Distant Galaxies Confirm Accelerating Growth of Universe, Dark Energy

The pesky reality that the universe's expansion is accelerating — an observation that prompted astronomers to invoke an unknown entity called dark energy to explain it — has been further confirmed by new measurements.

Scientists have used cosmic magnifying glasses called gravitational lenses to observe super-bright distant galaxies, giving a measure of how quickly the universe is blowing up like a giant balloon. They found, in agreement with previous measurements, that the universe's expansion is indeed speeding up over time.

The first measurement of this phenomenon, based on exploding stars called supernovae, was made in the 1990s.

"The accelerated cosmic expansion is one of the central problems in modern cosmology," Masamune Oguri, of the University of Tokyo's Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe, said in a statement. "In 2011 the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to the discovery of the accelerated expansion of the universe using observations of distant supernovae. A caution is that this method using supernovae is built on several assumptions, and therefore independent checks of the result are important in order to draw any robust conclusion."

Scientists still don't have much of an idea why the universe is not only expanding doing so ever-faster. The gravity of all the mass in the universe would be expected to pull everything back inward, so scientists call whatever force is counteracting gravity "dark energy."

"Our new result using gravitational lensing not only provides additional strong evidence for the accelerated cosmic expansion, but also is useful for accurate measurements of the expansion speed, which is essential for investigating the nature of dark energy," Oguri said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ogiri led the new study of quasars with Naohisa Inada at Japan's Nara National College of Technology.

Quasars are objects bright enough to be spotted halfway across the universe. They are thought to be powered by hungry black holes that gobble up copious amounts of matter in the centers of galaxies, releasing radiant jets of light that shoot out into space.

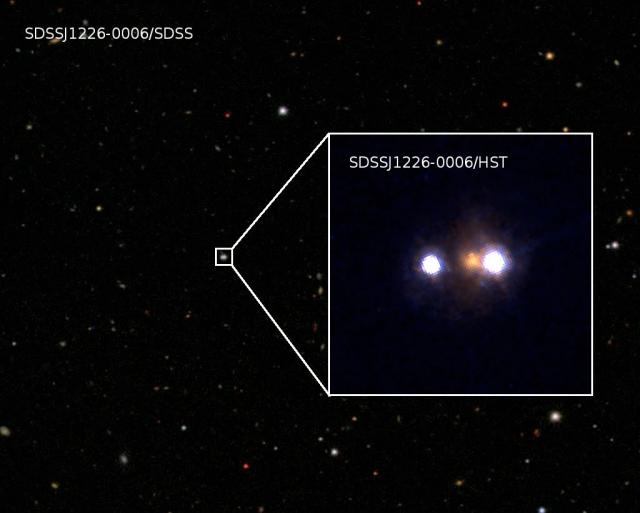

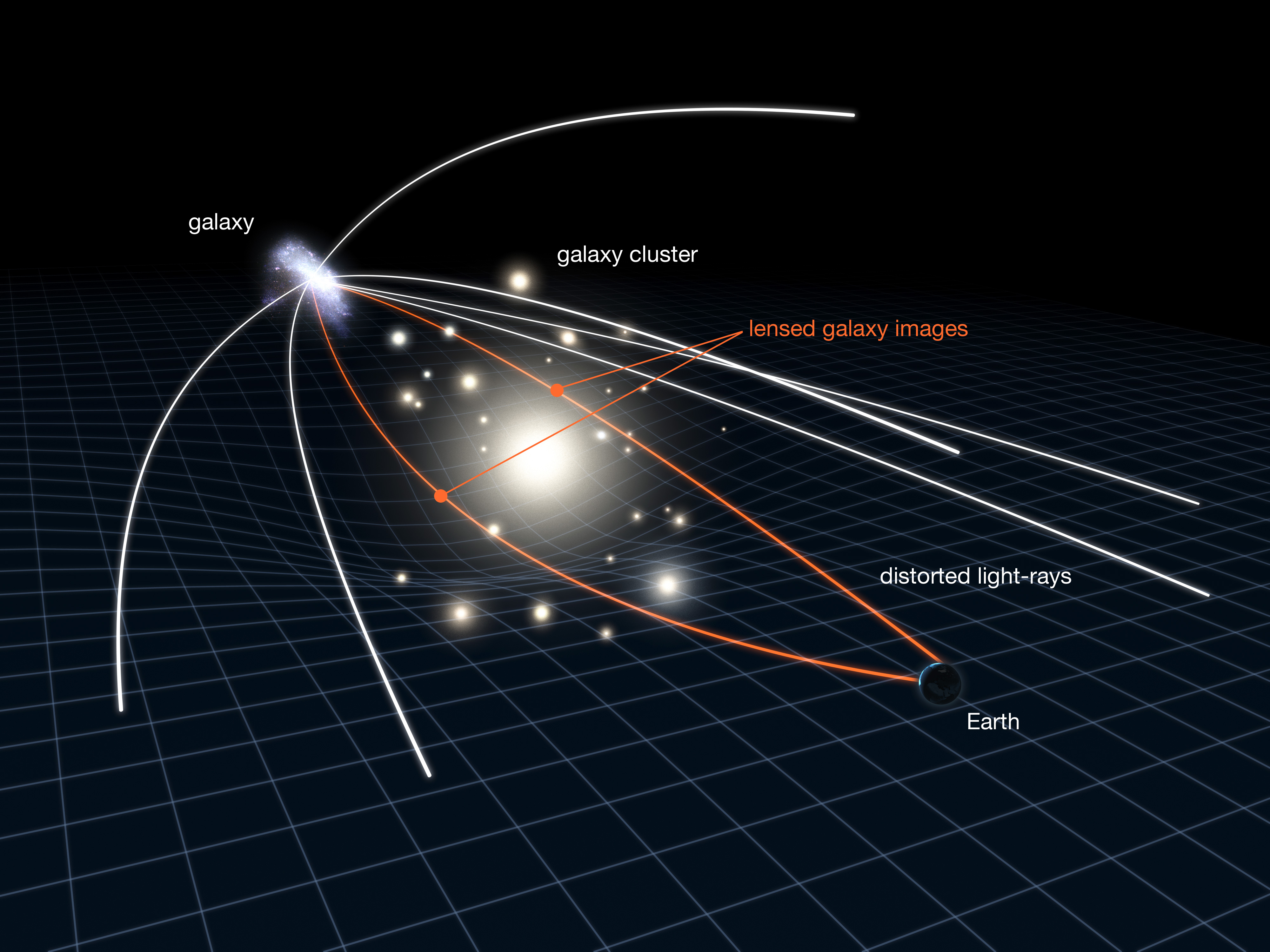

The light from quasars sometimes passes by massive objects on its way to telescopes on Earth, and the gravity from these objects bends space-time, causing the light to travel along a curved path. This can produce warped and distorted double images of a single distant quasar. [Video: Quasar Details Seen With Gravitational Lenses]

As the universe expands, the distance to quasars increases, and so do the chances that a quasar's light will pass by a massive object and be gravitationally lensed.

Thus the frequency of gravitationally lensed quasars can indicate the expansion speed of the universe.

Ogiri, Inada and their colleagues searched for such quasars in the catalog of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), which took detailed observations of giant swaths of the night sky. In a collection of about 100,000 quasars, the researchers identified 50 that were being gravitationally lensed, significantly increasing the known total sample of these objects.

The researchers used their calculation of the frequency of gravitationally lensed quasars to deduce that the universe's expansion is indeed accelerating.

The new results will be reported in an upcoming paper published in the Astronomical Journal.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.