Gaia space telescope discovers 55 'runaway' stars careening away from stellar cluster at 80 times the speed of sound

"Discovering something new is always a thrill for a scientist."

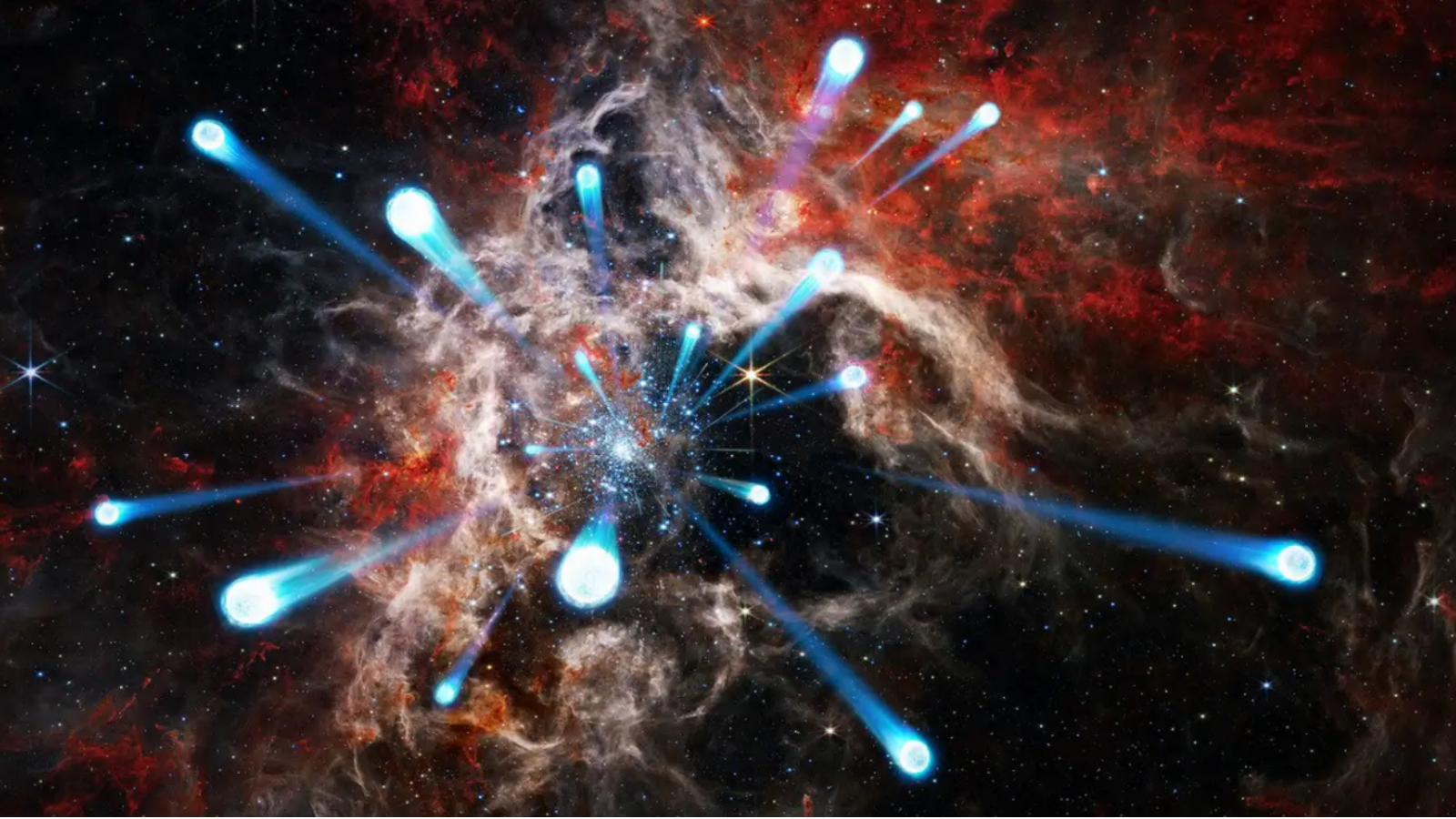

Using Europe's Gaia space telescope, astronomers have identified 55 runaway stars being ejected at high speeds from a densely packed young cluster in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), a satellite galaxy of our own Milky Way. This is the first time so many stars have been seen escaping from a single star cluster.

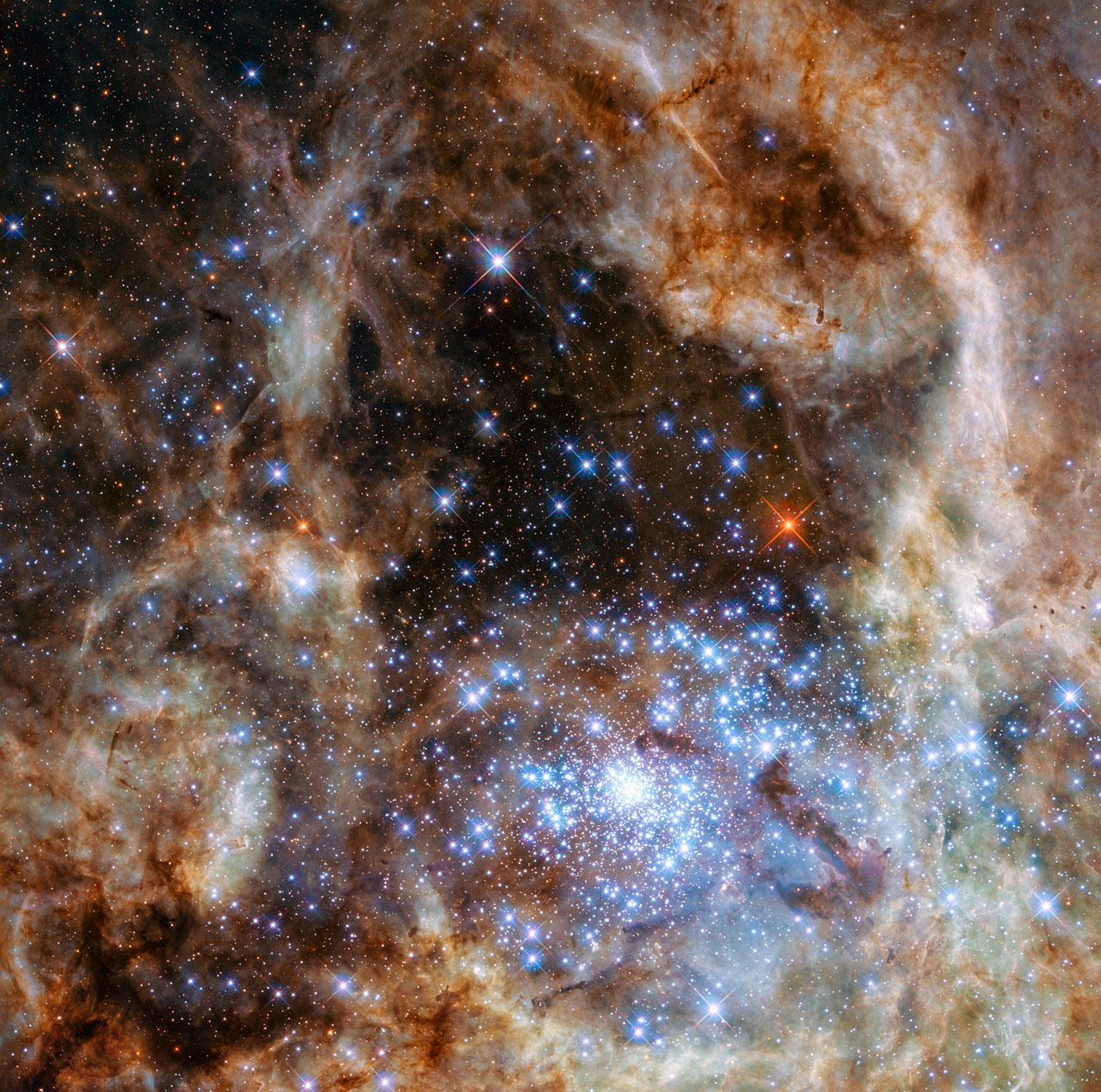

The star cluster R136, located around 158,000 light-years away, is home to hundreds of thousands of stars and sits in a massive region of intense star formation in the LMC. It's home to some of the biggest stars ever seen by astronomers, some with 300 times the mass of the sun.

The runaway stars were ejected in two bursts over the last two million years. Some of them are racing away from their homes at over 62,000 mph (100,000 kph) — about 80 times as fast as the speed of sound on Earth. The runaways massive enough to die in supernovas, leaving behind black holes or neutron stars, will behave like cosmic missiles, exploding up to 1,000 light-years from their origin point.

The discovery was made by a team of astronomers led by University of Amsterdam researcher Mitchel Stoop using Gaia, which precisely monitors the positions of billions of stars. The findings increase the number of known runaway stars by a factor of 10.

Related: Runaway 'failed star' races through the cosmos at 1.2 million mph

Scientists think that stars are exiled from young star clusters like R136 — which is estimated to be less than 2 million years old (that may seem ancient, but compare it to our 4.6 billion-year-old solar system) — when crowded stellar newborns cross paths and cause orbits to be gravitationally disrupted. What surprised the team, however, was the revelation that more than one major escape event had happened in R136, and the second one happened quite recently (in cosmic terms, at least).

"The first episode was 1.8 million years ago, when the cluster formed, and fits with the ejection of stars during the formation of the cluster," Stoop said in a statement. "The second episode was only 200,000 years ago and had very different characteristics.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"For example, the runaway stars of this second episode move more slowly and are not shot away in random directions as in the first episode, but in a preferred direction."

It is thought that these two episodes have resulted in R136 launching away as many as a third of its most massive stars in the last few million years.

"We think that the second episode of shooting away stars was due to the interaction of R136 with another nearby cluster that was only discovered in 2012," team member and University of Amsterdam researcher Alex de Koter said in the statement. "The second episode may foretell that the two clusters will mix and merge in the near future."

Massive stars like those ejected by this young star cluster can be millions of times brighter than the sun, emitting much of their energy as intense ultraviolet light. But this power comes at a cost: Massive stars like these burn through their fuel for nuclear fusion rapidly.

That means that, whereas our sun will live for around 10 billion years, the lives of massive stars will come to an end after just millions of years. The sun will end its life in a whimper, fading away as a cooling stellar remnant called a white dwarf, but these massive stars go out with a bang, erupting in supernova explosions.

Prima donna stellar cluster is losing its star power

R136 isn't just special because of its vast population of massive stars; it is the "prima donna" cluster of the largest star-birthing region of space located with five million light-years of Earth.

"Now that we have discovered that a third of the massive stars are ejected from their birth regions early in their lives, and that they exert their influence beyond those regions, the impact of massive stars on the structure and evolution of galaxies is probably much larger than previously thought," team member and University of Amsterdam researcher Lex Kaper said in the same statement. "It is even possible that runaway stars formed in the early universe made an important contribution to the so-called re-ionization of the universe caused by ultraviolet light."

The re-ionization of the universe refers to a vital phase in cosmic evolution that occurred when the now 13.8-billion-year-old universe was an infant, around one billion years old. At this time, light from early stars created bubbles of ionized gas in interstellar material. These ionized bubbles grew in lockstep with early galaxies, reionizing all hydrogen by separating electrons from hydrogen nuclei. This marked the transition from the Cosmic Dawn period to a "mature" cosmic stage that allowed for the evolution of "normal" galaxies.

The main aim of the team's research was to test the capabilities of Gaia, a European Space Agency mission that's tasked with collecting data to build a 3D map of the Milky Way. The LMC provides a good test because it is much farther away than the stars Gaia usually studies within our home galaxy.

"R136 has only just formed, 1.8 million years ago, and so the runaway stars could not yet be so far away that it becomes impossible to identify them," De Koter concluded. "If you can find a lot of those stars, you can make reliable statistical statements. This worked out beyond expectations, and we are tremendously pleased with the results. Discovering something new is always a thrill for a scientist."

The team's research was published Oct. 9 in the journal Nature.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

billslugg Be careful when simplifying for the new folks. There is no air in space. Thus no sound. They will get confused. Kilometers per second is better.Reply -

Unclear Engineer Be even more careful - the "speed of sound "WHERE?Reply

In space, there is only about 1 atom per cubic centimeter, so the mean free path to the collision with another atom is huge, and that distance is the minimum wavelength a "sound" can have, so an extremely low frequency.

But, how fast is that frequency transmitted? Based on temperature of about 6000K, the speed of sound would be about 19,000 mph. But, if it is plasma instead of neutral atoms, than it is more complicated. The speed of sound in the "solar wind" has been estimated at about 125,000 mph. See https://physics.stackexchange.com/questions/162184/what-is-the-speed-of-sound-in-space for a rather confusing discussion.

But, what the non-scientist writers of articles like this seem to be comparing to is the speed of sound in Earth's atmosphere at sea level and "standard conditions", which is 761 mph.

However, the "mach number" is really the speed at a particular location divided by the speed of sound at that location. So, saying that an airplane at 60,000 ft altitude is doing "mach 1" would mean that it is only going 660 mph, because it is colder there and the speed of sound is very dependent on the temperature in a gas.

So, please "science writers", just give us the actual speeds of whatever you are writing about, because you would have to go to a lot of work to even calculate the proper mach numbers for the situations you are writing about, and if you don't tell us what the speed of sound that you are using is, we can't tell within a factor of 1000 what you are saying. Unless we just assume you mean 761 mph whenever you say "the speed of sound". -

Torbjorn Larsson Seems it could help with ionization, since early galaxies barely produced enough escaping photons.Reply

There are sound wave analogs in the densest molecular clouds, albeit inaudible even if you removed your spacesuit and irrelevant to compare speeds.billslugg said:Be careful when simplifying for the new folks. There is no air in space. Thus no sound. They will get confused. MPH is probably better.

For an international public kilometer per second would be more reasonable, since we could compare with astronomical speeds. E.g. planets orbit stars with typical speeds of tens of kilometers per second, stars orbit galaxies with typical speeds in the low hundreds of kilometers per second and galaxies move in relation to each other with typical speeds in the high hundreds of kilometers per second.

Ejected at around 20 -30 km/s is typical relative speeds for stars, I would think. -

billslugg "For an international public kilometer per second would be more reasonable, since we could compare with astronomical speeds." = Torbjorn LarssonReply

Duly noted and corrected. -

Classical Motion If those system velocity ratios have merit, then wouldn’t the galactic velocity give us the cosmic dipole?Reply