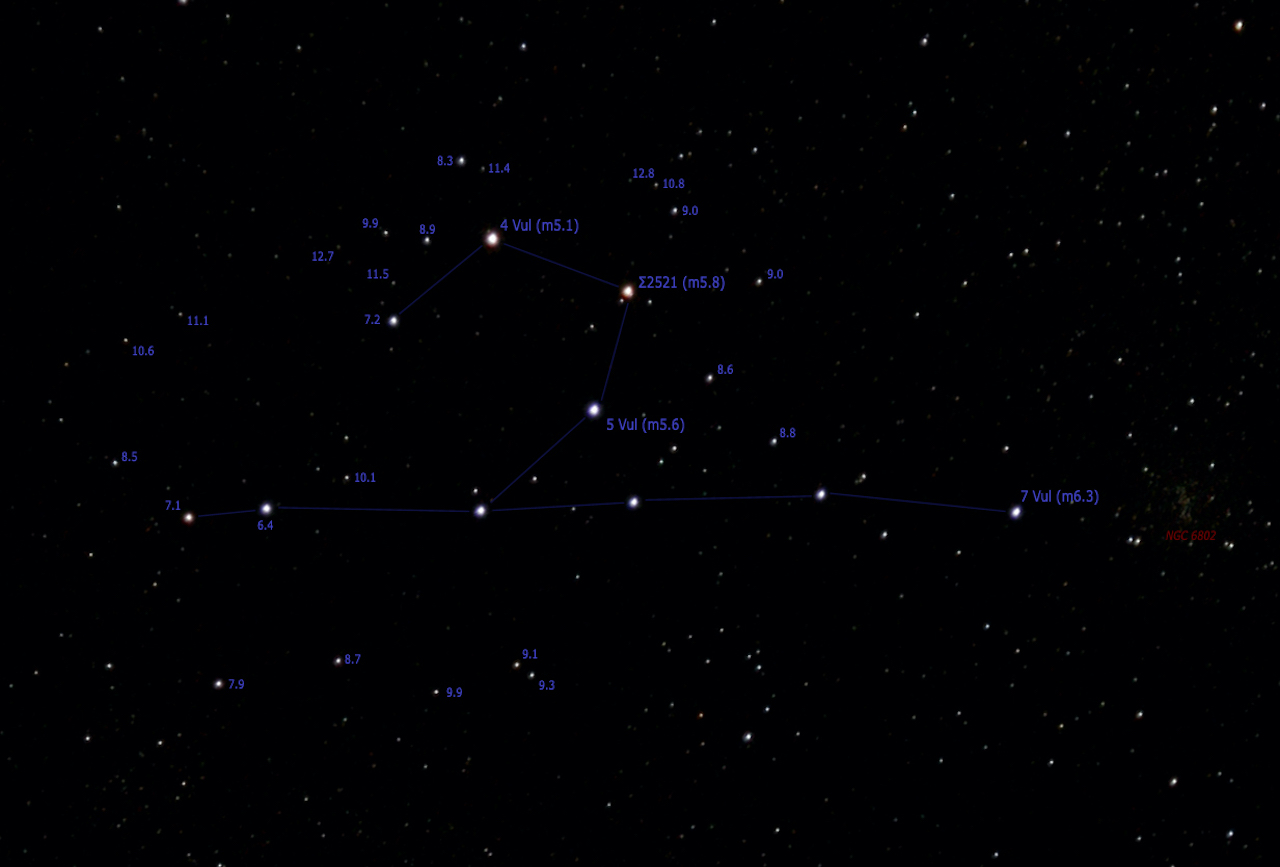

The Coathanger

Made up of 10 bright stars from the Brocchi’s Cluster first described in 964 A.D. Six of the stars form the "hanger" section of the shape, while the other four make up the "hook" element. Best seen from July to August, the Coathanger can be viewed by sweeping between the bright stars of Altair and Vega.

Additional resources

The International Astronomical Union recognizes 88 constellations. For more information about each of these, check out the list of constellations. For this month's skywatching tips and highlights, you can use NASA's monthly skywatching summary.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.