Fast-Spinning Star Boasts Never-Before-Seen 'Starspots'

Observations of an unusual fast-spinning star may help explain why such stars, known as pulsars, fluctuate in brightness.

The whirling star is a millisecond pulsar (MSP) that's called J1723-2837. A "millisecond" pulsar is one that rotates all the way around its axis in only a few milliseconds. The star is part of a binary system that includes "one of the fastest-spinning pulsars in our galaxy and its unique companion star," according to a statement on the discovery from the University of Toronto.

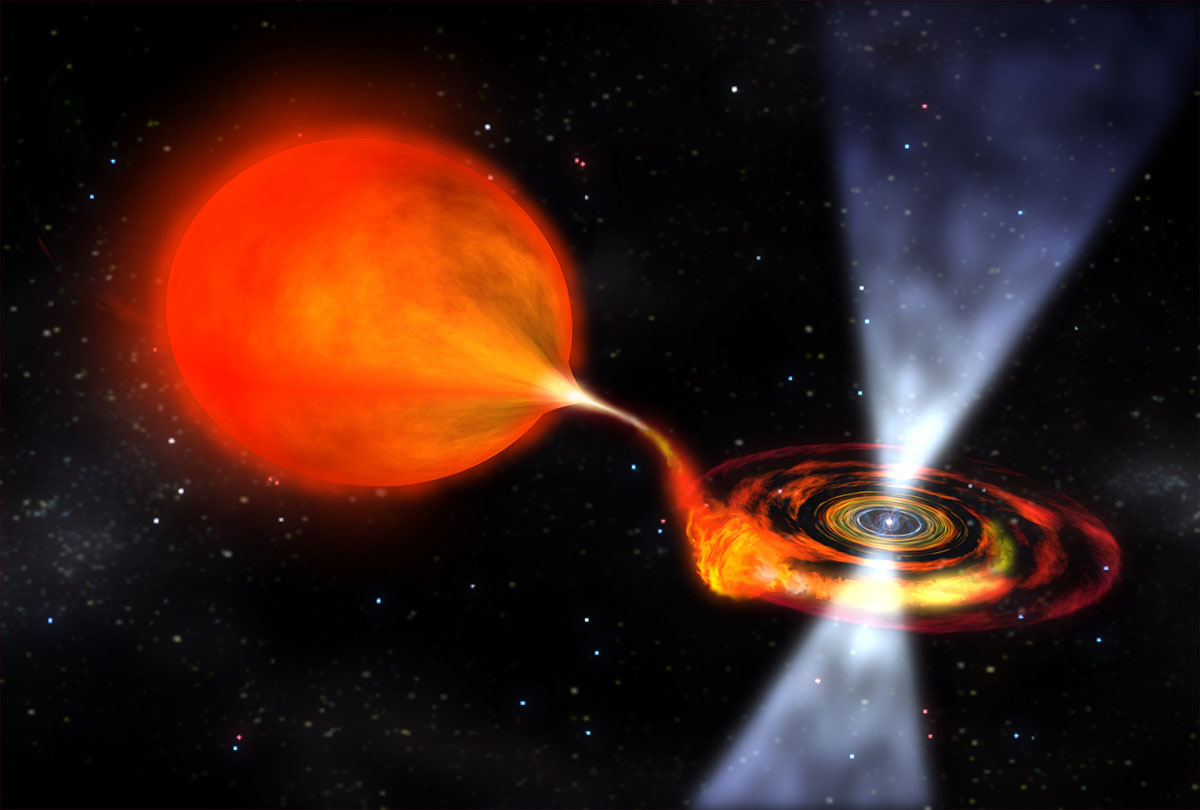

A pulsar can pull in a steady stream of material from its orbiting companion star. During this feeding frenzy, the pulsar gains momentum and begins to spin faster, and, as a result, emits beams of intense radiation. [The Top 10 Strangest Things in Space]

Observations of the system — led by André van Staden, an amateur astronomer from Africa, and astrophysicist John Antoniadis, of the Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics at the University of Toronto — revealed never-before-seen dark patches as well as a strong magnetic field around the pulsar's companion star. Their findings may help explain the unusual rise and fall in the star's brightness.

Typically, when a pulsar is feeding off a companion star, the star is stretched into a teardrop shape as the pulsar syphons material away. When viewed from Earth, this can cause the star to appear to vary in brightness throughout its orbit. When the teardrop profile is facing Earth, the star appears brightest; when it is positioned such that an observer only sees a circular profile, the star appears dimmer. (This only works if observers can see the system along the plane of the star's orbit.) For this reason, the changing brightness of the star should vary in sync with its orbit around the pulsar. But that's not what the new research shows.

"Antoniadis and van Staden's observations revealed that the brightness of the companion (star) wasn't in sync with its 15-hour orbital period; instead the star's peaks in brightness occur progressively later relative to the companion's orbital position," university representatives explained in the same statement.

The researchers determined that the observed lag was likely due to "starspots," which they explained are similar to sunspots, or dark patches on the surface of the sun, that serve to lower the brightness of the star. The existence of those starspots allowed Antoniadis and van Staden to conclude that the companion star has a strong magnetic field, as these spots generally occur in regions of intense magnetic activity.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, "starspots" aren't the only thing that might be interfering with the star's brightness — the researchers also found that the companion star is not tidally locked to the pulsar, and, as a result, "the companion's rotational period is slightly shorter than its orbital period," according to the study, which was published Dec. 7 in the Astrophysical Journal. This means that the position of the starspots would change over multiple orbits, potentially contributing to the irregular brightness changes.

The companion star's magnetic field might be responsible for more than just its starspots, the new work suggests. Some pulsars that feed off a companion star have been found to switch on and off — meaning that their beams of intense radiation fade out and then reappear later. One theory for why this happens holds that waves of intense radiation and stellar wind from the pulsar may suppress the supply of food coming from the companion. But the researchers found no evidence of this phenomenon in their observations. That finding led the researchers to conclude that the companion star's magnetic field could be what periodically cuts off the pulsar's food supply.

"Observations such as van Staden's are critical in answering questions about the evolution and complex relationship between the MSP and its companion in 'black widow' and 'redback' binaries — pairs of stars in which the pulsar, like its arachnid namesake, devours its companion," University of Toronto officials said in the statement.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom,Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.