Newfound Alien Planet Is Best Place Yet to Search for Life

A newly discovered planet around a distant star may jump to the top of the list of places where scientists should go looking for alien life.

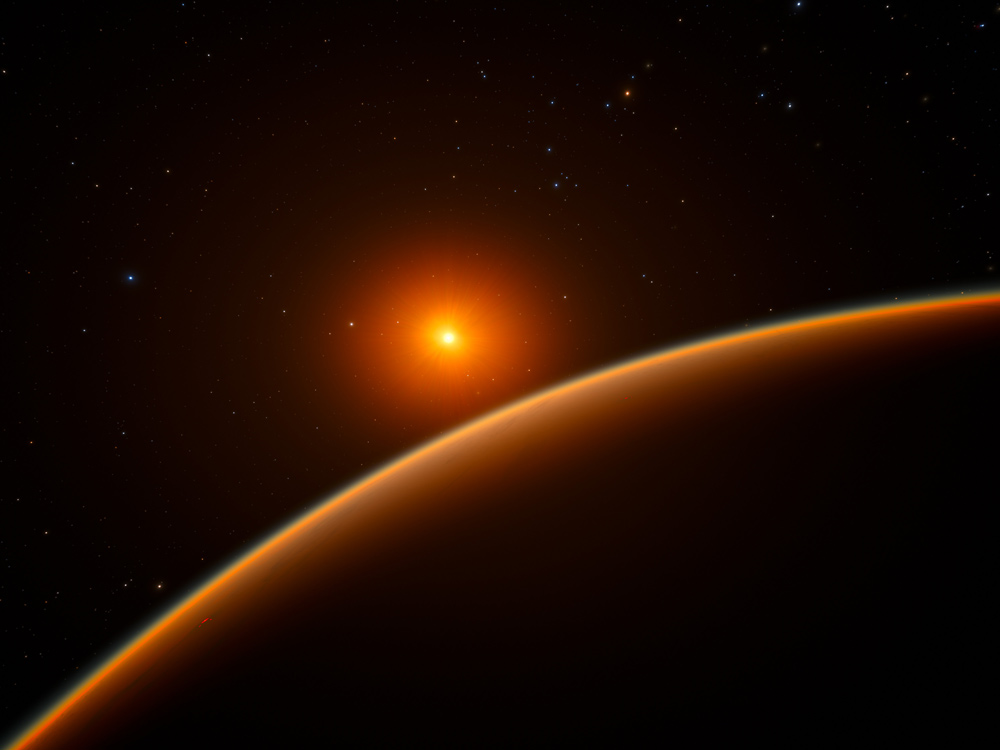

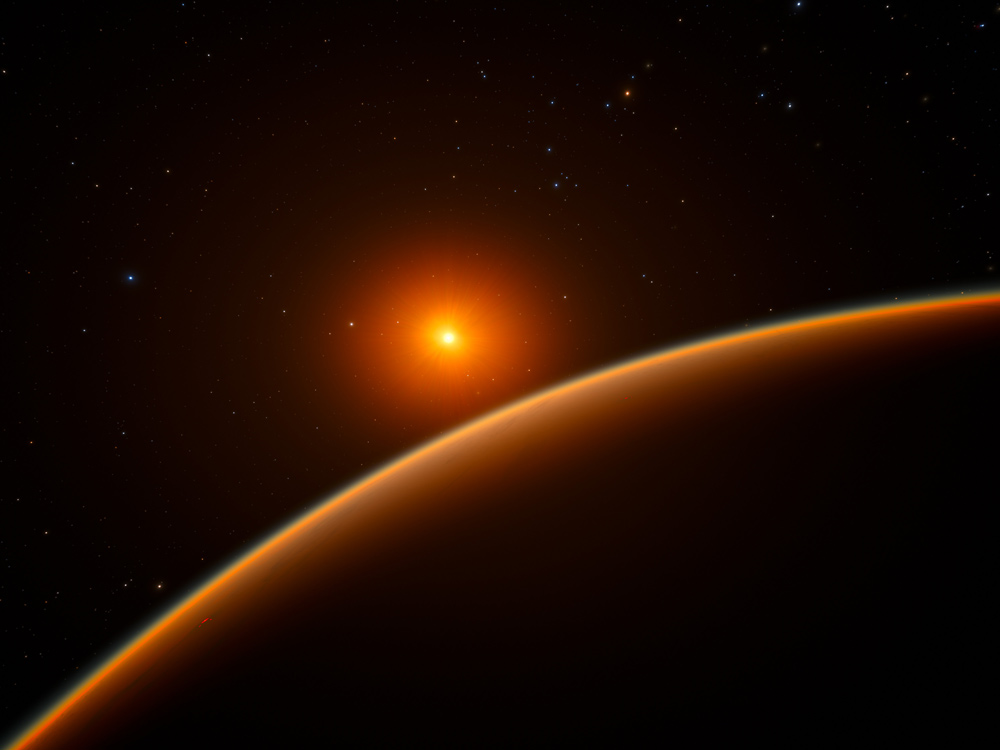

The alien world known as LHS 1140b is rocky, like Earth. It is only 40 light-years away from our solar system (essentially, down-the-street in cosmic terms), and sits in the so-called habitable zone of its parent star, which means liquid water could potentially exist on the planet's surface. Several other planets also meet those criteria, but few of them are as prime for study as LHC 1140b according to the scientists who discovered it, because the type of star the planet orbits and the planet's orientation to Earth make it ripe for investigations into whether it’s the kind of place where life could thrive.

"This is the most exciting exoplanet I've seen in the past decade," Jason Dittmann, a postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and lead author on the paper describing the discovery, said in a statement from CfA. "We could hardly hope for a better target to perform one of the biggest quests in science — searching for evidence of life beyond Earth." [10 Exoplanets That Might Be Perfect to Support Life]

Alien atmosphere

Thousands of exoplanets have been discovered orbiting stars other than the sun in the last 20 years. Many of those planets meet some of the basic requirements for hosting life as we know it — they're rocky like Earth (rather than gaseous, like Saturn or Jupiter) and they sit in the habitable zone of their parent star.

LHS 1140b meets those initial requirements. Through multiple observations, Dittmann and colleagues determined that the planet receives about 0.46 times as much light from its parent star as Earth receives from the sun. The planet is about 1.4 times the diameter of Earth and 6.6 times its mass, which makes it a so-called super-Earth and suggests it is also rocky. [How Habitable Zones for Alien Planets and Stars Work (Infographic)]

The next step scientists are taking to find out if exoplanets like LHS 1140b are habitable (or even inhabited) is to examine their atmospheres. An atmosphere could provide life-forms with a necessary ingredient for life (such as oxygen or carbon dioxide on Earth), and could also bear signs that life exists there (most of the methane on Earth, for example, is produced by biological organisms). Scientists are working on understanding what the atmosphere of an exoplanet can reveal about the likelihood that it hosts life, or could.

Dittmann said he and his colleagues think LHS 1140b is a great candidate for follow-up atmospheric studies for multiple reasons.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This alien world was initially discovered using the transit method, in which scientists look at the light from a star and try to measure subtle dips in its brightness that could be caused by a planet passing in front of (transiting) the star. In some cases, telescopes can capture the sliver of sunlight that passes through the planet's atmosphere, and that sunlight reveals information about the chemical composition of the planet's atmosphere. Many other potentially habitable Earth-like planets ― such as Proxima b, the closest exoplanet to our solar system that lies only 4.2 light-years away ― do not transit their parent star as seen from Earth and therefore their atmospheres can't be studied in this way.

The team's precise measurement of LHS 1140b's density will also be important to understanding its atmosphere, Dittmann told Space.com.

"What's great about having a density ahead of an atmospheric study is that this density tells you how tightly the planet holds on to its atmosphere (the atmospheric scale height)," Dittmann told Space.com in an email. Using the transit method, scientists are trying to collect starlight shining through a planet's atmosphere; a thicker atmosphere means more light passes through it, making it easier for scientists to detect the signals from various chemical elements present in that atmosphere. A planet with higher density also has stronger gravity, which further compresses the atmosphere and reduces the size of the signals scientists can detect.

But clouds can also reduce the size of the signal by simply blocking the light coming through the atmosphere, Dittmann said.

"Since these two things have similar effects, you can't disentangle the two," he said. "Here, having a mass measurement is super helpful because then you already know the effect of the mass of the planet, and anything 'extra' can be due to clouds."

Dittmann and colleagues made that precise density measurement of LHS 1140b through a different method known as the radial velocity technique, in which scientists look for the way an exoplanet tugs on its parent star. Precise measurements of the mass and density of an exoplanets are also not entirely rare, but can be difficult to determine in some systems, as is the case for the recently discovered crop of seven exoplanets orbiting a single star in the TRAPPIST-1 system, which is about 39 light-years from Earth.

"Only one of those worlds has had its density measured accurately, showing that it isn’t rocky," according to the statement from CfA. "Therefore, some or all of the others also might not be rocky."

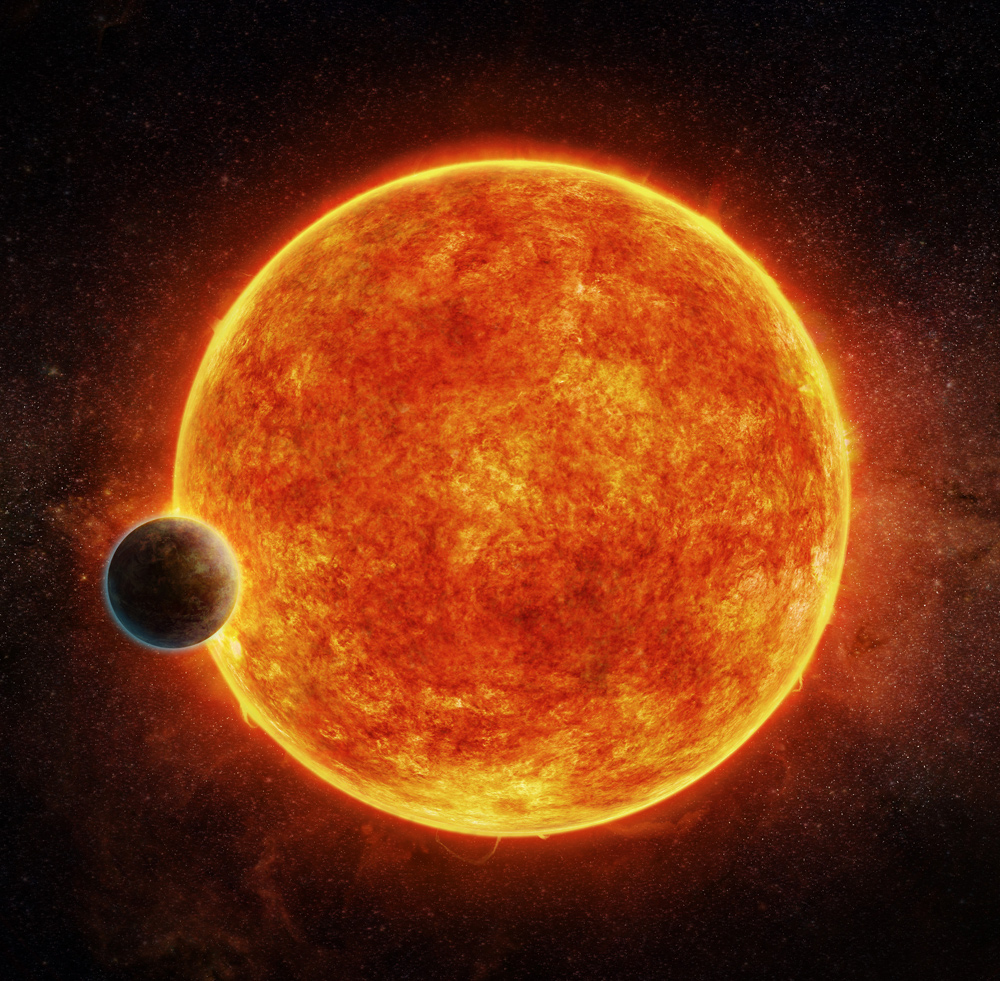

A cool star

Another reason Dittmann and his colleagues think LHS 1140b is a good follow-up in the search for life is because of the kind of star it orbits, even though that star is very different from the sun.

The star LHS 1140 is an M dwarf star (also known as a red dwarf). It is only one-fifth the size of Earth's sun and significantly cooler. But it's extremely difficult to study exoplanets that orbit close to a bright star, because the light from the star drowns out the light from the planet. Around a cooler, dimmer star, that problem is slightly alleviated. In addition, M dwarfs are the most common type of star in the galaxy, which has led some scientists to push for planet searches that target red dwarf stars.

But these dim red stars can also be violent in their early lives, pelting infant planets with harsh ultraviolet radiation and X-rays, potentially evaporating liquid water or snuffing out early forms of life. The star LHS 1140 is a relatively quiet red dwarf, according to the new paper. By comparison, the star at the center of the TRAPPIST-1 system produces more frequent bursts of harsh radiation and has been found to radiate strongly in X-ray wavelengths, Dittmann said. For a planet to sit in the habitable zone around a dim red star, it must orbit much closer to the star than Earth orbits the sun, which can make planets even more susceptible to the harsh effects of the star's radiation.

Dittmann said the team has been approved to use the Hubble Space Telescope to get a better look at the star and see how bright it is in those ultraviolet and X-ray wavelengths. ("We expect it to be very dim, but it's always good to check!" he said.)

The team also plans to use Hubble to start gathering data about LHS 1140b's atmosphere, in anticipation of being able to study it with larger telescopes, such as the James Webb Space Telescope, set to launch in 2018, and the Giant Magellan Telescope and the Thirty Meter Telescope, set to come online in the 2020s.

Scientists may very well not find life on LHS 1140b, but this perfect storm of characteristics makes it the perfect subject to teach scientists about how planets around M dwarfs evolve.

"M dwarfs are the most common type of star in the galaxy, and the discovery of LHS 1140b provides us with an excellent opportunity to learn more about whether planets orbiting these stars are habitable," said Victoria Meadows, a professor of astronomy at the University of Washington, who was not involved in the research. "If planets like LHS 1140b orbiting M dwarfs can be habitable, then it will increase the potential prevalence of life throughout the galaxy."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter