Hidden Black Holes Finally Found

A host of hidden black holes have been revealed in a narrow region of the sky, confirming astronomers' suspicions that the universe is loaded with many undetected gravity wells.

Black holes cannot be seen directly, because they trap light and anything else that gets too close. But astronomers infer their presence by noting the behavior of material nearby: gas is superheated and accelerated to a significant fraction of light-speed just before it is consumed.

The activity releases X-rays that escape the black hole's clutches and reveal its presence.

The most active black holes eat so voraciously that they create a colossal cloud of gas and dust around them, through which astronomers cannot peer. That sometimes prevents observations of the region nearest the black hole, making it impossible to verify what's actually there.

These hyperactive black holes are called quasars. They can consume the mass of a thousand stars a year and are thought to be precursers to large, normal galaxies. The exist primarily at great distances, seen as they existed when the universe was young.

A few quasars have been identified, but many more are thought to await discovery, based on the total number of X-rays detected in broad sky surveys.

"From past studies using X-rays, we expected there were a lot of hidden quasars, but we couldn't find them," said study leader Alejo Mart'nez-Sansigre of the University of Oxford, England.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

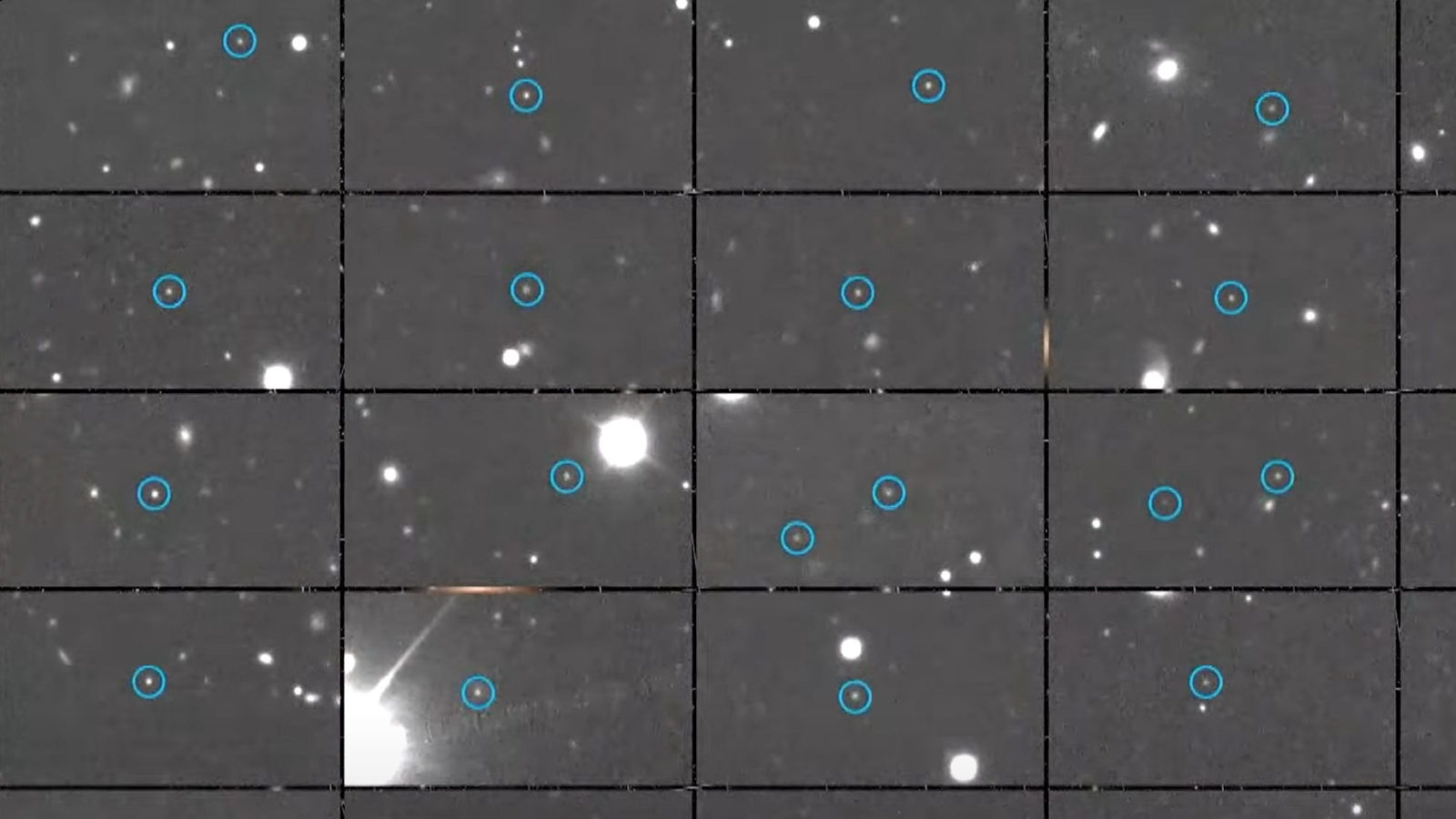

New observations with NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope cut through dust to spot quasars blocked by their own clouds, as well as other quasars hidden inside galactic dust.

Spitzer records infrared light, which penetrates dust. It found 21 quasars in a small patch of sky.

"If you extrapolate our 21 quasars out to the rest of the sky, you get a whole lot of quasars," said study team member Mark Lacy of the Spitzer Science Center at the California Institute of Technology. "This means that, as suspected, most super-massive black hole growth is hidden by dust."

The results are detailed in the Aug. 4 issue of the journal Nature.

- Quasar Jets Create Cosmic Pileups

- Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Quasar

- Lab Device Mimics Black Hole Jets

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.