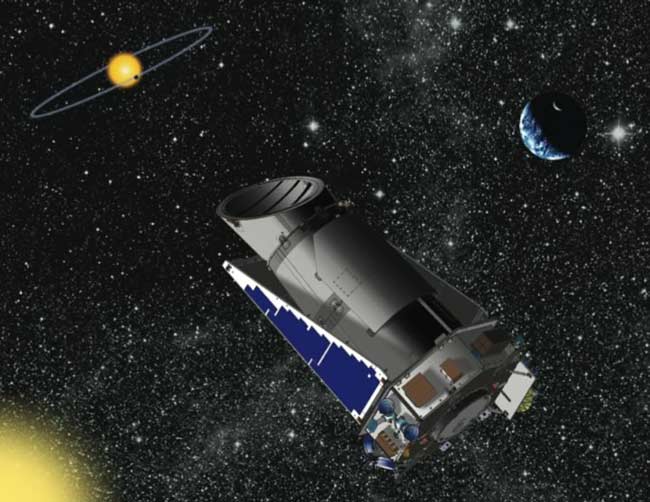

NASA's prolific planet-hunting Kepler space telescope has been placed in a precautionary "safe mode" after engineers noticed a problem with the instrument's orientation mechanism.

The Kepler telescope went into safe mode on Jan. 17 for a planned 10 days, during which time the telescope's reaction wheels — spinning devices used by the observatory to maintain its position in space —will be rested. The move comes after researchers detected an unexpected increase in the amount of torque needed to rotate one of the wheels, mission officials said.

"Resting the wheels provides an opportunity to redistribute internal lubricant, potentially returning the friction to normal levels," Kepler officials wrote in a Jan. 17 mission update.

Kepler will not make any new science observations for its search for alien planets while in safe mode, team members said.

"Once the 10-day rest period ends, the team will recover the spacecraft from this resting safe mode and return to science operations," Kepler officials wrote. "That is expected to take approximately three days. An update will be posted after the wheel rest operation is complete." [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

When the Kepler spacecraft launched in March 2009, it had four functional reaction wheels — three for immediate use, plus one spare. The wheels help the telescope keep its precise aim at more than 150,000 target stars, which it monitors for the presence of orbiting exoplanets.

One of the wheels failed last July. Since the spacecraft needs three functioning reaction wheels to work properly, another failure could potentially end the $600 million Kepler mission.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kepler detects alien planets by flagging the telltale brightness dips caused when they cross the face of their parent stars from the instrument's perspective. Kepler generally needs to witness three such "transits" to identify a planetary candidate.

The telescope has already spotted more than 2,700 potential planets, including a number in their host stars' habitable zones — that range of distances that could support liquid water on a world's surface. To date, just 105 of these candidates have been confirmed, but mission scientists think at least 90 percent should end up being the real deal.

If the three remaining reaction wheels keep spinning normally and Kepler doesn't suffer any other major issues, it could keep scanning its patch of sky for several more years to come. Last year, NASA announced that it had extended the mission through at least 2016.

Kepler's main mission is to find Earth-size planets in the habitable zone. The longer it runs, the more such worlds it will find.

Because of the three-transit requirement, most of the planets Kepler has found so far zip around their stars relatively quickly, in close-in orbits.

With more time, the instrument will be able to discover more exoplanets in relatively distant orbits, allowing Kepler to survey the habitable zones of warmer stars. (It could take a hypothetical alien version of Kepler up to three years, after all, to see Earth transit the sun three times.)

Witnessing more transits will also increase the signal-to-noise ratio, enabling more relatively small planets to be detected, researchers have said.

Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.