Why is there water on Earth?

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Laurette Piani, Cosmochimiste, chargée de recherche CNRS au Centre de Recherches Pétrographiques et Géochimiques (CRPG) de Nancy, CNRS, Université de Lorraine

Guillaume Paris, Géochimiste, chargé de recherche CNRS au Centre de recherches pétrographiques et géochimiques de Nancy, Université de Lorraine

Water is essential to life as we know it and it seems completely normal to have water all around us. Yet Earth is the only known planet to be covered by oceans. Do we know exactly where its water came from?

This is not a simple question: it was long thought that Earth formed dry — without water, because of its proximity to the Sun and the high temperatures when the solar system formed. In this model, water could have been brought to Earth by comets or asteroids colliding with the Earth. Such a complex origin for water would likely mean that our planet is unique in the universe.

However, in a 2020 study, we showed that water — or at least its components, hydrogen and oxygen — may have been present in the rocks that initially formed the Earth. If that is so indeed, other "blue planets" with liquid water are more likely to exist elsewhere.

Water on Earth, water inside the Earth

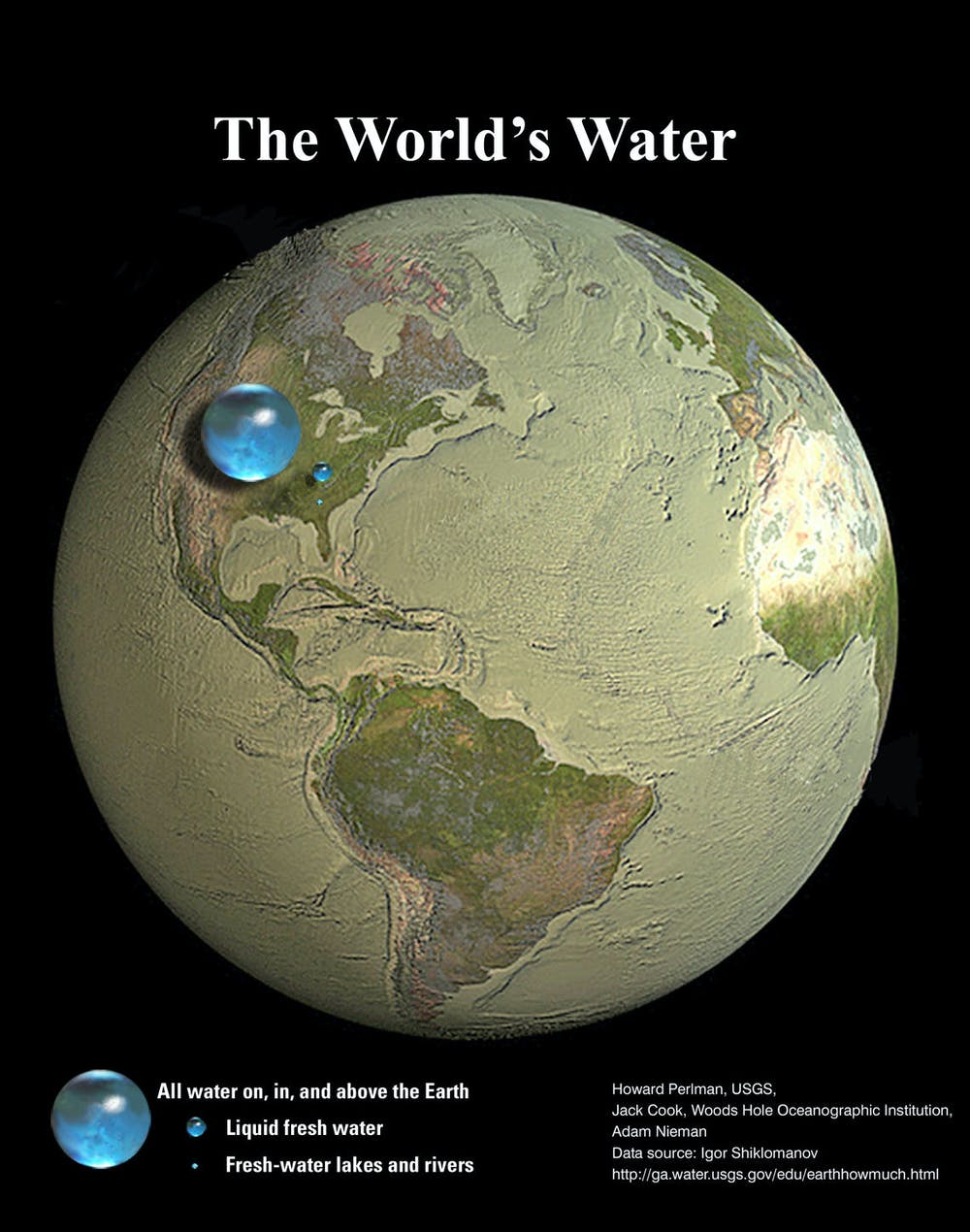

Liquid water covers more than 70% of Earth's surface, with about about 95.6% of it in oceans and seas, and the remaining 4% in glaciers, ice caps, groundwater, lakes, rivers, soil humidity, and the atmosphere.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But most of Earth's water is deep underground: between one and ten times the volume of the oceans are contained in the mantle.

At the surface of the Earth, "water" means two hydrogens for each oxygen (H20), whereas what we call "water" in the mantle corresponds to hydrogen incorporated in minerals, magmas and fluids. This hydrogen can bond with surrounding oxygen to form water at the appropriate temperature and pressure conditions.

While water represents less than 0.5% of the mass of the Earth, it is key to the evolution of the planet itself and to life at its surface.

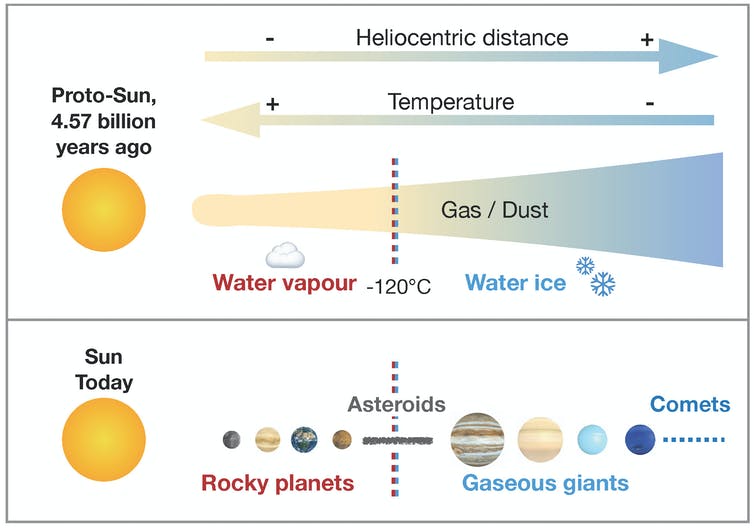

In the early solar system, there was a lot of hydrogen, mainly in the form of dihydrogen gas (H2), or bonded with oxygen atoms to form water (H2O). However, Earth and the other rocky planets (Mercury, Venus, and Mars) formed near the sun, where it was too hot for water to incorporate into rock as ice: it just would have evaporated. So why does the Earth now have so much water, both in its mantle and on its surface?

The prevalent hypothesis: hydrogen delivered to Earth by hydrated asteroids

Some meteorites, called chondrites, come from small asteroids that, unlike the planets, have not geologically evolved since their formation. They are good witnesses of the first millions of years of the solar system.

The carbonaceous chondrites for instance formed far enough away from the Sun to initially contain water ice (all of which has since been incorporated in hydrated minerals through hydrothermal alteration). Contrastingly, ordinary and enstatite chondrites formed closer to the sun where water was gaseous and was incorporated in large amounts into rocks: like the rocky planets, ordinary and enstatite chondrites are considered to be "dry."

Until now, the accepted hypothesis was that Earth formed from dry materials, and that its water was delivered by celestial bodies that formed further from the sun: hydrated meteorites, such as carbonaceous chondrites, or comets — although this last hypothesis was recently thwarted by the ESA space probe Rosetta.

Another origin for Earth’s water?

Our study tells a different story. We analyzed the hydrogen in enstatite chondrites. Remember that these are among our best analogues for the rocks that formed Earth, so the hydrogen concentrations in these "dry" rocks hint at the possible presence of water during Earth’s formation.

We compared the Earth composition and that of enstatite chondrites by looking at the amounts of various isotopes (atoms of the same element but containing different numbers of neutrons). We find that, although enstatite chondrites do not contain hydrated minerals, they do contain small amounts of hydrogen with an isotopic ratio consistent with the Earth's. Hydrogen is thought to have been present in trace amounts (<0.1%) in the minerals and organic compounds that agglomerated to form enstatite chondrites, explaining where most of the water contained in Earth's mantle and in part of the oceans comes from. The majority of Earth's water (more precisely its elements, hydrogen and oxygen) may thus have been present from the beginning.

What are the consequences of a local origin of water?

This does not tell us when the oceans appeared on Earth's surface, but we now know that Earth's water was not necessarily delivered by hydrated bodies that formed very far from the sun. However, we do not yet understand in what form(s) and by what process hydrogen was incorporated and stored in rocks of the inner solar system.

Read more: Why is the Earth blue?

The presence of hydrogen in inner solar system rocks is particularly important because it could have been a water source for the other rocky planets (Mercury, Venus, and Mars). Similar rocks could then represent a source of water for planets orbiting other suns, a condition to develop life, at least life as we know it.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.