Astronomers have pinpointed the origin of mysterious repeating radio bursts from space

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights. Natasha Hurley-Walker is a Senior Lecturer and ARC Future Fellow at the Curtin University node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research.

Slowly repeating bursts of intense radio waves from space have puzzled astronomers since they were discovered in 2022.

In new research, we have for the first time tracked one of these pulsating signals back to its source: a common kind of lightweight star called a red dwarf, likely in a binary orbit with a white dwarf, the core of another star that exploded long ago.

A slowly pulsing mystery

In 2022, our team made an amazing discovery: periodic radio pulsations that repeated every 18 minutes, emanating from space. The pulses outshone everything nearby, flashed brilliantly for three months, then disappeared.

We know some repeating radio signals come from a kind of neutron star called a radio pulsar, which spins rapidly (typically once a second or faster), beaming out radio waves like a lighthouse. The trouble is, our current theories say a pulsar spinning only once every 18 minutes should not produce radio waves.

So we thought our 2022 discovery could point to new and exciting physics – or help explain exactly how pulsars emit radiation, which despite 50 years of research is still not understood very well.

More slowly blinking radio sources have been discovered since then. There are now about ten known "long-period radio transients".

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, just finding more hasn't been enough to solve the mystery.

Searching the outskirts of the galaxy

Until now, every one of these sources has been found deep in the heart of the Milky Way.

This makes it very hard to figure out what kind of star or object produces the radio waves, because there are thousands of stars in a small area. Any one of them could be responsible for the signal, or none of them.

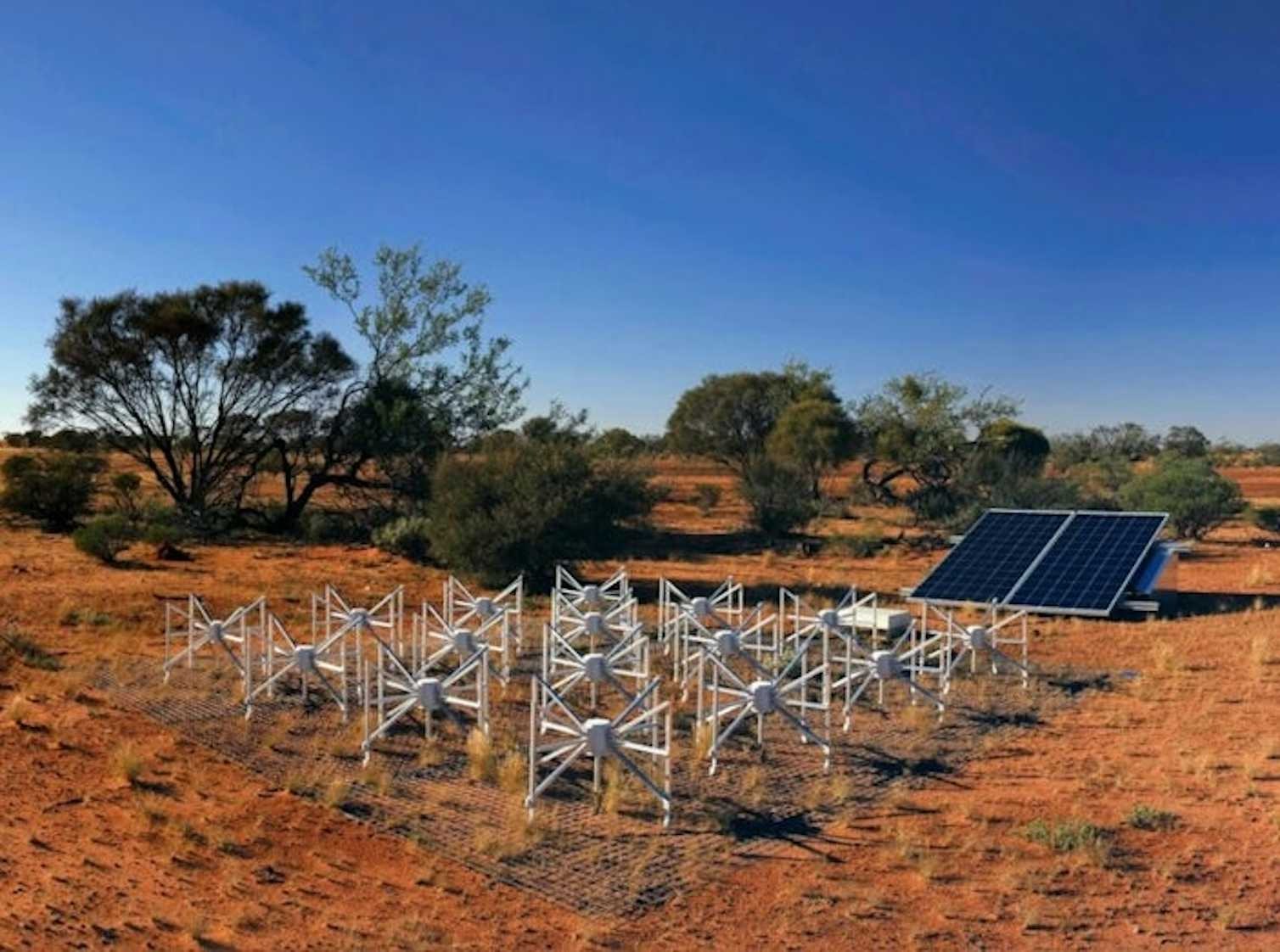

So, we started a campaign to scan the skies with the Murchison Widefield Arrayradio telescope in Western Australia, which can observe 1,000 square degrees of the sky every minute. An undergraduate student at Curtin University, Csanád Horváth, processed data covering half of the sky, looking for these elusive signals in more sparsely populated regions of the Milky Way.

And sure enough, we found a new source! Dubbed GLEAM-X J0704-37, it produces minute-long pulses of radio waves, just like other long-period radio transients. However, these pulses repeat only once every 2.9 hours, making it the slowest long-period radio transient found so far.

Where are the radio waves coming from?

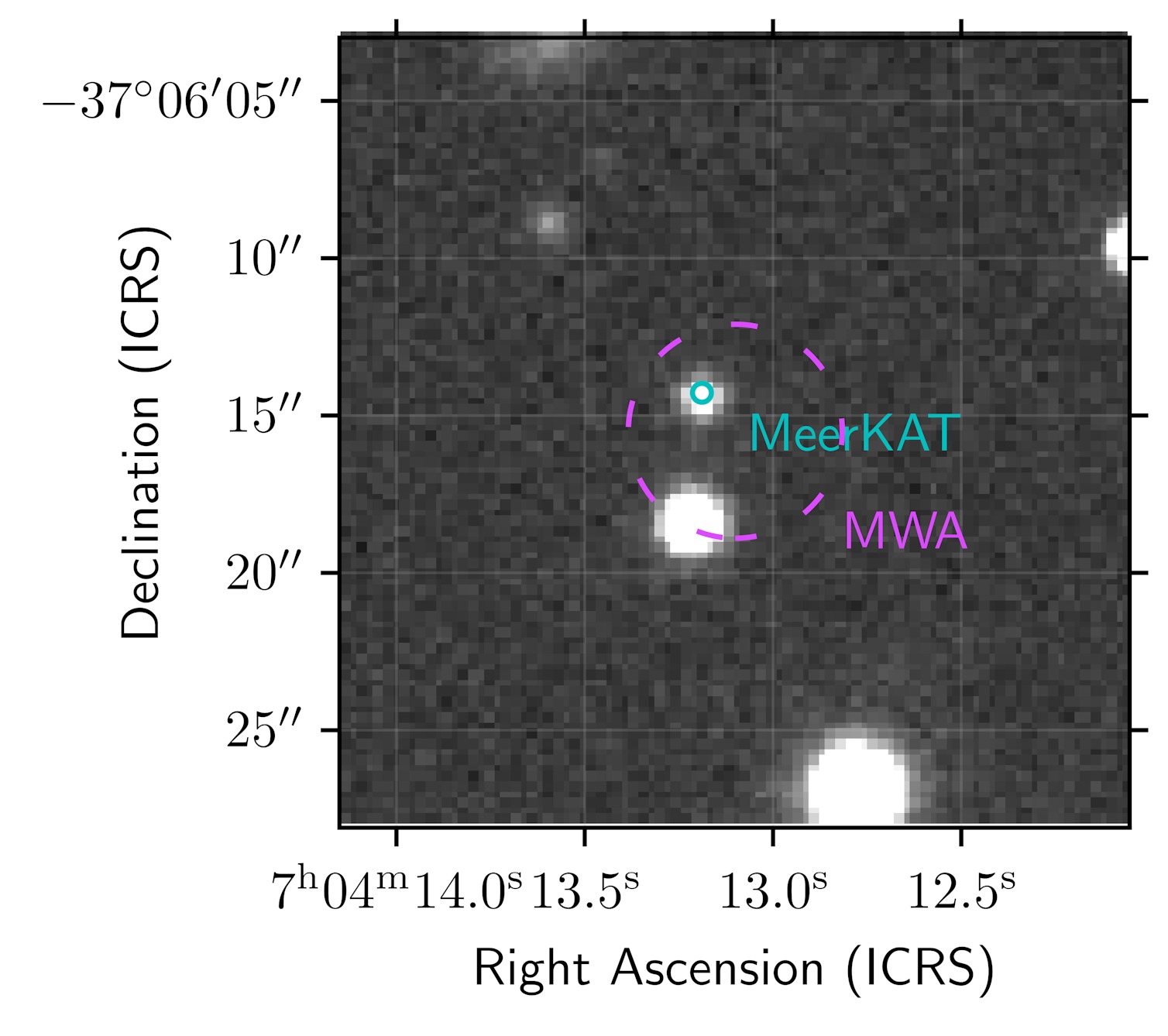

We performed follow-up observations with the MeerKAT telescope in South Africa, the most sensitive radio telescope in the southern hemisphere. These pinpointed the location of the radio waves precisely: they were coming from a red dwarf star. These stars are incredibly common, making up 70% of the stars in the Milky Way, but they are so faint that not a single one is visible to the naked eye.

It takes two to tango

So how do a red dwarf and a white dwarf generate a radio signal?

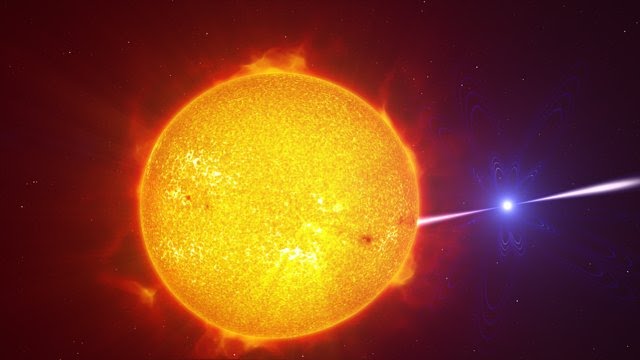

The red dwarf probably produces a stellar wind of charged particles, just like our Sun does. When the wind hits the white dwarf’s magnetic field, it would be accelerated, producing radio waves.

This could be similar to how the sun's stellar wind interacts with Earth's magnetic field to produce beautiful aurora, and also low-frequency radio waves.

We already know of a few systems like this, such as AR Scorpii, where variations in the brightness of the red dwarf imply that the companion white dwarf is hitting it with a powerful beam of radio waves every two minutes. None of these systems are as bright or as slow as the long-period radio transients, but maybe as we find more examples, we will work out a unifying physical model that explains all of them.

On the other hand, there may be many different kinds of system that can produce long-period radio pulsations.

Either way, we've learned the power of expecting the unexpected – and we'll keep scanning the skies to solve this cosmic mystery.

Originally published at The Conversation.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

I am a Senior Lecturer and ARC Future Fellow at the Curtin University node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research. I received my PhD in Radio Astronomy from the University of Cambridge in 2010 and have led several large-area radio sky surveys with the Murchison Widefield Array, exploring a wide range of science topics including supernova remnants, galaxy clusters, radio galaxy life cycles, and transient astronomy. I have won several awards, being named a WA Tall Poppies Scientist of the Year (2017), ABC Top 5 Scientist (2018), and Superstar of STEM (2019-2021).

-

Unclear Engineer From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_dwarf :Reply

"Because the material in a white dwarf no longer undergoes fusion reactions, it lacks a heat source to support it against gravitational collapse. Instead, it is supported only by electron degeneracy pressure, causing it to be extremely dense. The physics of degeneracy yields a maximum mass for a non-rotating white dwarf, the Chandrasekhar limit— approximately 1.44 times M☉— beyond which electron degeneracy pressure cannot support it. A carbon–oxygen white dwarf which approaches this limit, typically by mass transfer from a companion star, may explode as a Type Ia supernova via a process known as carbon detonation; SN 1006 is a likely example."

But, that is apparently not the case for all white dwarfs:

"White dwarfs are thought to be the final evolutionary state of stars whose mass is not high enough to become a neutron star or black hole. This includes over 97% of the stars in the Milky Way.: §1 After the hydrogen-fusing period of a main-sequence star of low or intermediate mass ends, such a star will expand to a red giant and fuse helium to carbon and oxygen in its core by the triple-alpha process. If a red giant has insufficient mass to generate the core temperatures required to fuse carbon (around 109 K), an inert mass of carbon and oxygen will build up at its center. After such a star sheds its outer layers and forms a planetary nebula, it will leave behind a core, which is the remnant white dwarf."