Our Discovery of a Minor Planet Beyond Neptune Shows There May Not Be 'Planet Nine' After All

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Ever since enthusiasm started growing over the possibility that there could be a ninth major planet orbiting the sun beyond Neptune, astronomers have been busy hunting it. One group is investigating four new moving objects found by members of the public to see if they are potential new solar system discoveries. As exciting as this is, researchers are also making discoveries that question the entire prospect of a ninth planet.

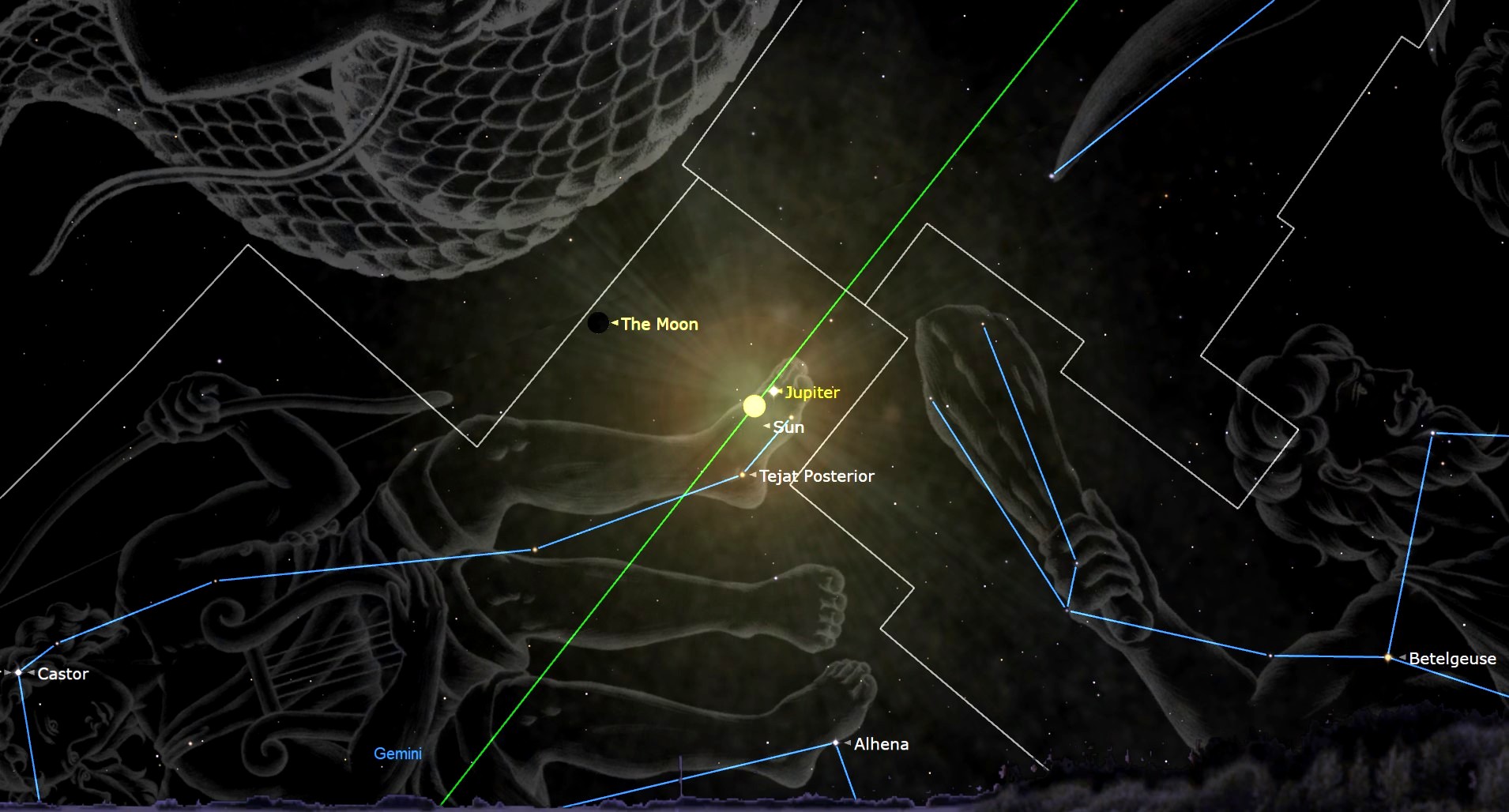

One such finding is our discovery of a minor planet in the outer solar system: 2013 SY99. This small, icy world has an orbit so distant that it takes 20,000 years for one long, looping passage. We found SY99 with the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope as part of the Outer Solar System Origins Survey. SY99's great distance means it travels very slowly across the sky. Our measurements of its motion show that its orbit is a very stretched ellipse, with the closest approach to the sun at 50 times that between the Earth and the sun (a distance of 50 "astronomical units").

The new minor planet loops even further out than previously discovered dwarf planets such as Sedna and 2013 VP113. The long axis of its orbital ellipse is 730 astronomical units. Our observations with other telescopes show that SY99 is a small, reddish world, some 250 kilometres in diameter, or about the size of Wales in the UK.

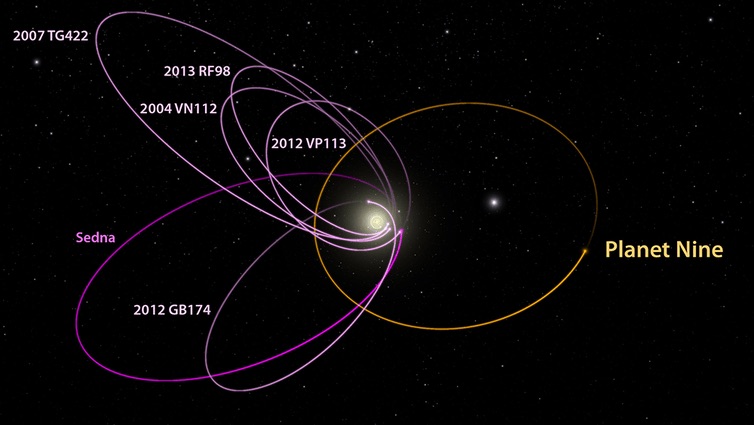

SY99 is one of only seven known small icy worlds that orbit beyond Neptune at remarkable distances. How these "extreme trans-Neptunian objects" were placed on their orbits is uncertain: their distant paths are isolated in space. Their closest approach to the sun is so far beyond Neptune that they are thought to be "detached" from the strong gravitational influence of the giant planets in our solar system. But at their furthest points, they are still too close to be nudged around by the slow tides of the galaxy itself.

It's been suggested that the extreme trans-Neptunian objects could be clustered in space by the gravitational influence of a "Planet Nine" that orbits much further out than Neptune. This planet's gravity could lift out and detach their orbits – constantly changing their tilt. But this planet is far from proven.

In fact, its existence is based on the orbits of only six objects, which are very faint and hard to discover even with large telescopes. They are therefore prone to odd biases. It's a bit like looking down into the deep ocean at a school of fish. The fish swimming near the surface are clearly visible. But the ones even only a meter down are fainter and murky, and take quite a lot of peering to be certain. The great bulk of the school, in the depths, is completely invisible. But the fish at the surface and their behaviour betray the existence of a whole school.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The biases mean SY99's discovery can't prove or disprove the existence of a Planet Nine. However, computer models do show that a Planet Nine would be an unfriendly neighbour to tiny worlds like SY99: its gravitational influence would starkly change its orbit – throwing it from the solar system entirely, or poking it into an orbit so highly inclined and distant that we wouldn't be able to see it. SY99 would have to be one of an utterly vast throng of small worlds, continuously being sucked in and cast out by the planet.

The alternative explanation

But it turns out that there are other explanations. Our study based on computer modelling, accepted for publication in the Astronomical Journal, hint at the influence of an idea from everyday physics called diffusion. This is a very common type of behaviour in the natural world. Diffusion typically explains the random movement of a substance from a region of higher concentration to one of lower concentration – such as the way perfume drifts across a room.

We showed that a related form of diffusion can cause the orbits of minor planets to change from an ellipse that is initially only 730 astronomical units on its long axis to one that is as big as 2,000 astronomical units or bigger – and change it back again. In this process, the size of each orbit would vary by a random amount. When SY99 comes to its closest approach every 20,000 years, Neptune will often be in a different part of its orbit on the opposite side of the solar system. But at encounters where both SY99 and Neptune are close, Neptune's gravity will subtly nudge SY99, minutely changing its velocity. As SY99 travels out away from the sun, the shape of its next orbit will be different.

The long axis of SY99's ellipse will alter, becoming either larger or smaller, in what physicists call a "random walk." The orbit change takes place on truly astronomical time scales. It diffuses over the space of tens of millions of years. The long axis of SY99's ellipse would change by hundreds of astronomical units over the 4.5 billion-year history of the solar system.

Several other extreme trans-Neptunian objects with smaller orbits also show diffusion, on a smaller scale. Where one goes, more can follow. It's entirely plausible that the gradual effects of diffusion act on the tens of millions of tiny worlds orbiting in the near fringe of the Oort cloud (a shell of icy objects at the edge of the solar system). This gentle influence would slowly lead some of them to randomly shift their orbits closer to us, where we see them as extreme trans-Neptunian objects.

However, diffusion won't explain the distant orbit of Sedna, which has its closest point too far out from Neptune for it to change its orbit's shape. Perhaps Sedna gained its orbit from a passing star, aeons ago. But diffusion could certainly be bringing in extreme trans-Neptunian objects from the inner Oort cloud – without the need for a Planet Nine. To find out for sure, we'll need to make more discoveries in this most distant region using our largest telescopes.

Michele Bannister, Research Fellow, planetary astronomy, Queen's University Belfast

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.