Best Time to Observe the Moon This Month Is Now

The moon is a reliable skywatching target for many amateur astronomers and now is one of most optimum times to take a look at Earth's lunar neighbor.

The moon will be at first quarter on Sunday (April 1). This means that it will be a quarter of the way around its monthly orbit and exactly halfway between new moon on March 22 and full moon on April 6.

The days on either side of first quarter phase of the moon are the best in the month for lunar observers. That's because the sunlight is coming directly from the right, casting long shadows which emphasize the lunar landscape. The rising sun casts the moon's topography in high relief.

Some of the moon's features are familiar from Earth: mountains, plains, and valleys. The similarities can be deceiving. The lunar plains were not laid down by ancient lakes or oceans, but were formed by lava flows after impacts from asteroids.

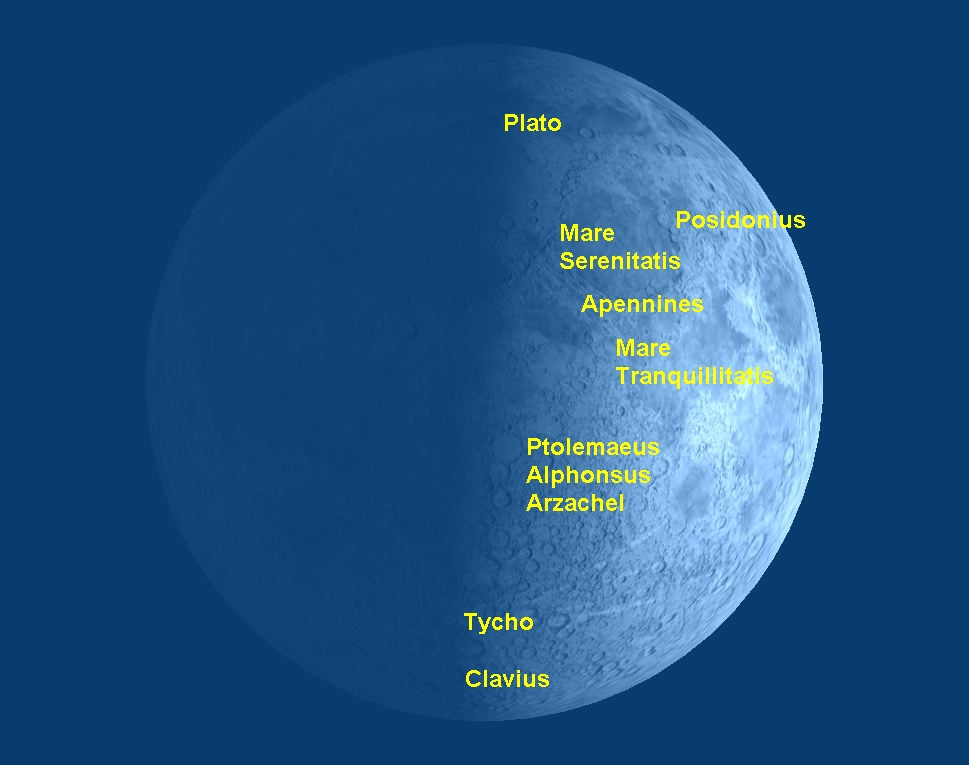

The most distinctive feature of the lunar topography is its craters. The skywatching map of the moon associated with this guide identifies many of the best lunar craters to look for during your moon-watching session.

Unlike the craters of Earth, which are mainly caused by volcanic action, the moon's craters were mostly formed by the impact of meteors and asteroids billions of years ago. Without any free water to erode them, these scars are still visible. Although there are many impact craters on Earth, nearly all have been eroded away, only detectable by geologic analysis. [How to See the Moon: Telescope Tips]

Although any small telescope will provide hours of study of the moon's surface, much of the moon's distinctive topography can be seen with binoculars or even the naked eye. Put a chair out on your deck any early evening this week, lean back, and study the moon.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The first thing you'll notice is that the moon is not symmetrical. The upper and lower halves look quite different. The top half (as seen from the northern hemisphere of Earth), consists mostly of the lunar plains called maria (singular mare), Latin for seas. They got this name from early astronomers who mistook their wide, dry, airless expanses for earthly seas. They are mostly a dark grey color.

The bottom half of the moon is lighter in color, mostly highlands covered with craters. The sunrise line is known as the lunar terminator.

Although it may not be obvious when viewed with the naked eye or binoculars, the terminator as seen through a telescope is constantly changing as the sun rises over the lunar surface. This changing pattern of sunlight and shadow is one of the most fascinating things to watch in a telescope. Put a high-power eyepiece in your telescope and study a particular crater as the sun rises over it.

The larger features of the moon are given fanciful names of mythical seas. For example, the central plain on the first quarter moon was named the Mare Tranquillitatis, Latin for the Sea of Tranquility. It was here on July 20, 1969 that Apollo 11 landed.

The mountain ranges on the moon are named after mountain ranges on Earth, such as the Apennine Mountains which divide the Mare Tranquillitatis from the larger Mare Serenitatis (Sea of Serenity) to its north.

The craters on the moon are mostly named for famous lunar scientists of the past. Nearly all are dead; the only living people with craters named after them are the Apollo astronauts. Because the ancient astronomers were mostly male, there are a series of craters carrying common female names, such as Ann, Carol, Diana, Grace, Kathleen, Louise, Mary, and Susan.

The most obvious craters around first quarter are the three large craters close to the center of the terminator: Ptolemaeus, Alphonsus, and Arzachel. In the north, Plato and Posidonius are prominent; in the south you can see Tycho and Clavius.

It's as much of a challenge to learn the names of the moon's surface features as it is to learn the names of the constellations or the brightest stars, and quite rewarding in its own way. It's a way of knowing more about our neighbor world while also honoring our predecessors in the study of the moon.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.