Update for Sept. 15: Cassini has made its final plunge into Saturn. See our final farewell here: RIP, Cassini: Historic Mission Ends with Fiery Plunge into Saturn

The final photos taken by NASA's Cassini Saturn orbiter have begun coming down to Earth, and you can see them all.

Cassini is clearing its memory ahead of its dive into Saturn's atmosphere early Friday morning (Sept. 15), a suicide plunge that will bring the storied spacecraft's 20 years in space to a dramatic, fiery end.

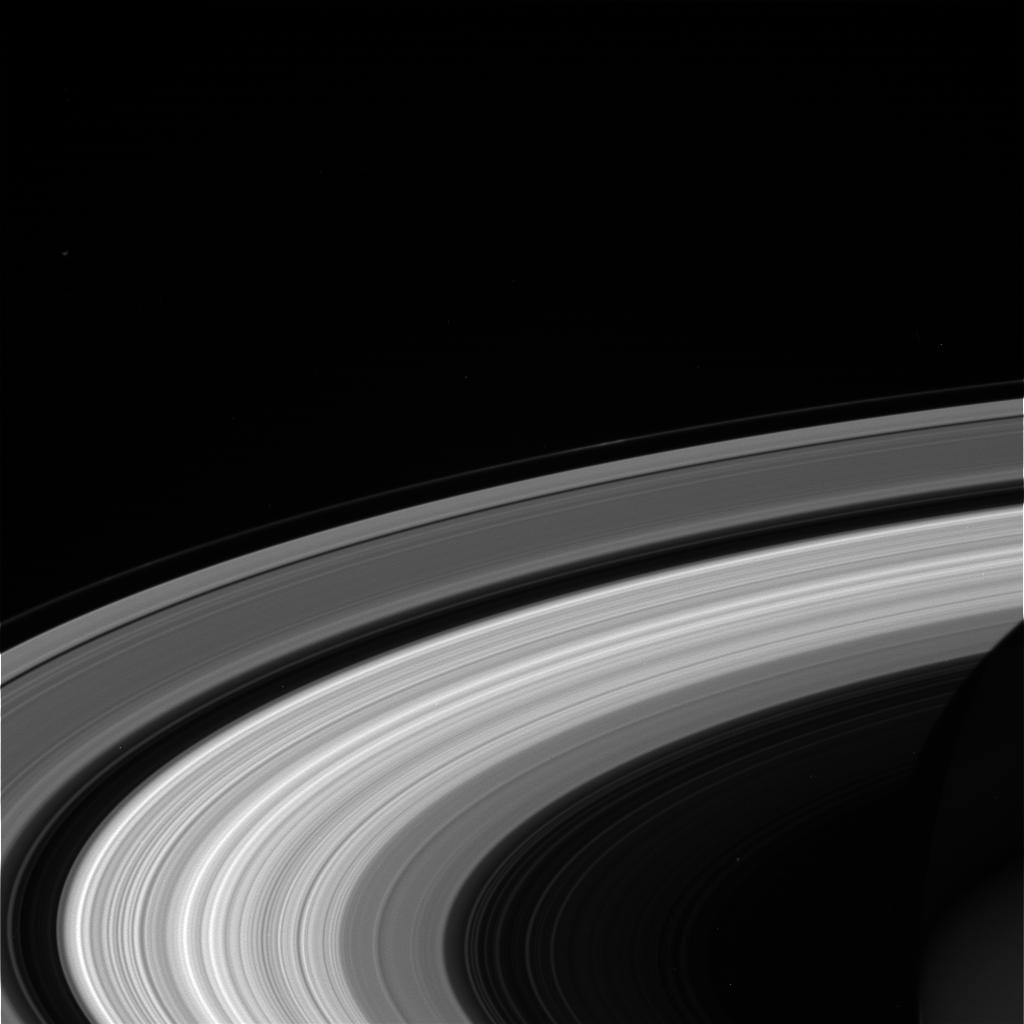

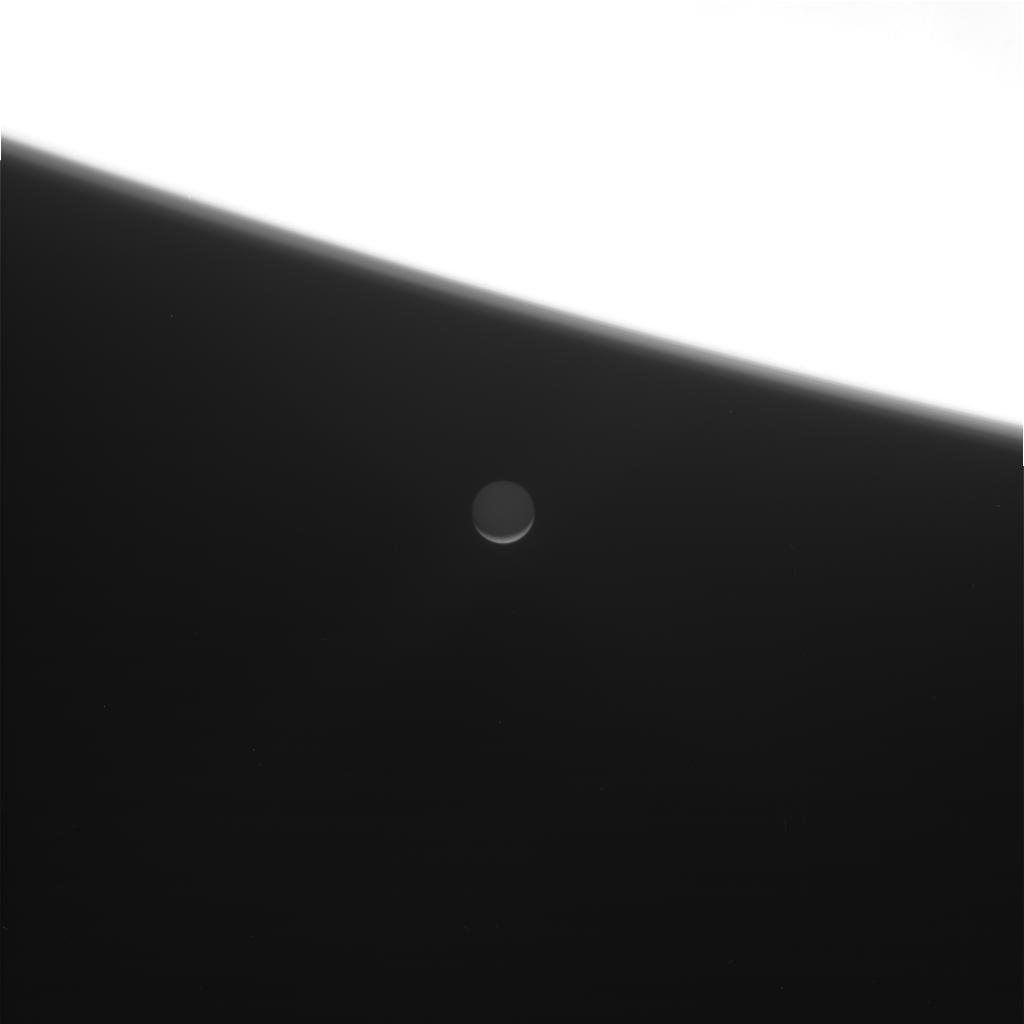

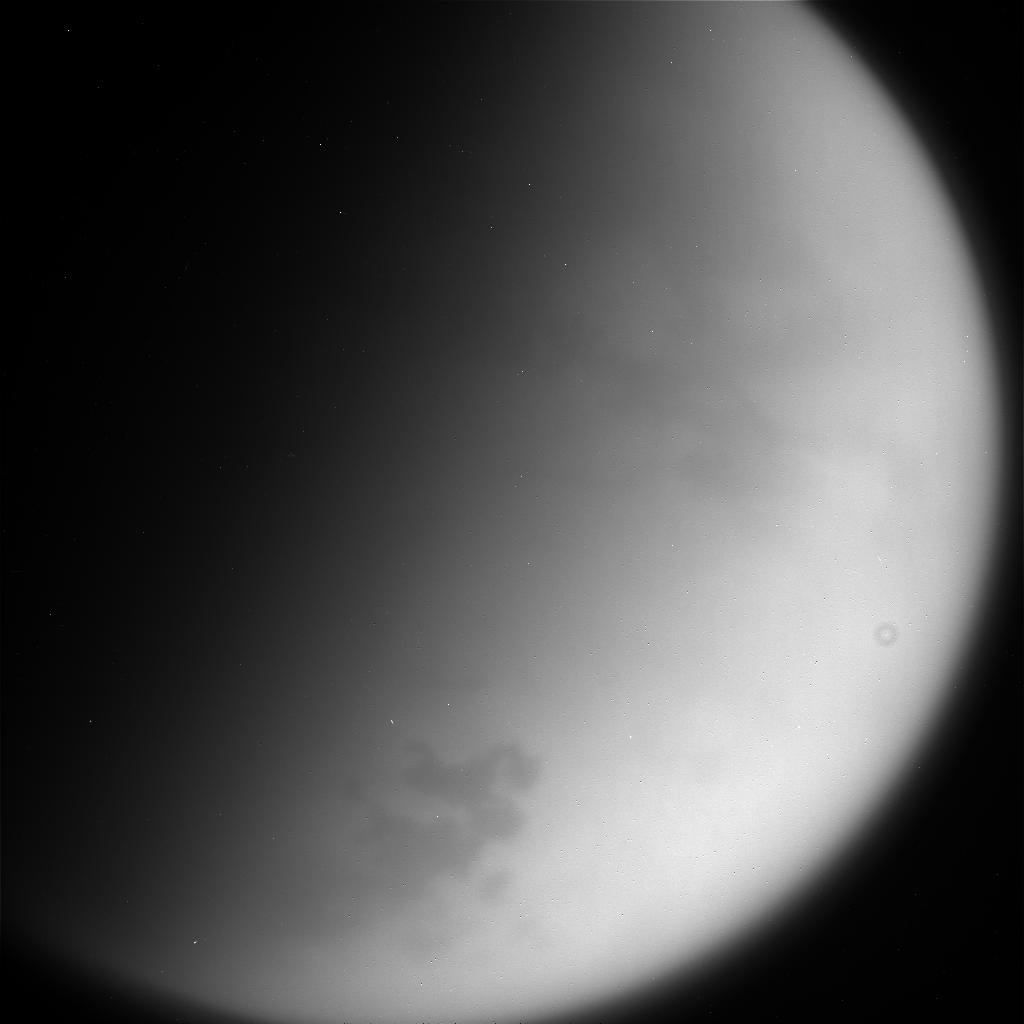

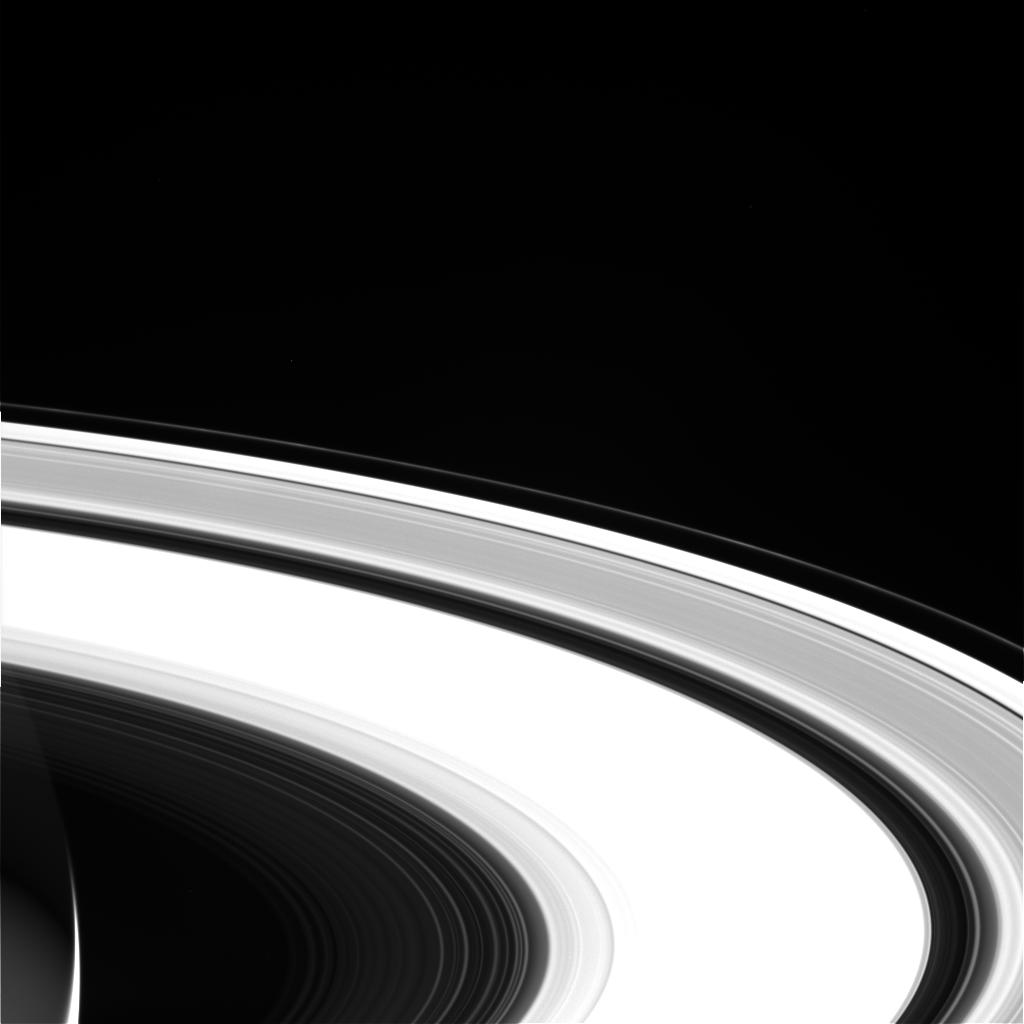

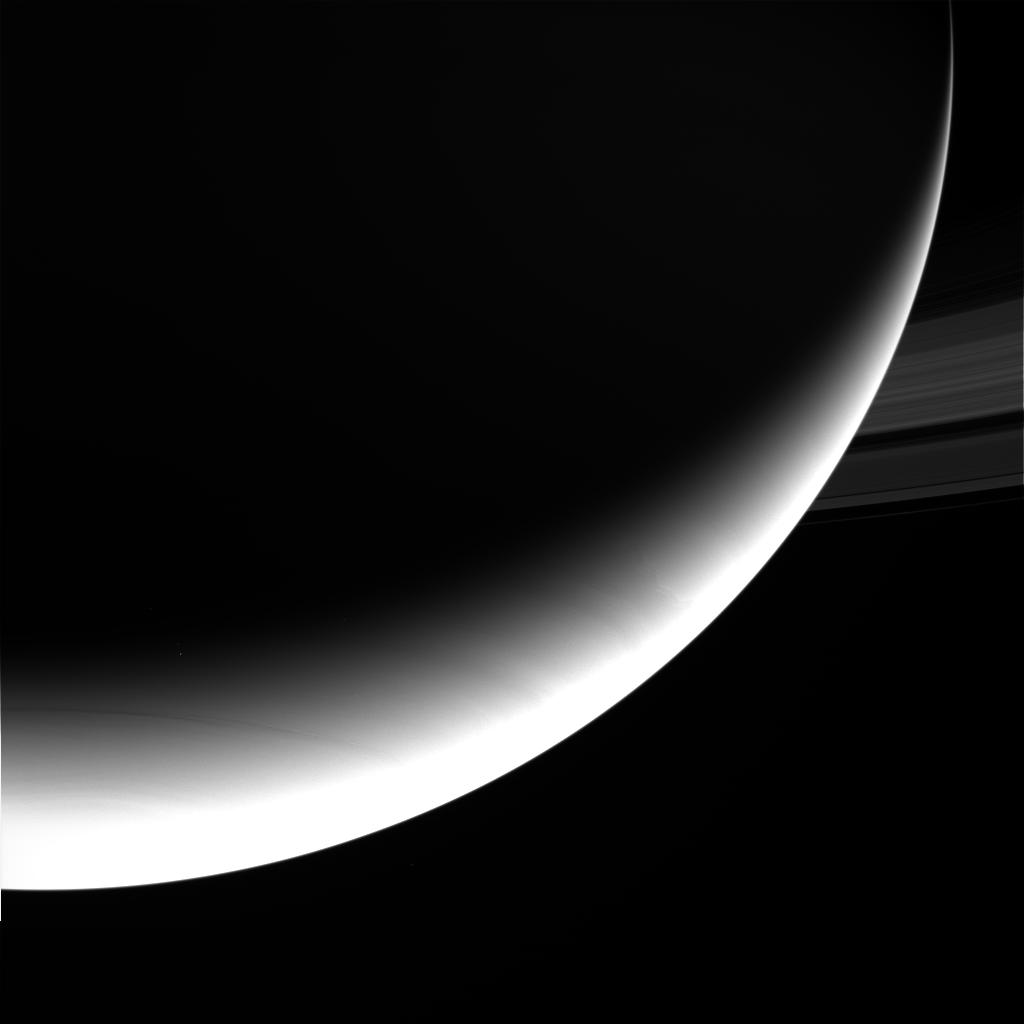

The newly arrived images are a fitting coda for Cassini's mission — diverse and beautiful. They capture, among other things, the potentially habitable Saturn moons Titan and Enceladus, the gas giant's graceful limb and its iconic rings. [In Photos: Cassini's Last Views of Saturn at Mission's End]

We've given you just a small sampling in this story; check out all of them as they come in here: https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/galleries/raw-images/

The $3.2 billion Cassini-Huygens mission — a joint effort of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency — launched in October 1997 and arrived in orbit around Saturn on the night of June 30, 2004.

A lander called Huygens piggybacked aboard the Cassini mothership, eventually touching down on Titan's frigid, otherworldly surface in January 2005. The orbiter, meanwhile, kept cruising through the Saturn system, studying the giant planet, its rings and its diverse panoply of moons.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cassini's discoveries have fundamentally reshaped scientists' understanding of Saturn, and of the solar system's life-hosting potential. For example, the orbiter spotted lakes of liquid hydrocarbons (mostly methane) on Titan's surface, and its observations suggest that the huge moon also hosts an ocean of salty water beneath its crust.

And Cassini spotted geysers of water vapor blasting from the southern reaches of the 313-mile-wide (504 kilometers) moon Enceladus. Further work by Cassini indicated that this water is coming from a buried ocean, which likely contains a source of chemical energy for microbes, if any ever evolved on that distant moon.

But Cassini is running out of fuel, and mission team members want to dispose of the spacecraft responsibly before it escapes their control. They decided to steer it toward a fiery death in Saturn's atmosphere primarily to protect Titan and Enceladus — to ensure that any Earth microbes that may have hitched a ride aboard Cassini never contaminate those two possibly habitable moons.

Cassini took its last photo — a shot of the patch of atmosphere where it will meet its doom — at 12:58 p.m. PDT (3:58 p.m. EDT, 1958 GMT) Thursday (Sept. 14). Nearly two hours later, the probe began relaying all the information on its solid-state recorder to mission control, to prepare for a transition to near-real-time data transmission during its suicide plunge.

That plunge is nearly upon us: The loss of signal indicating Cassini's death is expected at 4:55 a.m. PDT (7:55 a.m. EDT, 1155 GMT) Friday.

If it's any consolation, Cassini's death should be very quick.

During the dive, the orbiter will be going so fast, and Saturn's atmosphere will be thickening from its perspective so quickly, "that Cassini will be vaporized in I think maybe 2 minutes — [actually] I think more like 1," Cassini project manager Earl Maize, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said during a news conference Wednesday (Sept. 13).

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.