Saturn's icy moon Enceladus is looking more and more like a habitable world.

The same sorts of chemical reactions that sustain life near deep-sea hydrothermal vents here on Earth could potentially be occurring within Enceladus' subsurface ocean, a new study published today (April 13) in the journal Science suggests.

These reactions depend on the presence of molecular hydrogen (H2), which, the new study reports, is likely being produced continuously by reactions between hot water and rock deep down in Enceladus' sea. [Photos of Enceladus, Saturn's Geyser-Blasting Moon]

"The abundance of H2, along with previously observed carbonate species, suggests a state of chemical disequilibria in the Enceladus ocean that represents a chemical energy source capable of supporting life," Jeffrey Seewald, of the Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry Department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, wrote in an accompanying "Perspectives" piece in the same issue of Science. (Seewald was not involved in the new Enceladus study.)

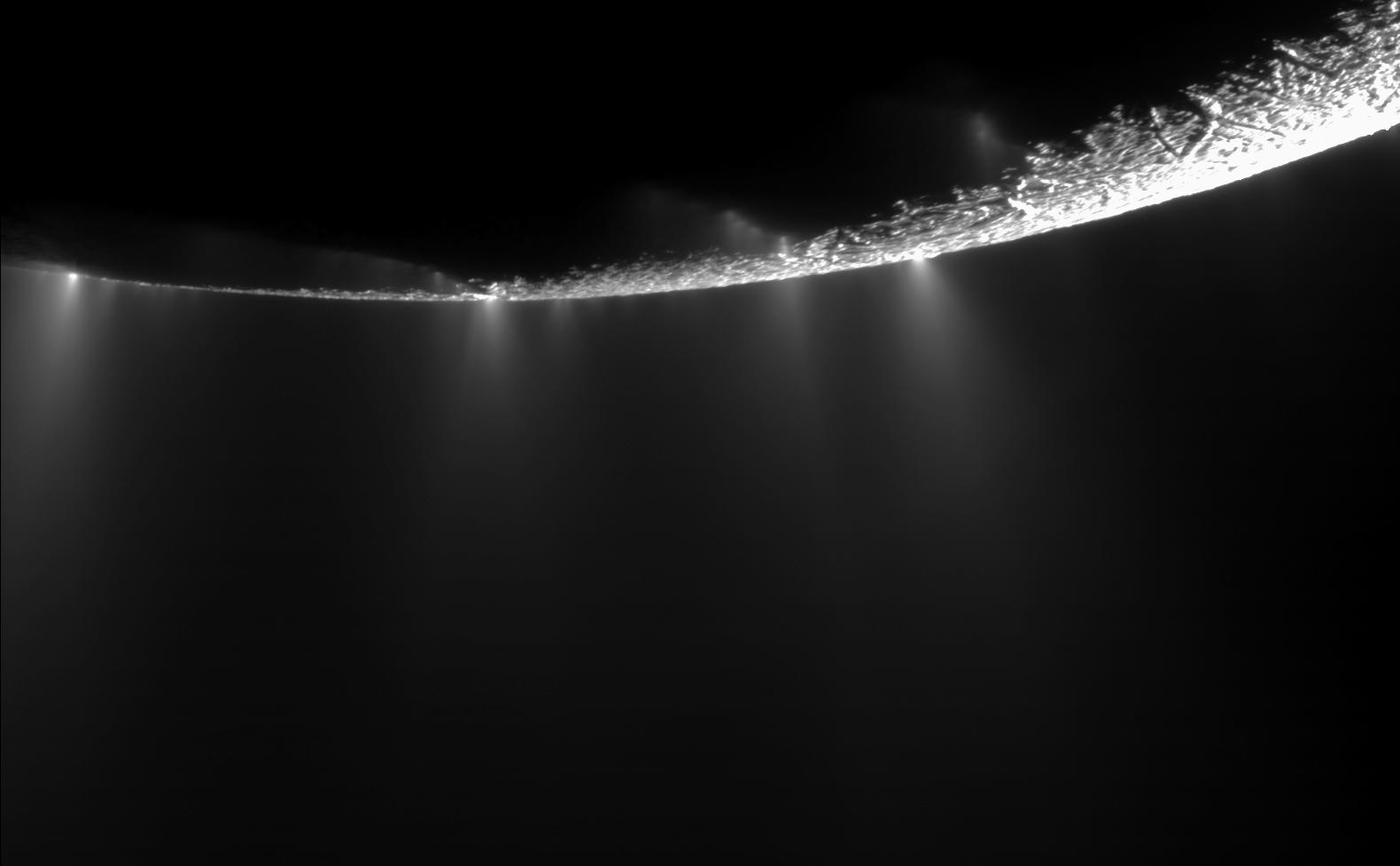

A geyser-blasting ocean world

The 313-mile-wide (504 kilometers) Enceladus is just Saturn's sixth-largest moon, but the object has loomed large in the minds of astrobiologists since 2005.

In that year, NASA's Saturn-orbiting Cassini spacecraft first spotted geysers of water ice erupting from "tiger stripe" fissures near Enceladus' south pole. Scientists think these geysers are blasting material from a sizeable ocean buried beneath the satellite's ice shell.

So, Enceladus has liquid water, one of the key ingredients required for life as we know it. (This ocean stays liquid because Saturn's immense gravitational pull twists and stretches the moon, generating internal "tidal" heat.) And the new study suggests that the satellite possesses another key ingredient as well: an energy source.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A team of researchers led by Hunter Waite, of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in San Antonio, analyzed observations made by Cassini during an October 2015 dive through Enceladus' geyser plume.

This plunge was special in several ways. For one thing, it was Cassini's deepest-ever dive through the plume; the probe got within a mere 30 miles (49 km) of Enceladus' surface. In addition, Cassini's Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) instrument alternated between "open-source" and "closed-source" modes during the encounter, rather than sticking to closed source (the usual routine).

INMS is just 0.25 percent as sensitive in open-source mode as it is in closed-source mode, Waite and his colleagues wrote in the new Science paper. But open source has a key advantage: It minimizes artifacts that have complicated previous attempts to measure H2 levels in the plume.

With this analytical hurdle cleared, Waite and his team were able to calculate that H2 makes up between 0.4 percent and 1.4 percent of the volume of Enceladus' geyser plume. Further calculations revealed that carbon dioxide (CO2) makes up an additional 0.3 percent to 0.8 percent of the plume's volume. [Inside Enceladus, Icy Moon of Saturn (Infographic)]

The molecular hydrogen is most likely being produced continuously by reactions between hot water and rock in and around Enceladus' core, Waite and his colleagues concluded. They considered other possible explanations and found them wanting. For example, neither Enceladus' ocean nor its ice shell are viable long-term reservoirs for volatile H2, the authors wrote, and processes that disassociate H2 from water ice in the shell don't seem capable of generating the volume measured in the plume.

The hydrothermal explanation is also consistent with a 2016 study by another research group, which concluded that tiny silica grains detected by Cassini could have been produced only in hot water at significant depths.

"The story seems to be fitting together," Chris Glein of SwRI, a co-author of the new Science paper, told Space.com.

Deep-sea chemical reactions

Earth's deep-sea hydrothermal vents support rich communities of life, ecosystems powered by chemical energy rather than sunlight.

"Some of the most primitive metabolic pathways utilized by microbes in these environments involve the reduction of carbon dioxide (CO2) with H2 to form methane (CH4) by a process known as methanogenesis," Seewald wrote.

The inferred presence of H2 and CO2 in Enceladus' ocean therefore suggests that similar reactions could well be occurring deep beneath the moon's icy shell. Indeed, the observed H2 levels indicate that a lot of chemical energy is potentially available in the ocean, Glein said.

"It's quite a bit larger than the minimum energy required to support methanogenesis," he said.

Glein stressed, however, that nobody knows whether such reactions are actually occurring on Enceladus.

"This is not a detection of life," Glein said. "It increases the habitability, but I would never suggest that this makes Enceladus more or less likely to have life itself. I think the only way to answer that question is, we need data."

Seewald also counseled caution on astrobiological interpretations. He noted, for example, that molecular hydrogen is rare in Earth's seawater, because hungry microbes quickly gobble it up.

"Is the presence of H2 in the Enceladus ocean an indicator for the absence of life, or is it a reflection of the very different geochemical environment and associated ecosystems on Enceladus?" Seewald wrote. "We still have a long way to go in our understanding of processes regulating the exchange of mass and heat across geological interfaces that define the internal structure of Enceladus and other ice-covered planetary bodies."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.