How Cassini Managed to Live Such a Long and Useful Life at Saturn

PASADENA, Calif. – The Cassini spacecraft explored the Saturn system for 13 years — eight years longer than it was initially scheduled for. What's the secret to the mission's long life? Cassini team members told Space.com it comes down to having both a dedicated workforce and long-term planning.

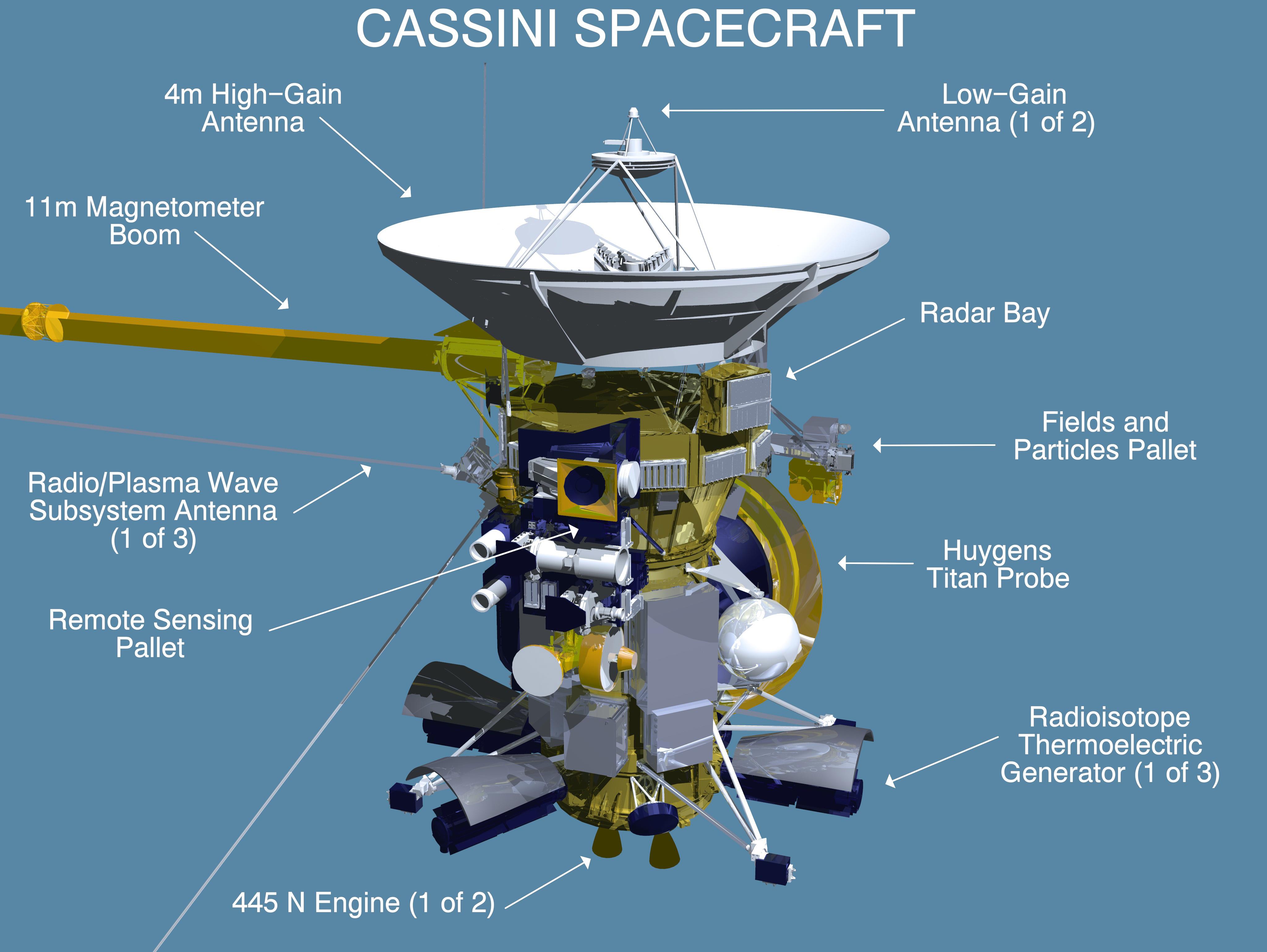

Last week, the Cassini spacecraft met its fiery doom when mission planners sent it plummeting into Saturn's atmosphere. The little probe sent back data about that alien environment for as long as it possibly could — firing its thrusters at full capacity to fight against the drag of the atmosphere and keep its antennae pointed toward Earth.

Mission scientists gathered at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) on Sept. 15 to say goodbye to the probe and watch its final plunge. JPL was the lead institute on designing and building Cassini, and the probe was operated from JPL, using the facility's Deep Space Network. [Farewell, Cassini: Gorgeous Final Photos Are a Fitting Send-Off]

Erick Sturm, the Cassini mission planner, was in JPL's Mission Control Center during Cassini's final hours, watching as data poured in from the probe until the very last second. Over the next few months, he'll work with colleagues to determine just how far into Saturn's atmosphere the probe fell and where it finally disintegrated.

He'll also write a report about the lessons he and his team learned from the Cassini mission that can be applied to future missions. His two main pieces of advice — prepare for surprises, and assume a spacecraft is going to last longer than expected.

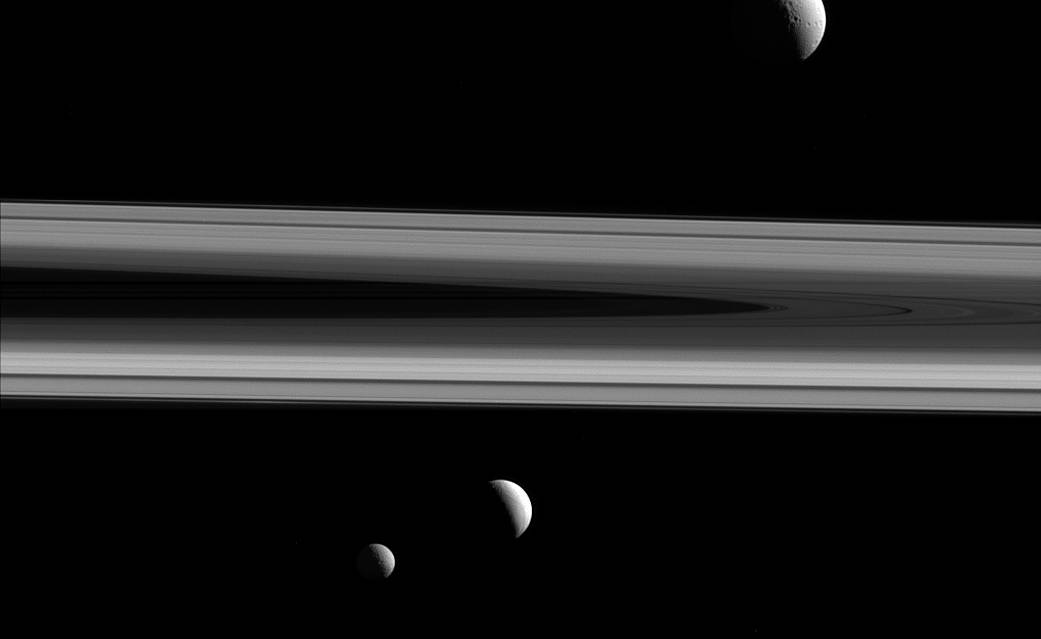

The $3.26 billion Cassini-Huygens mission — a joint effort among NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency — arrived at the Saturn system in 2004. The Huygens lander separated from Cassini and plopped down on the surface of the moon Titan in 2005. Cassini was originally scheduled to explore the Saturn system until 2008 but was given two extensions that kept it operating into 2017. It traveled a total of 4.9 billion miles in its lifetime, and made 162 targeted flybys of Saturn's moons (127 of those were of Titan). The mission came to an end only because the spacecraft was out of fuel.

"We design things so they'll get through their prime mission with a probability [of success] in the high 90 percents, which means you're most likely going to have an [operational] spacecraft at the end of that," Sturm said. "So be ready for what you want to do with [the spacecraft]. Think about how can you best take advantage of it."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kim Steadman, a 14-year veteran of the Cassini mission, agreed that scientists should plan for a long lifetime regarding the spacecraft, but that also means assuming lots of things will break.

As flight systems engineer, Steadman helped the Cassini scientists get the data they wanted out of the mission, by figuring out such things as how to change the spacecraft's flight trajectory and how to make sure the right instruments were able to collect the right data at the right time. (Steadman now works on the Mars 2020 rover).

When asked how it was that Cassini managed to live for so long, Steadman said it came down to redundancy. She listed half a dozen systems or components on Cassini that stopped working during its lifetime, including some of the probe's thrusters and a reaction wheel, both of which are necessary to steer the spacecraft. Without those components, the mission wouldn't have been able to point its instruments in the right direction to collect data, or point its antennae back at Earth to return the data. Cassini, however, was built with backups for all those critical components.

Gas in the tank

Todd Barber, Cassini's lead propulsion engineer, told Space.com that there was one more component he wished the Cassini team had added: a gas gauge.

Barber served as Cassini's "human gas gauge" for many years, he said, meaning it was his job to calculate (through various indirect means) how much fuel was left on the spacecraft. While the probe was equipped with more than enough fuel to complete its primary mission, the two extended missions drove the fuel down to nearly zero.

By the time the probe crashed into Saturn, it had about 1 percent of its fuel left. But Barber said there was enough of an error on that measurement that the team members were constantly nervous about the probe not being able to make all of its final maneuvers.

Fuel gauges used on Earth work in the presence of Earth's gravity (the liquid fuel must sit at the bottom of a container), so on spacecraft (which operate in microgravity), engineers had to come up with another system.

"On a future mission — so that I don't have to lose so much sleep — I'd love to have a flow meter or some kind of way to get an accurate gauge of how much propellant we use," Barber said.

The human element

Researchers are eager to dig through the information the probe sent back during its final descent. (It was the first spacecraft to ever sample Saturn's atmosphere "in situ."). Over the course of its lifetime, the probe sent back so much data that there have already been 3,984 scientific papers published using Cassini data, according to NASA.

Steadman said part of the reason the extended mission was so successful was that the Cassini team was able to adapt to new challenges that arose. One challenge included making closer flybys of Enceladus to examine the geysers erupting from its surface. Another involved making additional flybys of Titan to not only study that moon's bizarre landscape in more detail, but to also use the gravity of Titan to change Cassini's course and fly around the planet at different orbits using less fuel.

Every time the Cassini probe made a flyby of one of Saturn's moons, or when the scientists wanted to look at a specific part of the planet at a specific time, the engineering team would have to schedule and execute maneuvers that would put the spacecraft in the right place at the right time, and pointed in the right direction, Steadman said.

"The team that has operated Cassini is just so dedicated," Steadman said. "We put a lot of hours in to make sure [the spacecraft would] do what we want her to do and not get injured. It's a lot of hard work."

Steadman said one of the things that motivated her to work so hard was learning about the science that the spacecraft was uncovering. She said Linda Spilker, the Cassini project scientist, would do "in-reach" (as opposed to "outreach") and talk to the mission engineers about the science results from the mission.

"Those [maneuvers] were a lot of middle-of-the-night hours, weekend hours, holiday hours," she said. "We commanded the spacecraft on Christmas day once because we had an issue. You're getting phone calls in the middle of the night, getting woken up to come in and tend to your spacecraft. And to have the energy to do that and to really care, you need to see the science that's coming back."

Barber, who has worked on Cassini for just over 20 years, said the science return is also what kept him motivated.

"I'm here because I'm an absolute planetary science junkie and geek. As a kid, that was what drove me," he said. "[Being] a propulsion engineer is how I get to work here, but in my heart I'm a planetary scientist. So that meant so much to me personally, to get to follow the science and do every last thing I could in the mission to make the science successful."

The Cassini mission scientists have funding for another year to study the data the spacecraft sent back to Earth in its final weeks and, especially, those final minutes when it dove into Saturn's atmosphere, Spilker said during a news conference in August.

But for many of the mission team members, their work with Cassini is done. They've already found work on other projects. Some of the team members will spend the next few months compiling various final reports, before they find other assignments as well. When they move on, they'll take the lessons they learned from Cassini with them.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter