Euclid 'dark universe' telescope team will unveil new full-color images today (May 23): How to watch live

"Euclid's ability to unravel the secrets of the cosmos is something you will not want to miss."

Editor's note: The new Euclid telescope images were released at 5:00 a.m. EDT (1200 CEST). You can see the five new views of the cosmos here in our image release story.

The European Space Agency (ESA) will release five new images from the Euclid space telescope today (May 23). And, well, if the previous set of pictures is anything to go by — space fans should be in for an absolute treat.

"Five new portraits of our cosmos were captured during Euclid's early observations phase, each revealing amazing new science," ESA officials said in a statement. "Euclid's ability to unravel the secrets of the cosmos is something you will not want to miss."

The new images will be revealed at 5:00 a.m. EDT (1200 CEST) and will be accompanied by an incredible 10 science papers. You can watch the data release live on the ESA's YouTube channel.

Related: Euclid 'dark universe' telescope gets de-iced from a million miles away

As an appetizer for the occasion, perhaps we can remind ourselves of the incredible cosmic images this mission has delivered thus far.

Euclid's story so far

Having launched on July 1, 2023 from Cape Canaveral in Florida atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, Euclid is a wide-angle space telescope carrying a 600-megapixel camera that observes the cosmos in visible light, a near-infrared spectrometer and a photometer that is used to determine the redshift of galaxies. Knowing about redshift allows scientists to figure out how fast distant galaxies are moving away from our planet.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Euclid's primary mission is to investigate the universe's two most mysterious elements: dark energy and dark matter. These phenomena collectively make up what's often called the "dark universe."

Dark energy is the placeholder name given to whatever force is causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate. Dark matter, on the other hand, is a form of matter that is effectively invisible because it doesn't interact with light. This means scientists know it isn't "ordinary" matter made of electrons, protons and neutrons that comprises stars, planets, moons and our bodies. Dark matter can only make its presence known through its interactions with gravity, which can, in turn, influence ordinary matter and light. To be clear, however, neither dark matter nor dark energy are necessarily made of one thing. Both can be made of lots of things — or, maybe they are indeed each made of one homogenous thing.

The point is, we simply don't know.

Nonetheless, dark energy is thought to make up around 68% of the universe's energy and matter budget, while dark matter comprises about 27%. That means the dark universe accounts for 95% of the stuff in the universe and things we actually do understand account for just about 5%.

So, dubbed a "dark-universe detective" due to its specific packet of instruments, Euclid clearly has its work cut out for it. But surely, the first official images from the space telescope released on Nov. 7, 2023, after its first four months in space, showed it is up to the task.

Just above is one of the first images the public saw from the Euclid telescope. It's a snapshot showing 1,000 galaxies or so, all belonging to the Perseus Cluster. Located around 240 million light-years away from Earth, this cluster is one of the largest structures in the known universe.

Mapping galaxies in such huge volumes is key to understanding how dark matter is distributed and how this distribution has influenced the evolution of the universe.

Beyond the wealth of Perseus Cluster galaxies, the image also showcased a further 100,000 much more distant galaxies, each containing up to hundreds of billions of stars. Observations of distant galaxies in large numbers like this are key to Euclid unraveling how dark energy is pushing these galaxies away faster and faster by speeding up the expansion of the space between them.

Just because Euclid has its eyes on vast swathes of galaxies doesn't mean it can't impress with images of single galaxies.

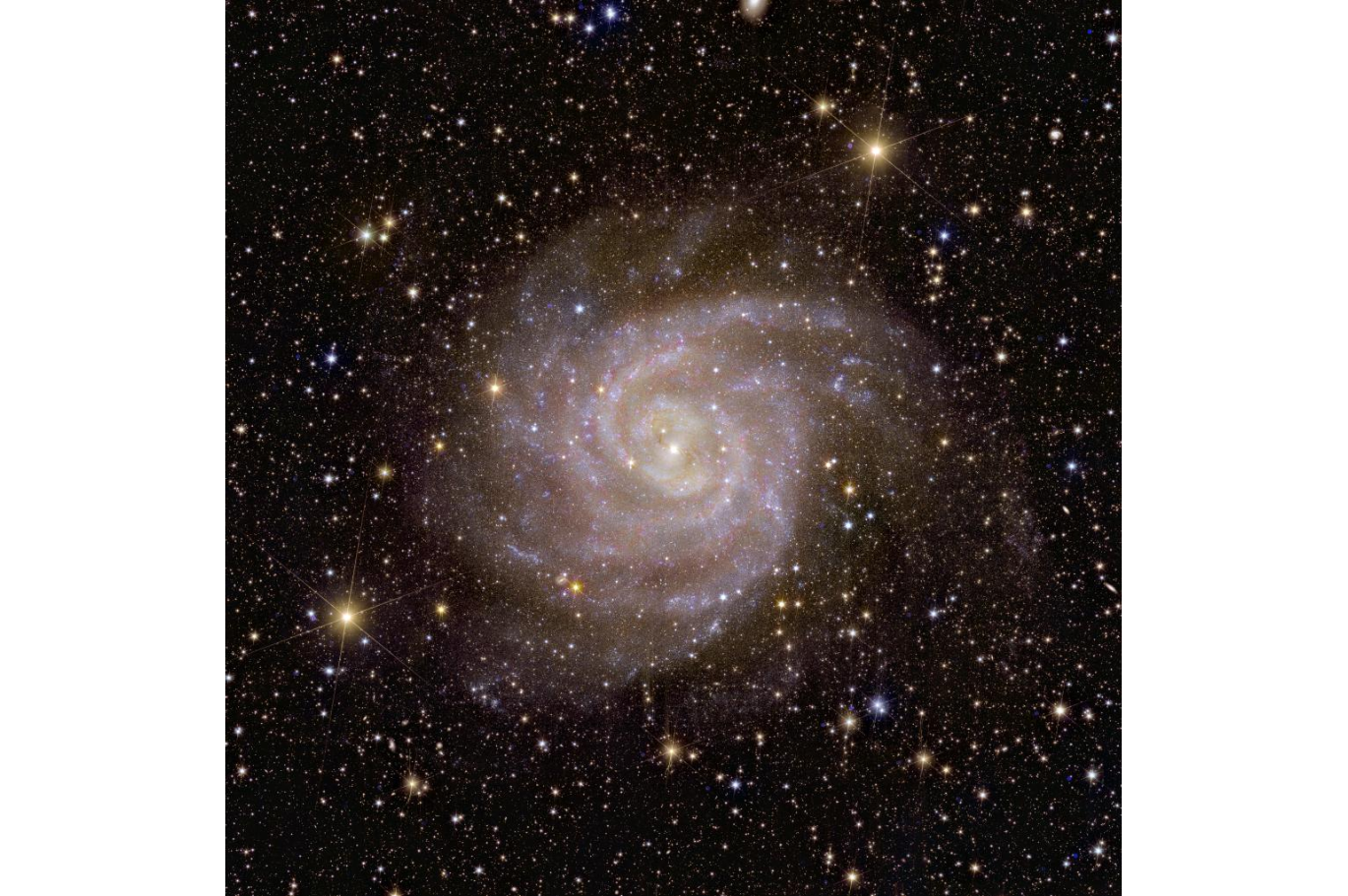

Another of the first Euclid images we got to lay eyes on was somewhat ironically for an instrument tasked with unveiling dark elements of the universe. That's because it identified the galaxy IC 342, also known as the "Hidden Galaxy."

This galaxy is located around 11 million light-years from Earth and is difficult to image because it lies behind the bright, dusty disk of the Milky Way. That didn't stop Euclid from capturing an incredible image of this once-hidden spiral galaxy, however. To do this, the space telescope used its near-infrared instrument, which is advantageous because the gas and dust of the Milky Way's disk are less effective at absorbing infrared light in comparison to other wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation.

To uncover the mysteries of the dark universe and to create a detailed 3D map of the cosmos, Euclid will need to view galaxies as distant as 10 billion light-years away by seeing the 13.8 billion-year-old universe as it was less than 4 billion years after the Big Bang.

These galaxies likely won't possess neat, spiral-like arrangements of the Milky Way or even the Hidden Galaxy. Most galaxies in the early universe are "blobby," poorly shaped irregular galaxies that served as the building blocks for larger galaxies.

To prepare for observing these distant and early galaxies, Euclid's first images included a view of the more local irregular galaxy, NGC 6822, located just 1.6 million light-years from Earth.

Though they offer us spectacularly sparkly images, Euclid won't just focus on galaxies during its mission.

As the image of NGC 6397 above demonstrates, the space telescope will also be watching globular clusters. And, thankfully, globular clusters are just as beautiful. These are conglomerations of hundreds of thousands of stars bound together by gravity, and they are some of the oldest structures in the known universe.

NGC 6397 is the second closest globular cluster to Earth at just around 7,800 light-years away. Globular clusters like NGC 6397 orbit the disk of the Milky Way and can contain clues regarding either the evolution of our galaxy, or at least of other galaxies such structures are found within.

Euclid will excel in the study of globular clusters because, unlike other telescopes, it has a wide enough field of view to catch entire globular clusters in one image just as it did for NGC 6397.

So much of Euclid's mission will focus on the unknown, but the last image from the first batch of Euclid releases actually showed us a familiar celestial object in an entirely new light. The dark universe detective was able to create a stunningly detailed panoramic view of the Horsehead Nebula, also known as Barnard 33.

Located around 1,380 light-years from Earth and situated near the east of Orion's Belt, the Horsehead Nebula is one of the closest star-forming clouds of gas and dust to the solar system. It is also quite a sight to behold.

Though a wealth of telescopes have imaged the Horsehead Nebula in the past, none have captured this region of the Orion molecular cloud with such a wide and sharp view. What is even more staggering about this image is that it took Euclid just an hour of observing time to create it. It's of little wonder that professional and amateur astronomers and space fans alike are excited for the upcoming May 23 data release.

To that end, as breathtaking as the images detailed above are, there is a good chance that the best is yet to come from Euclid as it starts to meet its mission objectives while shedding a curious light on the dark universe.

We'll have to wait until early Thursday to see what the next crop of Euclid images delivers and to see how this dark universe detective is starting to live up to its huge mission expectations after almost a year in space. But, again, if its past is any indication of its future, it's difficult to imagine anything besides information-rich beauty from these images.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.